![]()

1

Discourse in Web 2.0: Familiar, Reconfigured, and Emergent

SUSAN C. HERRING

Indiana University Bloomington

Introduction

FROM CONTROVERSIAL BEGINNINGS, the term Web 2.0 has become associated with a fairly well-defined set of popular web-based platforms characterized by social interaction and user-generated content. Most of the content on such sites is human discourse, via text, audio, video, and static images. It is therefore, in principle, of theoretical and practical interest to scholars of computer-mediated discourse. Yet although discourse-focused studies of individual Web 2.0 environments such as Facebook, Flickr, Twitter, and YouTube are starting to appear (see, for example, the chapters in Thurlow and Mroczek 2011), systematic consideration of the implications of Web 2.0 for computer-mediated discourse analysis (CMDA) as a whole is lacking. Does discourse in these new environments call for new methods of analysis? New classificatory apparatuses? New theoretical understandings? In this chapter I attempt to address these questions.

After defining Web 2.0 and reviewing its development over the past decade, the CMDA paradigm developed by the author (Herring 2004) is briefly reviewed, with the ultimate goal of determining whether—and if so, in what ways—it needs to be revised in light of Web 2.0. As a heuristic to address this goal, I introduce a three-part classification of Web 2.0 discourse phenomena: phenomena familiar from older computer-mediated discourse (CMD) modes such as email, chat, and discussion forums that appear to carry over into Web 2.0 environments with minimal differences; CMD phenomena that adapt to and are reconfigured by Web 2.0 environments; and new or emergent phenomena that did not exist—or if they did exist, did not rise to the level of public awareness—prior to the era of Web 2.0. This classification is loosely inspired by Crowston and Williams’s (2000) broad classification of web pages into “reproduced” versus “emergent” genres, but with a focus on discourse, rather than genre.

I suggest that this three-way classification can provide insight into why particular discourse phenomena persist, adapt, or arise anew in technologically mediated environments over time. In so doing, I invoke technological factors such as multimodality and media convergence, social factors at both the situational and cultural levels, and inherent differences among linguistic phenomena that make them variably sensitive to technological and social effects. Suggestions are also made of practical ways in which the classification might guide researchers to frame their studies and select certain methods of analysis. While the reconfigured and emergent categories are especially attractive in that they present new phenomena and raise special challenges for analysts of CMD, I argue that researchers should not neglect what appears familiar in favor of pursuing newness or novelty: all three categories merit research attention, for different reasons.

Background

The World Wide Web itself is not new. It was pitched as a concept by physicist Tim Berners-Lee to his employers at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) in 1990, implemented by 1991, and attracted widespread attention after the first graphical browser, Mosaic, was launched in 1993.1 The early websites of the mid-1990s tended to be single-authored, fairly static documents; they included personal homepages, lists of frequently asked questions (FAQs), and ecommerce sites. The late 1990s saw a shift toward more dynamic, interactive websites, however: notably blogs (Herring et al. 2004) and online newssites (Kutz and Herring 2005), the content of which could be—and often was—updated frequently and which allowed users to leave comments on the site. These sites foreshadowed what later came to be called Web 2.0.

What Is Web 2.0?

The term “Web 2.0” was first used in 2004 when Tim O’Reilly, a web entrepreneur in California, decided to call a conference he was organizing for “leaders of the Internet Economy [to] gather to debate and determine business strategy” the “Web 2.0 Conference” (Battelle and O’Reilly 2010; O’Reilly 2005). At the time, the meaning of the term was vague—more aspirational and inspirational than descriptive. As a business strategy, Web 2.0 was supposed to involve viral marketing rather than advertising and a focus on services over products. One of O’Reilly’s mantras is “Applications get better the more people use them” (Linden 2006). Today the term refers, according to Wikipedia (2011b) and other online sources, to changing trends in, and new uses of, web technology and web design, especially involving participatory information sharing; user-generated content; an ethic of collaboration; and use of the web as a social platform. The term may also refer to the types of sites that manifest these uses, such as blogs, wikis, social network sites, and media-sharing sites.

From the outset, the notion of Web 2.0 was controversial. Critics claimed that it was just a marketing buzzword, or perhaps a meme—an idea that is passed electronically from one internet user to another—rather than a true revolution in web content and use as its proponents claimed. They questioned whether the web was qualitatively different in recent years than it had been before, and whether the applications grouped under the label Web 2.0—including such diverse phenomena as online auction sites, photosharing sites, collaboratively authored encyclopedias, social bookmarking sites, news aggregators, and microblogs—formed a coherent set. Tim Berners-Lee’s answer to these questions was no—for the inventor of the web, the term suffered from excessive hype and lack of definition (Anderson 2006).

Table 1.1 Web 2.0 vs. Web 1.0 phenomena (adapted from O’Reilly 2005)

Web 1.0 | Web 2.0 |

Personal websites | Blogging |

Publishing | Participation |

Britannica Online | Wikipedia |

Content-management systems | Wikis |

Stickiness | Syndication |

Directories (taxonomies) | Tagging (folksonomies) |

In response to such criticisms, O’Reilly (2005) provided a chart to illustrate the differences between Web 2.0 and what he retroactively labeled “Web 1.0.” This is shown in modified and simplified form in table 1.1. The phenomena in the second column are intended to be the Web 2.0 analogs of the phenomena in the first column.

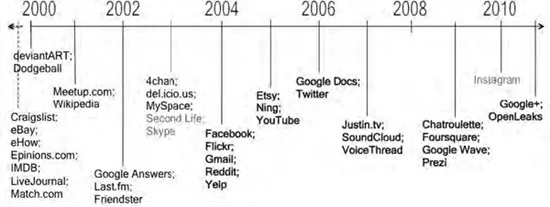

This is no more than a list, however; it does not provide a principled way to determine what should or should not be included as “Web 2.0.” An alternative approach to conceptualizing Web 2.0 is from a temporal perspective. Most Web 2.0 phenomena emerged over the last decade; indeed, one criticism of the concept is that it seems to mean nothing more than “recent websites”—paving the way for “Web 3.0,” Web 4.0,” etc., to describe ever-newer web-based phenomena in the future. Figure 1.1 situates phenomena that exhibit characteristics of “Web 2.0” along a timeline for roughly the first decade of the twenty-first century. The phenomena included in the figure are not intended to be exhaustive in any sense; however, an attempt has been made to include important exemplars of a range of phenomena. In the figure, applications that run on a platform other than the web but otherwise have characteristics of Web 2.0 are indicated in lighter text; Web 2.0 sites that were launched before O’Reilly coined the term in 2004 are indicated in black type; and Web 2.0 sites launched since 2004 are in bold type.2

Figure 1.1 Web 2.0 timeline (selective).

The most recent decade of collaborative communicative technologies is not a perfect match with Web 2.0 in the strict sense. Not all of the applications mentioned in figure 1.1 are based in the web—for example, Second Life (a three-dimensional graphical world) and Skype (a form of internet telephony) are applications that run on the internet but not on the web, and Instagram, a recently introduced photosharing application, runs on mobile phones (although it can share with web-based social network sites). Moreover, a number of sites commonly considered to be Web 2.0 were launched before 2004, and some—such as eBay, blog-hosting sites (such as LiveJournal), and online dating sites—go back to the 1990s. Nonetheless, with these exceptions, and together with the characteristics of the sites themselves, the timeline suggests some conceptual coherence that can be attributed to these phenomena. Thus, for the purpose of this chapter, the following redefinition of Web 2.0 is proposed: web-based platforms that emerged as popular in the first decade of the twenty-first century, and that incorporate user-generated content and social interaction, often alongside or in response to structures or (multimedia) content provided by the sites themselves.

Computer-Mediated Discourse Analysis, Media Convergence, and “Discourse 2.0”

The second key background component of this chapter is discourse analysis and, specifically, the approach to analyzing online discourse that I have developed over the past seventeen years, CMDA. CMDA is an approach to the analysis of computer-mediated communication (CMC) focused on language and language use; it is also a set of methods (a toolkit) grounded in linguistic discourse analysis for mining networked communication for patterns of structure and meaning, broadly construed (Herring 2004).3

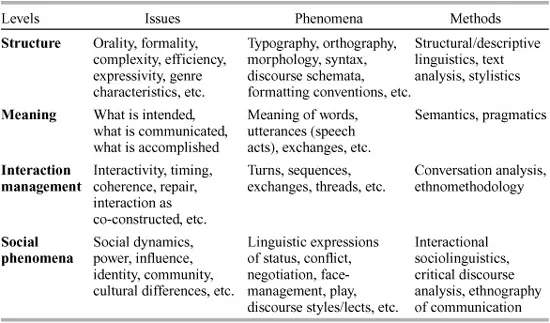

The term “computer-mediated discourse analysis” was first used as the name of a GURT workshop I organized in 1994. Since then it has evolved into a model organized around four levels of CMDA: structure, meaning, interaction management, and social phenomena (Herring 2004). The organizational principle of the CMDA toolkit is fairly simple: The basic idea is to adapt existing methods, primarily from linguistics (but in principle from any relevant discipline that analyzes discourse), to the properties of digital communication media. The methods and the phenomena, along with broader issues they address, are then loosely mapped onto four levels of hierarchy, from the microlinguistic, more context-independent level of structure to the macrolevel of contextualized social phenomena, as summarized in table 1.2. (A nonlinguistic level—participation—is sometimes included as well.)

However, in the time since the CMDA approach was originally conceptualized, CMC itself has been undergoing a shift, from occurrence in stand-alone clients such as emailers and instant messaging programs to juxtaposition with other content, often of an information or entertainment nature, in converged media platforms, where it is typically secondary, by design, to other information or entertainment-related activities (Herring 2009; Zelenkauskaite and Herring 2008). This phenomenon, which I refer to as convergent media computer-mediated communication (CMCMC), is especially common on Web 2.0 sites. Examples include text comments on photosharing sites; text (and video) responses to YouTube videos; text (and voice) chat during multiplayer online games; and text messages from mobile phones posted to interactive TV programs. Less prototypically (because it involves the convergence of text with text rather than the convergence of text with another mode), CMCMC is also illustrated by reader comments on news stories; “talk” pages associated with Wikipedia articles; status updates and comments (and for that matter, chat and inbox exchanges) on Facebook profiles; and interpersonal and group exchanges on Twitter.4

Table 1.2 Four levels of CMDA (adapted from Herring 2004)

In fact, the overlap between CMCMC and Web 2.0 is considerable. Almost all so-called Web 2.0 sites feature CMCMC, and almost all CMCMC applications are on the web. An exception to the former is social bookmarking sites such as del.icio.us, which do not contain CMC; an exception to the latter is text chat in multiplayer online games such as World of Warcraft, which are not hosted on the web. However, the trend is for increasing convergence, and it would not be surprising if these distinctions disappeared in the future. In what follows, it is assumed that Web 2.0 generally involves CMCMC.

The discourse in these new environments—what we might call convergent media computer-mediated discourse (CMCMD) or Discourse 2.0—raises many issues for CMDA. There are new types of content to be analyzed: status updates, text annotations on video, tags on social bookmarking sites, and edits on wikis. New contexts must also be considered—for example, social network sites based on geographic location—as well as new (mass media) audiences, including in other languages and cultures. (Facebook, for example, now exists in localized versions in well over one hundred languages [Lenihan 2011].) Discourse 2.0 manifests new usage patterns, as well, such as media coactivity, or near-simultaneous multiple activities on a single platform (Herring et al. 2009) and multiauthorship, or joint discourse production (Androutsopoulos 2011; Nishimura 2011). The above reflect, in part, new affordances made available by new communication technologies: text chat in multiplayer online games (MOGs); collaboratively editable environments such as wikis; friending and friend circles on social network sites; social tagging and recommender systems; and so forth. Last but not least, Discourse 2.0 includes user adaptations to circumvent the constraints of Web 2.0 environments, such as interactive uses of @ and #, as well as retweeting, on Twitter (boyd, Golder, and Lotan 2010; Honeycutt and Herring 2009) and performed interactivity on what are, in essence, monologic blogs (Peterson 2011; Puschmann 2013). Each of these issues deserves attention, and some are starting to be addressed, but on a case-by-case, rather than a systemic, basis.

In the face of so many apparently new phenomena, one might question whether Discourse 2.0 should continue to be called CMD. The term “computer-mediated” originally referenced the term “computer-mediated communication,” which is still preferred by communication scholars. But communication technologies are increasingly moving beyond computers. Mobile phones can be considered honorary computers, but voice calls, for example, chal...