- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

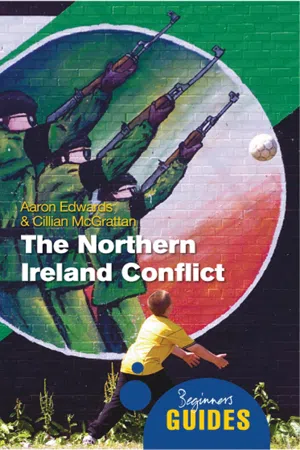

About this book

The definitive study of this troubled region

The Northern Ireland conflict is the most protracted and bitter campaign of terrorist violence in modern history. Despite decommissioning and political compromise, violent incidents are still rife and Unionists and Nationalists are as segregated as ever. This landmark introduction uses the latest archival material to chart the history of The Troubles and examine their legacy. Exploring the effects of sectarian violence, British intervention, and efforts to improve community relations, this astute book extends beyond the usual cliches found elsewhere.

The Northern Ireland conflict is the most protracted and bitter campaign of terrorist violence in modern history. Despite decommissioning and political compromise, violent incidents are still rife and Unionists and Nationalists are as segregated as ever. This landmark introduction uses the latest archival material to chart the history of The Troubles and examine their legacy. Exploring the effects of sectarian violence, British intervention, and efforts to improve community relations, this astute book extends beyond the usual cliches found elsewhere.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The origins of the conflict, 1921–72

Partition and the birth of the state

The Northern Ireland state was formed between 1920 and 1922, at a time when the British government was recovering from a massive drain on its financial coffers caused by having fought a catastrophic total war. The effects of World War I were far reaching across Europe. In Germany, Communist and Fascist groups arose, backed by the muscle of demobilised soldiers and disgruntled unemployed workers, and jostled with one another in the streets against the backdrop of diminished authority exhibited by the Weimar Republic’s social democratic government. Meanwhile, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was born out of the Bolsheviks’ bloody seizure of power in 1917, while the Ottoman Empire perished amidst the chaotic turmoil of an Arab revolt and the rise of ethnic nationalism. A similar fate overtook the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, which dissolved in 1918 following military defeat in World War I. From Constantinople to Berlin old certainties were overturned, regimes rocked and toppled, and battle scars were left across the world. Ireland did not remain insulated for long from the revolutionary and counter-revolutionary forces setting the Continent ablaze. Despite the collapse of three imperial dynasties, the British Empire continued to extend its frontiers, most notably when the League of Nations allocated Britain responsibility for the mandated territories of Iraq, Palestine, and Transjordan,1 although the government was seeking ways to contract its obligations closer to home.

Fearful of similar turmoil taking root, Unionist politicians elected to the newly established Northern Ireland Parliament in 1921 attempted to erect bulwarks against what they saw as the ‘twin evils’ of communism and republicanism, marshalling all available resources at their disposal to quell dissent among the working classes.2 The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) saw this as the perfect opportunity to strengthen its control over the local administration. Representing the majority Ulster Protestant tradition in the north-east counties of Ireland, the Unionists had won the first elections to the local parliament by a comfortable majority. In British eyes partition was an effective way of managing a conflict many in London viewed as a curiosity; in this instance it would copper-fasten the Union while staving off any further complications in Ireland.

BACKGROUND TO THE CONFLICT

Nationalists and unionists are divided over the basic causes and proposed solutions to the Northern Ireland conflict. Nationalists, for example, often date the conflict to the Anglo-Norman invasion of 1169 and point to subsequent key events to illustrate Britain’s oppressive role in Irish history and the frequent resistance by the Irish. Events such as the massacres and repression by Cromwell during the 1640s, the suppression of the United Irishmen Rebellion during the 1790s, the Famine years of the 1840s, and the execution of the leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising serve as critical reference points in that nationalist narrative. The unionist historical narrative is also marked by key events such as the massacres of Protestants at the hands of Catholics in 1641, the victory of King William of Orange over the Catholic King James II in 1690, the resistance to British attempts to impose ‘Home Rule’ in 1912–14 and the sacrifices of the Ulster Division during the Battle of the Somme in 1916. For unionists, these events illustrate a history of Catholic oppression and betrayal and Protestant loyalty to the Crown and the Union. The ‘siege mentality’ fostered by that history is often expressed in the slogan ‘No surrender’.

British attempts to cut off or ‘insulate’ Westminster politics from the ‘Irish question’ reached a high point in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries with the idea of ‘Home Rule’, in which a Dublin parliament would rule Ireland but would still be ultimately answerable to London. During the 1910s these attempts coincided with – and, to a large extent, inspired – a growing militarisation and radicalisation of Irish society. The growing gulf between the two sides was illustrated in the War of Independence fought by the Irish Republican Army against the British (1919–21) and the mobilisation of Protestant support to defend the Union in the North. The British ‘solution’ to the problem was to impose a settlement that neither side really wanted – partition the thirty-two counties of Ireland into the twenty-six in the south that had a Catholic-nationalist majority and the six in the north that had a Protestant-unionist majority, each to be governed by devolved parliaments in Dublin and Belfast respectively.

The Northern Ireland state was a unique construct in that it reinforced the power of Ulster Protestants, who held a majority share of the population in the six counties in the north-east of Ireland, but who were a minority community in the island of Ireland, with their demographic roots in the Plantation migrants who had crossed to Ireland in the seventeenth century. The Ulster Protestants became dominant in this area. What made the north-east counties so different from the rest of Ireland was their close proximity to Great Britain, a heavy industrial base concentrated in the Lagan Valley in Belfast, and unfettered access to the financial markets of the British Empire. As the Unionist leader Edward Carson proclaimed in 1916: ‘it was an “utter fallacy” for the economically incompetent south and west of Ireland to wish to rule the North’.3 Arguably, there was an economic logic to partition and, when combined with the uneven development of capitalism in Ireland, it was bound to have an effect on the type of society built up in the region.

Northern nationalists, who comprised about a third of the population of the newly formed state, desired an end to partition, and remained highly ambivalent about participating in the state’s social and political structures. In fact, the architecture of the political structures guaranteed nationalist disquiet: the initial proportional electoral system was replaced in 1925 by a majoritarian, first-past-the-post arrangement meaning that nationalists could hope for no more than ten to twelve of the fifty-two Stormont Parliament seats at any election. This situation was exacerbated by the re-drawing of electoral boundaries – particularly at the local government level – to ensure Unionist majorities. Gerrymandering, as this practice is known, had a profound effect on Nationalist politics in Northern Ireland. In 1920, for example, there existed twenty-five Nationalist-controlled councils; however, by 1925 – due to the abolition of proportional representation and the rigging of electoral wards – these had been reduced to four. Crucially, Derry City, despite its large Nationalist majority, comprising around sixty-five per cent of the population, was run by a Unionist-dominated corporation until 1968.4 From the 1930s onwards, nationalists instead looked to the Irish Free State in the south to improve their situation and formed what effectively became ‘a state within a state’.5

In many respects state-building was a protracted process in Northern Ireland and relied heavily on the professionalism of the local civil service, an organisation equally divided in its bureaucratic tendencies between populist and anti-populist interest groups centred round Unionism’s principal leaders.6 Populists tended to use patronage at their disposal to curry favour among their supporters, many of whom held positions of social rank in the Protestant community. Conversely, anti-populists resisted the temptation to place loyalty above a commitment to a more meritocratic ethos commonly found in Great Britain. Populists complained bitterly about the appointment of Catholics to government posts and preferred to fill gaps in the province’s bureaucratic system through a dual-edged process of cronyism and discrimination. Extraneous factors such as socio-economic upheaval played havoc with the local economy, which was already reeling from the stress placed upon it by war-time demands. Unemployment in the province rocketed in the 1920s and reached an incredible twenty per cent by the middle of the decade. This severely affected the local workforce, who exercised their right to protest by downing tools and balloting for strikes, a tactic which serve to cripple the economy still further. The Unionist government appealed to ethnic unity as a means of offsetting the labourist sympathies of a hungry working class. Yet nothing could stymie the challenges now evident within the Protestant community, from both Independent Unionists and, after 1924, the Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP).

Unionist resilience in the face of such challenges soon proved resurgent. The local regime was greatly aided in its strategy of divide and rule by the upsurge in sectarian tensions and political violence across Belfast. In 1920–2 between 452 and 463 people were killed and 1100 injured as the province became subject to the brinkmanship of rival paramilitary gangs.7 Several clandestine organisations emerged amidst the calamity of armed conflict precipitated by state formation and included the Irish Republican Army (IRA), supported by the newly established government in Dublin, and the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), which was soon to be absorbed into the local security force apparatus. Despite most Protestants being unionist in their political viewpoint not all were convinced that the state’s new political masters were competent in their handling of social and economic affairs. On the other hand, there were others who thought that the new regime was too weak-kneed in the face of socialist and republican opposition. The Unionist government was to remain, until its eventual collapse in March 1972, a hostage to these conflicting tendencies.

CONSERVATIVE UNIONISM: THE ULSTER UNIONIST PARTY

The UUP was formed in 1905 to resist attempts by Westminster governments to impose Home Rule on Ireland and to protect Protestant interests. Although the establishment of Northern Ireland represented something of a set-back to the first objective, the party quickly adapted to the new arrangement – aided by the fact that it comprised the majority in the devolved parliament.

Although nationalists often question the ambiguous relationship between the UUP and the more extreme elements within the broad unionist family, UUP politicians and supporters point to the fact that it frequently served to restrain loyalist violence. Likewise, while nationalists point to instances of misrule and discrimination by the UUP-led Northern Irish governments, supporters of the party claimed that the real agenda of Northern nationalists remained reunification rather than civil rights. Indeed, the actions of UUP leaders such as Terence O’Neill during the 1960s, Brian Faulkner during the 1970s, and David Trimble during the 1990s and 2000s strongly suggest a conservative or ‘gradualist’ approach to change and reform – as distinct from the wholesale, far-reaching proposals advocated at different times by nationalists and republicans.

The split in the Unionist government between populists and anti-populists persisted throughout the 1930s, Unionist prime ministers frequently acting on the basis of what they thought was best for their Protestant working-class supporters. For example, both Sir James Craig and his successor John Miller Andrews were populist in their outlook, while Sir Basil Brooke and his successor Terence O’Neill added a distinctly anti-populist flavour to their style of government in later years. Such division reinforced the disagreement over the exact political strategy to be adhered to by Unionists during these years, an internal dispute that would persist through later generations.

Despite these religious and political divisions, the ‘outdoor relief riots’ of 1932 brought together Protestants and Catholics to protest against the inequitable treatment handed out to them by the Belfast Poor Law Guardians – the body that was appointed to administer relief to unemployed workers and their families. By 1934, the working classes marched the streets of Belfast in radical unison, with a mainly Protestant Shankill Road contingent making the annual pilgrimage to Bodenstown cemetery in County Kildare for rousing anti-British speeches at the graveside of the eighteenth-century republican martyr Wolfe Tone. However, within a matter of months the potential for cross-sectarian harmony was undermined when a murder campaign by loyalist paramilitaries threatened to shatter the brittle rigidity of solidarity fostered among Protestant and Catholic workers. Predictably, sectarian rioting followed the annual Orange Order parades in Belfast in July 1935. Catholics soon came to view themselves as a besieged minority in a hostile society.8

The death of James Craig (Lord Craigavon), Northern Ireland’s first prime minister, in November 1940, sent shock-waves throughout the Unionist community. He was succeeded by John Miller Andrews – brother of renowned Titanic architect Thomas Andrews – who preferred to take a more conciliatory attitude towards industrial militancy after 1941. At a time when British politicians increasingly questioned the province’s contribution to the war effort, Andrews’ policies left many of his colleagues uneasy and soon proved politically fatal. Northern Ireland alone accounted for ten per cent of the total number of days lost to strikes in the UK, while accounting for only two per cent of industrial output.9 Andrews resigned as prime minister in 1943, allowing his Minister of Commerce Sir Basil Brooke, the nephew of the Chief of the Imperial General Staff Sir Alan Brooke, to take his place. As a former British Army officer himself, Brooke took a more military approach to prime ministerial matters in Belfast. In his later years there was much criticism that he spent more time on his private estate in Fermanagh than behind his desk or in the parliamentary debating chamber. Northern Ireland politics remained something of an amateurish affair as the Belfast Parliament met infrequently, with many politicians attending on an ad hoc basis.

MILITANT LOYALISM: THE UVF

Militant loyalism is often characterised as the least respectable component of the Ulster Unionist political project, yet it has been around since before the third Home Rule crisis of 1910–14. Retired British Army officers were complicit in the raising of the original UVF as a paramilitary army to oppose the possibility of Home Rule government for Ireland. The UVF was staffed by many serving British Army NCOs and officers and was later subsumed into the 36th (Ulster) Division, which fought on the Western Front in World War I. In 1920 the UVF’s commanding officer, Lieutenant-General Sir George Richardson, issued an order disbanding the UVF and calling upon its men to disperse into the ranks of the newly constituted Ulster Special Constabulary. The old UVF was consigned to the history books.

T...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Chronology

- Note on terminology

- Introduction

- 1 The origins of the conflict, 1921–72

- 2 Direct rule and power sharing, 1972–4

- 3 ‘Refereeing the fight’: the limitations of British intervention, 1974–85

- 4 The peace process, 1985–98

- 5 Institutional stalemate and community relations, 1998–2008

- 6 ‘An age-old problem’? Why did the Troubles happen?

- Conclusion: troubled legacies

- Further reading

- Endnotes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Northern Ireland Conflict by Aaron Edwards,Cillian McGrattan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.