![]()

CHAPTER 1

Health Care and Organized Interests in the United States

Universal health care coverage was on the national political agenda for nearly a hundred years, from the platform of Teddy Roosevelt’s Bull Moose Party in 1912, to President Franklin Roosevelt’s consideration in the 1930s, to the long string of presidents who introduced major reform bills to expand access—starting with Harry Truman in the 1940s, to Lyndon Johnson, who got Medicare and Medicaid adopted in 1965; continuing with Richard Nixon, who introduced a universal coverage plan subsequently endorsed by Gerald Ford; and to Bill Clinton, whose universal coverage plan based on managed competition failed in 1994. None of their proposals ever reached consideration on the floor of the US Congress. Not until a comprehensive health reform bill supported by President Barack Obama reached the floor of the US House of Representatives on Christmas Eve 2009 did a universal coverage bill (or near-universal, in this case) get so far in the congressional process. Thus the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) in March 2010 was truly a landmark accomplishment. In the punctuated equilibrium framework offered by Baumgartner and Jones (1993), we observed nearly a hundred years of stability within the health policy subsystem, interrupted only by the addition of Medicaid and Medicare in the 1960s, and then finally in 2010 we had a dramatic punctuation in this equilibrium. To be sure, the federal government had made a couple of incremental adjustments that increased coverage for specific groups, namely, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which was enacted in 1997 for children, and Medicaid’s 1115 waiver program, which affects clients who meet state and federal eligibility criteria.1 But neither program purports to be a universal coverage program for all citizens.

At the point of this writing in December 2012, we do not know how the ACA will play out, given that the Republicans opposed its passage and are placing obstacles in front of its implementation. The new law passed a critical first hurdle when the individual mandate and its associated features, such as state exchanges and consumer protections/insurance regulations, were declared constitutional by the US Supreme Court in June 2012.2 However, the Medicaid expansion was changed from mandatory to a state choice, albeit a sweet one in which states receive a 100 percent match through 2019 and then 90 percent thereafter. One sign of an implementation problem was that the attorneys general of twenty-six states, all of them Republican, filed or joined lawsuits that wound up at the US Supreme Court, seeking to dismantle the individual mandate, the insurance exchanges, and the extension of Medicaid. Now these same states are being relied upon to implement the state exchanges, which most had not started planning by the late fall of 2012, and to implement the addition of many new patients onto the Medicaid rolls, to which many of them are opposed. Given the Republicans’ unified control of twenty-four state governments after the 2012 elections, they should be able to continue to pursue a policy of noncooperation at the state level, such as not participating in the exchanges and entering into Interstate Healthcare Freedom Compacts. However, the ACA’s future was secured when Barack Obama was reelected president in November 2012 and the Democrats retained control of the US Senate. At that point the ACA became the law of the land in a way that it had not been in 2010. Hopefully, it will be a true punctuation that reforms the health care system.

The States’ Record on Health Care Reform

If instead of a singular focus on what was happening or not happening in Washington during the last century, what if we look one level down—to what the states were doing in health policy? How stable were the health policy subsystems in the fifty states in contrast to the national system? Universal coverage was first adopted by the state of Hawaii in 1974; in the few years before and after the failure of the Clinton plan, the states were very active players in universal coverage: Seventeen states enacted some step toward universal coverage by 2002. In the first decade of this century Maine (2003), Vermont (2006, 2011), and Massachusetts (2006) enacted new universal coverage laws, while at the national level the “public option” proposed in 2010 did not fare so well. It lies buried in the congressional graveyard, leaving some 23 million people without health care access under the 2010 law (Oberlander 2010, 1116). And in 2011 Vermont made history by creating the nation’s first “single-payer” health system, Green Mountain Care, to be implemented in 2013 once funding is identified. Thus, the states’ record on providing and attempting to provide universal care during the past forty years merits scholarly attention, as least as much as the national government’s failure until 2010 has captivated scholars’ imagination.

During the same forty-year period the rise and fall of managed care has been one of the most important health care developments in the United States. By the 1990s a backlash against stricter forms of managed care had set in across the country. Congress repeatedly failed to produce any broad patient protection legislation, aside from the 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), while all fifty states were active in the regulation of managed care and in offering other ways to protect patients. These state laws, enacted in a backlash against managed care organizations, included new rights for consumers, such as the right to sue, and new limitations on providers and health plans. Legislation in this area diffused quickly across the states in the middle to late 1990s, in what appeared to be a bandwagon effect.

In a third important area of state activity, thirty-four states provided their low-income seniors with financial assistance for their prescription drug bills before the federal government could manage to add that benefit to Medicare, partially in 2003 under President George W. Bush, and fully by 2020 under the ACA. These pharmaceutical programs are of a more routine nature, less conflictual than “whipping HMOs [health maintenance organizations] into shape” and less costly than offering health care to all citizens; yet they are welfare programs, and as such should be expected to generate some opposition. Thus, in contrast to the national level, the state-level health policy subsystem does not appear to be in equilibrium, at least not in the past forty years. Rather, this quick summary of the three health reforms we study in the chapters that follow suggests many punctuations by universal coverage enactments, HMO regulations, and the provision of financial assistance to low-income seniors for prescription drug coverage. Thus studying policymaking activities at the state level, as we do in this book, is likely to be far more illuminating about the role of health interests than studying them at the national level, where basically little but gridlock happened, especially with regard to universal coverage, for one hundred years.

Ours is not necessarily a popular position, given that analysis of nonevents at the national level (e.g., “why no national health insurance?”) has consumed the bulk of scholarly attention to health reform, in contrast to relatively sparse research at the state level. Research on state health reform in fact exists only in scholarly journals and in edited books published in the 1990s, with Hackey and Rochefort’s 2001 edited volume on reforms in state health policy being the most recent one. To the best of our knowledge, this book is the first scholarly examination of state health reforms from a political science perspective in more than twenty years. Thus, here we are necessarily plowing new ground.

Why National Health Care Reform Now?

It is of course also intriguing to analyze why a policy punctuation in the form of the ACA did occur at the national level in 2010, especially because it will be carried out by the states. Although the scholarly analysis of the enactment of the ACA is far from complete, no doubt much of it will center on the differences between Clinton’s failure and Obama’s success in achieving major reform.

Before 2010, the canonical story about the lack of health care policy reform was about an undersized David of public interest waging an uphill struggle against the Goliath of big interests. This story is a standard explanation for the failure of Clinton’s plan in 1994. Scholars such as Jamieson (1994), West, Heith, and Goodwin (1996), West and Loomis (1999), Weissert and Weissert (2002), and Quadagno (2005), and journalists such as Johnson and Broder (1996), assigned primary blame for the 1994 fiasco to powerful interests representing the health care industry. So scholars with an interest group lens will presumably look toward changes in interest group composition between 1994 and 2010 or to Obama’s strategy in dealing with organized interests as possible reasons for the passage of reform in 2010. Even scholars identifying other culprits—the president’s strategy somehow “boomeranged” (Skocpol 1996) or “It’s the institutions, stupid!” (Steinmo and Watts 1995), policy feedback limits the United States to only incremental reforms (Mayes 2004), or ideology and the sheer complexity of the institutions of the American health care industry (Starr 2011)—agreed that one consequence of their preferred culprit’s culpability was to yield enormous power to intransigent organized interests.

Still other scholars (e.g., Peterson 1995; Baumgartner and Talbert 1995) focused more specifically on the internal structure of Congress as the reason for the demise of the Clinton plan; they argued that fragmentation of jurisdictional control over health policy in Congress set up a situation whereby special interests could become more entrenched. Interestingly, one set of congressional scholars (Brady and Kessler 2010) predicted during the height of the reform debate (in a piece published in April 2010) that the outcome for Obama would likely be the same as for Clinton—defeat. They used gridlock theory to show that the Clinton proposal was far to the left of the median House member or the pivotal Senate member, thereby dooming it to failure in 1994. They then showed that the basic conditions remained the same in 2010: Public opinion was about the same as in 1994; the party lineup in each chamber of Congress was almost exactly the same in 2010 as in 1994 and hence the gridlock regions remained the same; but the economy was in much worse shape in 2010 than in 1994 (Brady and Kessler 2010). Such a pessimistic analysis so late in the legislative game just underscores how skillful President Obama and Democratic legislative leaders were in accomplishing this victory.

In early analyses of the ACA’s passage, scholars have continued the theme of analyzing organized interests and institutions, but they often credit President Obama with more skillfully managing negotiations among competing interests and in shepherding legislation through institutions with many veto points. Lawrence Jacobs (2010), for example, stresses the importance of the deals that the president and Democratic leaders cut with medical providers, medical manufacturing groups, and pharmaceutical manufacturers in exchange for their vocal support or silence on the bill, a view echoed by Quadagno (2011), Brown (2011), and Hacker (2011). Jacobs and Skocpol (2010) say that some of these stakeholder groups even contributed to advertising campaigns promoting reform; conversely, they argue that Obama never had to suffer all-out unified opposition from the business community.3 Peterson (2011) rates both the interest group and institutional prospects as more auspicious for President Obama than for any other president since Franklin Roosevelt, but he also lauds Obama’s leadership in exploiting the opportunity. Overall, the triumph over or accommodation to health industry interests (Gibson and Singh 2012) as a compelling reason for the ACA’s passage seems to be a central theme in the scholarly analysis of the reform’s enactment.

Relatively less emphasis is placed on institutional features as a factor in the bill’s passage, but institutional constraints, such as the presence of the filibuster in the Senate, shaped the bill’s final content, eliminating the public option and substituting state insurance exchanges for a national exchange (Hacker 2010). Other institutional scholars credited the more centralized and partisan legislative process, called “unorthodox lawmaking,” that congressional Democrats borrowed from the Republicans, for the Democrats’ victory on health care reform (Beaussier 2012). Still others saw the ACA as just the latest example of delegated governance in which there is only a limited increase in federal governing authority, while most responsibility for the administration and delivery of social programs is shifted away from the federal level to private agents or subnational governments (Morgan and Campbell 2011a). Delegation is seen as a way to overcome institutional barriers to reform.

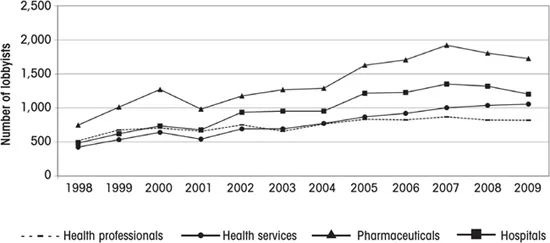

Figure 1.1 Lobbyists by Health Subsector, 1998–2009

Source: Calculated by the authors from data at opensecrets.org.

Health Care Interests in Washington

From this quick survey of the literatures on both President Clinton’s failure and President Obama’s success, it is evident that the interest-based approach taken in this book on the states is compatible with one at the national level. It is clear that health interests, once mobilized for the 1994 battle, stayed in Washington, resulting in partisan gridlock over patient protection legislation and Medicare prescription drug benefits for the next decade. Figure 1.1 shows this trend. The number of health industry lobbyists registered to lobby on all health issues totaled 790 in 1998, with all four health industries relatively equal in numbers. There was an inflection point in 2004, when the number of groups increased until 2007 for hospitals and pharmacies. Health services, conversely, increased in a steadily linear fashion through 2009, whereas health professions were more stable across the twelve-year period.4 Reported lobbying expenditures by health industry groups for the 1998–2010 period totaled nearly $4 billion (Center for Responsive Politics data reported by Hacker 2010, 865).

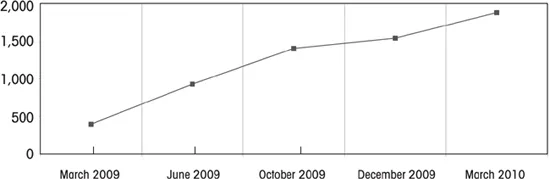

Lobbying on the ACA was the most intense phase of this period. As seen in figure 1.2, which displays all types of organizations lobbying, not just health groups, 1,880 organizations were registered to lobby on health care reform by the final weeks of the debate in Washington—a nearly fivefold increase from the previous year. Many groups outside health care lobbied, especially business groups such as the US Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Realtors, and individual corporations, as well as welfare and human rights advocacy groups, and tribal nations. In 2009 the health care industry spent more than $500 million on lobbying, while the Chamber of Commerce spent $144 million (Hacker 2010, 865, 873).

Figure 1.2 Federal Lobby Registrations for Health Reform, 2009–10

Note: These data come from the Center for Responsive Politics. Rather than listing the groups that lobby on a specific bill, CRP has also listed groups registered to lobby by keyword, such as “healthcare reform,” or by bill number and bill title. The key words used to create the search for the first quarter of 2010 were: HR 3200, S. 1796, HR 3962, HR 3590, “affordable health,” “healthy future,” “health care for America,” “health insurance reform,” “healthcare reform,” “health care reform,” and “patient protection” and “Affordable care.” They were obtained from Michael Beckel, author of the article found at www.opensecrets.org/news/2010/03/number-of-special-interest-groups-v.html. The other four quarters were obtained from this article.

Source: Calculated by the authors.

The Research Puzzle of This Book

The adoption of health policy reform legislation at the state level has been relatively successful compared with the national level, where comprehensive reform had often failed until adoption of the ACA in March 2010. Policy changes in many states in at least three important areas of health policy—universal coverage, regulation of managed care, and financial assistance to seniors for prescription drugs—kept reformers’ hopes alive. Although organized interests have been blamed for blocking reform in Washington for nearly one hundred years, the same interests exist in the fifty state capitals, where successful reforms have nonetheless been achieved. This is the central research puzzle of this book.

The fact that state governments took action on health policy in spite of opposing interest forces where the national government did not offers a compelling puzzle that could be studied in a variety of ways. Our approach is to try to understand why the states took action at all and to capitalize on the variation among states in reforms attempted and achieved. The fact that some states took action while others did not offers us variation and affords us the opportunity to test explanations about why some legislatures tackle policy problems and others do not. In particular, we can leverage the institutional variation of the fifty state legislatures and the variation of fifty state interest group systems in our analyses. Further, because states responded with different levels of regulatory stringency and generosity of benefits, we also have the opportunity to test explanations of these dimensions. These are not investigative opportunities that scholars have available at the national level where they are faced with a sample size of one. With the variation provided by the states, we are able to take some of the major explanations for reform failures, such as opposition by organized interests and institutional gridlock, and test them systematically at the state level—something that scholars of national reform are not able to do.

In this chapter we introduce the major state-level health care reforms that we study in this volume—pharmacy assistance, managed care regulation, and universal coverage. Analysis of these three policy areas is the focus of chapters 3, 4, and 5, in which we compare the states’ successes with the federal government’s lack of success or slowness to succeed. We also outline how the 2010 federal law enacted by Congress and upheld by the Supreme Court will affect the states and how the states’ capacities in turn will ...