THE 50 GREATEST CHURCHES AND CATHEDRALS OF GREAT BRITAIN

BATH ABBEY

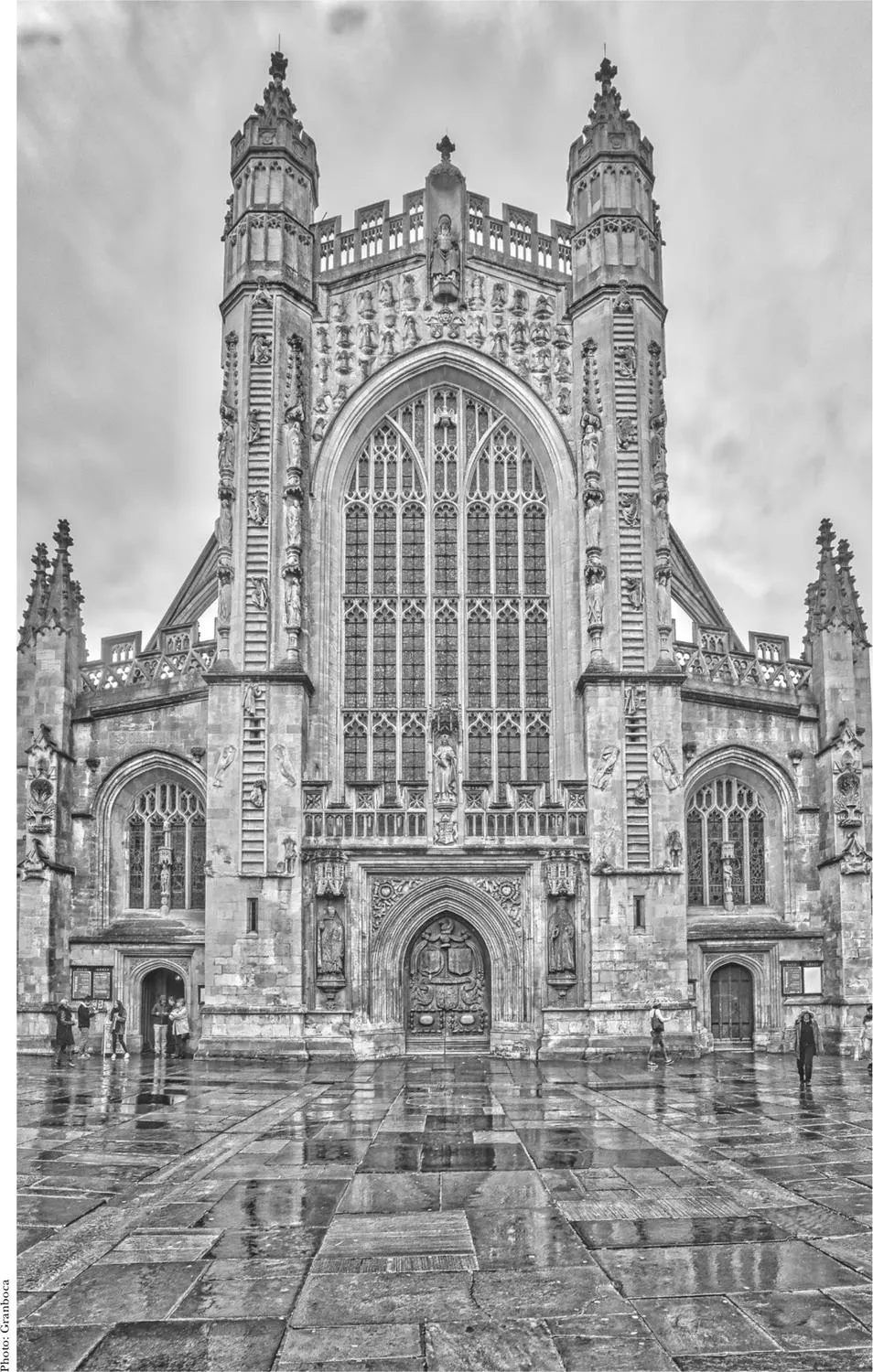

At the heart of the city’s busy shopping streets, in a piazza of cafés and milling crowds, Bath’s magnificent Abbey Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul presents a story in stone like no other. Its unique west front has angels clambering up ladders (and occasionally slipping down a rung or two) alongside columns of supporting saints and Christ sitting in Majesty between turrets at the top. A statue of King Henry VII watches over the door.

So great is the sense of beauty and unity of the architecture within, that it comes as a surprise to discover that the Abbey’s nave and aisles are actually Victorian, albeit a replica of Tudor design. The glorious fan vaulting that carries the eye the full length of the church seems all of a piece, but only the chancel vault originates from the 16th century.

The story of the Abbey goes back into the mists of time – there was even a site of worship here in pre-Christian times. Although little is known about the Benedictine Anglo-Saxon abbey, it is recorded that King Edgar the Peaceful was crowned in Bath in 973.

The form of that service, devised by St Dunstan, the then Archbishop of Canterbury, has formed the basis of all coronation services down the centuries, including that of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. This pivotal moment in history is commemorated in the Edgar Window at the end of the north aisle.

The Norman conquerors began an extensive building programme in the early 1090s. The bishopric had been at nearby Wells in 1088 when John of Tours was made Bishop of Wells. A few years later he was granted the city of Bath, the abbey and monastic buildings, and promptly set grand plans into motion.

Not only would the bishopric be moved to Bath, he would extend the monastery, build a bishop’s palace and replace the Saxon abbey with a massive new cathedral. After his death, the work continued under Bishop Robert of Lewes, with the cathedral completed in the 1160s. It was so vast that today’s Abbey would fit into its nave.

Bath’s importance declined when the bishops made Wells their principal seat of residence during the 13th century. The monks found the upkeep of the buildings difficult and by the time of the Black Death in 1398, which decimated their numbers, it had become impossible. The great cathedral descended into decay.

When Oliver King, Bishop of Bath and Wells, arrived in 1495, tradition tells that he had a dream in which he saw angels ascending and descending ladders to heaven and heard a voice telling him to build a new church. This has since been dismissed as a marketing myth, conjured by a desperate fundraiser a century after Bishop King’s death, but building began and the angels keep their secrets on the west front.

The bishop commissioned King Henry VII’s finest master masons, Robert and William Vertue, to build in the Perpendicular Gothic style. They promised him ‘the finest vault in England’ (and went on to work at Westminster Abbey). The building was in use but not completed when Prior Holloway and fourteen monks surrendered it to King Henry VIII in 1539.

Looted, the stained glass ripped out and destroyed, the lead stripped from its roof, the shell was sold on to local gentry. In 1572 it was presented to the City Corporation and citizens of Bath for use as their parish church. The nave was given a simple roof and the east end used for services. Houses soon surrounded it and the north aisle became a public passageway.

By the early 19th century Bath Abbey was again in dire straits. Three restorations took place under the city architect but it was Charles Kemble, appointed Rector in 1859, who really came to the rescue.

He commissioned the noted Gothic Revival architect Sir George Gilbert Scott to draw up plans for a complete restoration – and funded much of it himself. Work began in 1864 and transformed the interior, resulting in the aweinspiring church we see today.

Scott looked to Bishop King’s vision and the work of the Tudor master masons, so meticulously matching the design of their fan vaulting in his nave that you have to look very carefully to see the joins. When the Abbey reopened in 1871, Scott felt he had completed the building as the medieval craftsmen had intended.

Pointed arches and flying buttresses enabled the late Perpendicular builders to maximise window areas. In Bath Abbey they occupy some 80 per cent of the wall space and the Victorian stained-glass artists and glaziers filled them well.

The great east window, which depicts 56 events in the life of Christ, from the Annunciation to the Ascension, rises to the full height of the wall and contains 818 square feet (76 square metres) of glass. Partially destroyed by air raids in 1942, it was repaired by the great grandson of the original designer.

The great west window – known as a Pentateuch Window because it tells of stories and events from the first five books of the Bible – ascends in three tiers, from the creation of Eve up to the Passover when the Israelites were delivered from slavery in Egypt.

The nave and quire aisles are lined with memorial tablets – 641 of them, only Westminster Abbey has more – and on the floors are 891 grave slabs (ledger stones) dating from 1625 to 1845. As well as recording the name and dates of the person buried there, many of these contain interesting inscriptions about the person, their family and their life in the local community.

Abbey benefactors get their place in the limelight, none more so than John Montague, Bishop of Bath and Wells in 1608, who donated a tidy sum for the nave to be roofed after the king’s commissioners had left it open to the elements. His effigy-topped table tomb is grandly placed behind iron railings between the north aisle and the nave.

In the 18th century, the north transept was where the city housed a fire engine. Now it is home to the renowned Klais Organ, installed in 1997. The delightful frieze of twelve angel musicians, carved in lime wood, was added above the quire screens ten years later.

Do take a closer look. Each angel has its own definite character and the designer, sculptor Paul Fletcher, had a sense of humour. Two violinists face each other as if playing a duet, one using her wings to shield her ears from the bagpipes next to her. Only the cellist is looking towards the conductor, and she has her eyes closed.

The 20th century saw restoration and additions and now Footprint, an ambitious £19.3 million building programme started in 2018, has been designed to bring the Abbey firmly into the 21st century.

Crucially it involves the repairing and stabilising of the floor, which is collapsing, and installing an eco-friendly heating system that utilises the energy from Bath’s famous hot springs. By building underground it opens up new spaces to provide such important facilities as toilets, a café and meeting rooms. There’ll also be a purpose-built Song School and a Discovery Centre to tell the Abbey’s story. As for the completion date, that’s likely to be 2021 at the earliest.

BEVERLEY MINSTER

From its sheer size and impressive architecture – it’s said that its beautiful west front was the model for that of Westminster Abbey – you could be forgiven for thinking that Beverley Minster is a cathedral. It is larger than many English cathedrals (and more impressive than some) but in fact it is a parish church, one of three in this busy market town in the East Riding of Yorkshire. Its title of Minster goes back to its foundation as an important Anglo-Saxon missionary teaching church, from where the canons went out to preach among neighbouring parishes.

It is hard to imagine that such a magnificent building was destined for destruction in 1548 during King Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries. Thankfully a group of the town’s wealthy businessmen bought the Collegiate Church of St John the Evangelist for its continued parochial use. Best known today as Beverley Minster, it is the Parish Church of St John and St Martin.

Beverley is often compared with its bigger sister, York Minster (page 258). They were built around the same time, from creamy white limestone quarried near Tadcaster and probably by the same masons. Less imposing it may be, but Beverley has an elegance and beauty all of its own.

Its twin west towers soaring skywards, the exterior of the building with its flying buttresses and arcading, statues set in canopied niches and the elaborate tracery of its windows, all hint at the glories to be discovered within.

The Minster owes its existence to St John of Beverley, who died in 721 and was canonised in 1037. Today his remains lie in a vault beneath the nave. A renowned preacher and evangelist, John was Bishop of York when he founded a monastery to retire to in what was then a remote, uninhabited spot. The town of Beverley grew up around it and thrived.

Miracles were attributed to him, ensuring a constant flow of pilgrims to his tomb and shrine. King Athelstan, grandson of Alfred the Great, credited John of Beverley with his victory at the decisive Battle of Brunanburh in 937. In thanksgiving he granted the Saxon church important rights and privileges and established a college of canons. When King Henry V triumphed at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, he attributed his success to St John and made him one of the patron saints of the royal family.

This is the third church on the site (little remains of its Saxon and Norman predecessors). Construction began in 1190 and continued for the next two centuries, its architecture encompassing the three main Gothic styles: Early English, Decorated and Perpendicular.

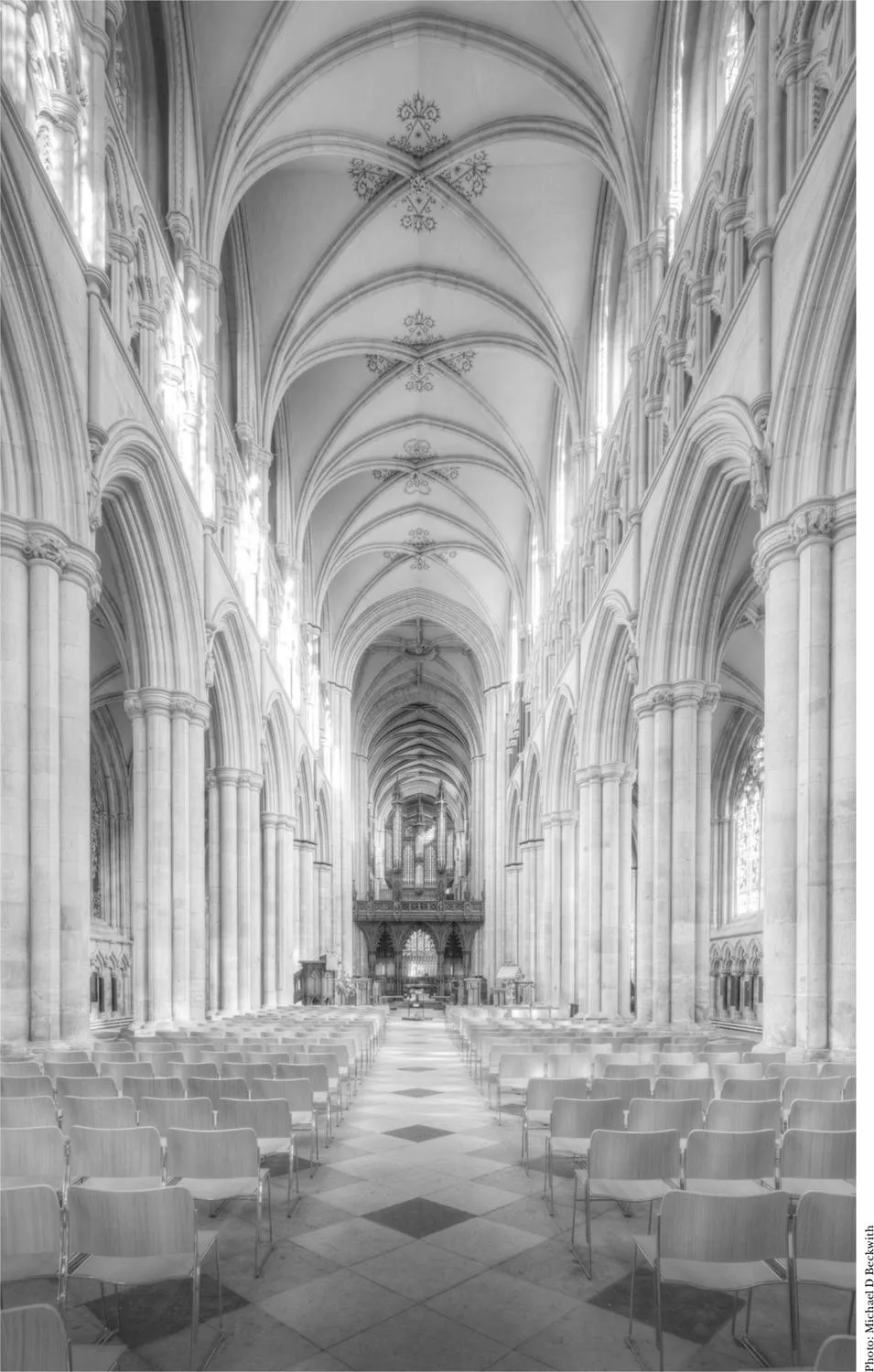

You enter through the door of the Highgate Porch, its carved triangular portico watched over by the seated Christ flanked by the twelve Apostles. Light floods the long nave, a vista of white limestone and polished Purbeck Marble, elegant arches, complex arcading and, stretching the full length of the Minster, a pale stone vault with painted tracery highlighting the gilded stone bosses.

Look back to the great west window, depicting the story of Christianity in the north of England, and below it, the magnificent west doorway. Tiers of stone statues under delicate canopies flank the flowing lines of a finely carved ogee arch, crowned by the figure of St John of Beverley. The carvings on the oak doors are of the Four Evangelists and their symbols, created, like the extraordinary canopy that tops the Norman font, in 1728 by the Thornton family of York.

Ahead, the high altar can be seen framed by the central arch of the oak screen that separates the nave from the chancel. Richly carved with saints, bishops and musical connotations, it supports the fine organ, its casing equally ornate, its pipes splendidly coloured.

In the medieval period, Beverley was the centre of secular music in the north of England. The Minster’s collection of over 70 medieval musician carvings in stone and wood, believed to be the largest in the world, has been the source of much of our knowledge of early musical instruments.

Many are at the base of the arches in the north aisle and atop pillars in the nave, but they are dotted all around the building as if tempting the visitor to seek them out. They show about twenty different instruments, including bagpipes, fiddles, trumpets, flutes, pipes, shawms and cymbals.

The quire and its early 16th-century carved wood quire stalls are one of Beverley Minster’s great glories. In the back row, tall canopies soar into a forest of pinnacles and crocketed spires while kings, saints and bishops stand proud above a lacy woodland of foliage and faces.

The ends of the stalls are carved with strange creatures and poppyheads, and beneath the seats is the largest set of misericords in any church in the country, 68 in all. Under each ledge that supported weary monks during long services, whole scenes of medieval life are portrayed in fine detail and often with a sense of humour or irony.

Originally built in around 1340 the quire has had a tortuous history. Mutilated and defaced, plastered over, hidden, then restored and rebuilt in 1826, like a picture gallery its niches are filled with mosaics of the twelve Apostles and saints, flanked at the base by stone figures associated with the life of St John of Beverley. A winding staircase leads to a platform at the top of the reredos where the saint’s shrine, richly embellished in gold and silver, was placed, centre stage for all to see.

The unusual trompe l’oeil floor of the quire, laid in the 18th century, gives the illusion of raised stepping-stones. It leads the eye to the high altar and behind it, the magnificent stone-carved reredos.

Alongside the altar is a plain, polished stone sanctuary chair, or frith stool, that dates from the earliest days of the Saxon monastery and is one of only two still in existence. The right of sanctuary for fugitives, given to the town of Beverley by King Athelstan, was abolished under King Henry VIII.

Adjacent to the high altar in the north quire aisle, the exquisitely carved 14th-century canopy of the Percy tomb is considered the jewel in Beverley’s not inconsiderable crown. The Percys were one of the richest and most powerful families in the north and the tomb is believed to be that of Lady Eleanor Percy who died in 1328.

A masterpiece of the stone carvers’ art – five master masons are said to have worked on it – it rises majestically in a flurry of figures, fruit and foliage. At the pinnacle on the north side, angels bearing the instruments of the Passion attend the risen Christ; on the south side, Christ receives the soul of the dead person into heaven. The whole canopy, a medieval view of paradise, somehow survived the Reformation and the Civil War and remains remarkably intact.

Also in the north aisle, the well-worn steps of a double staircase once led up to the chapter house, used by the college of canons. It was demolished when no longer required after the dissolution of the monastery, the stone sold to fund the purchase and preservation of the Minster.

The east window contains most of the me...