![]()

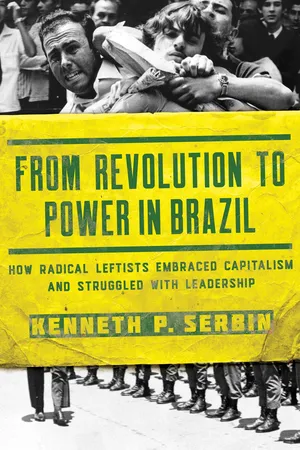

PART I

REVOLUTION AND REPRESSION

![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Surprise of the Century

Manoel had to make a split-second decision.

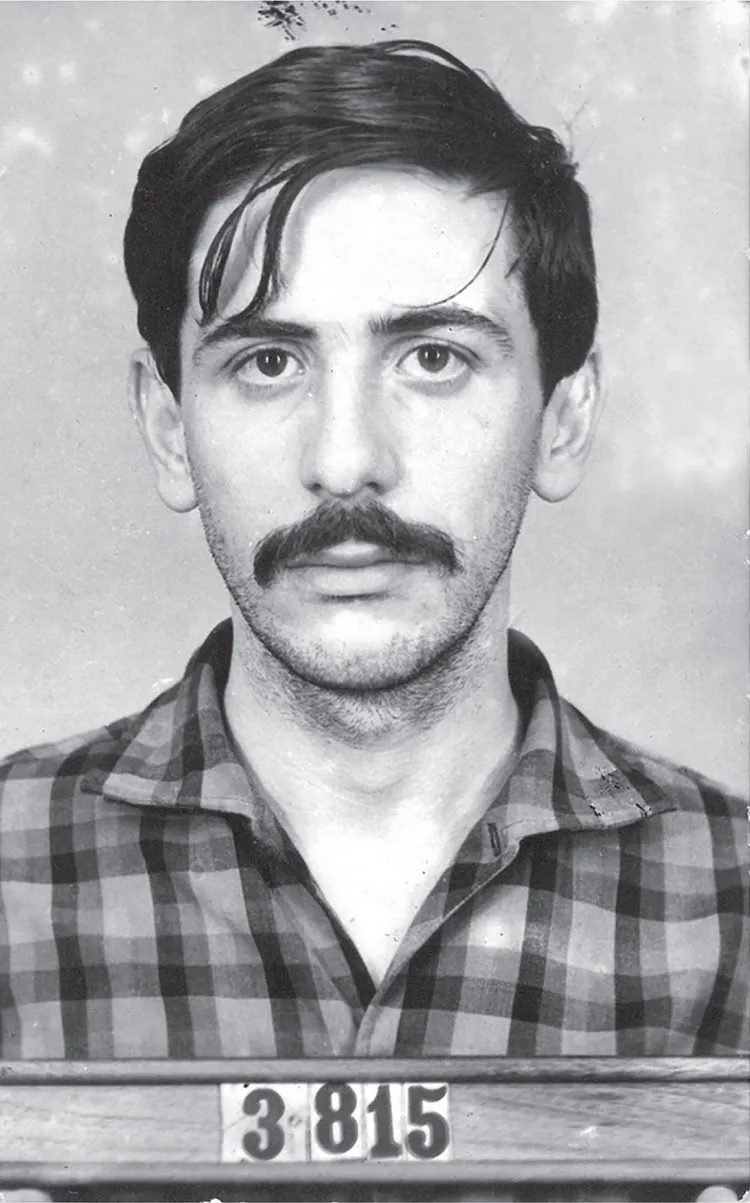

Minutes earlier, on the afternoon of September 4, 1969, he and three fellow revolutionaries had commandeered the Cadillac limousine carrying U.S. ambassador Charles Burke Elbrick from his residence to the embassy in downtown Rio de Janeiro after their comrades in other vehicles had surrounded and halted the limousine. Manoel had abandoned plans for college and a budding career as a publicity agent to fight against Brazil’s military dictatorship. Within the ALN, he quickly became one of Brazil’s most active guerrillas. The tall and wiry Manoel participated in robbing a dozen banks and other businesses, stealing explosives, and blowing up police and military targets.1 In one bank robbery, a policeman died from a guerrilla’s gunshot, but it was unclear who hit the officer.2 In a firefight with two policemen, one of Manoel’s accomplices took five bullets in the abdomen, while another killed one of the officers.3 Just twenty-three, Manoel was flush with the adrenaline, ambition, idealism, and hubris of a new generation of Latin American youths. They had come of age between the 1959 Cuban Revolution and 1968, the year that marked a high point of a global revolution in politics, customs, religion, and gender relations. They needed such bravado to challenge the highly repressive government that had seized power in 1964 with U.S. support.

Virgílio Gomes da Silva, the tough leader of the abduction team whose nom de guerre was Jonas, and Manoel, the second-in-command, flanked Ambassador Elbrick in the back of the limo with their revolvers ready. In the front seat, two other armed comrades forced the chauffeur to sit between them. One car in front of the limousine and another behind carried other plainclothes guerrillas, who gave cover as the guerrilla driver, wearing the chauffeur’s cap, negotiated the ambassador’s vehicle through the streets of one of Rio’s busiest residential neighborhoods. Minutes later they ascended a secluded street that wound up a heavily forested hillside. Soon they reached a vacant lot, where a getaway van was waiting.

Manoel and Jonas removed Elbrick from the limo and ordered him to close his eyes. But Elbrick kept them open.

In August 1968, the U.S. ambassador to Guatemala, John Gordon Mein, had been shot to death as he attempted to flee guerrillas attempting to kidnap him—the first U.S. ambassador killed in the line of duty. In October 1968, the ALN carried out its first justiçamento, an execution in the name of revolutionary justice, killing an American. Marco Antônio Braz de Carvalho, the first commander of the ALN’s armed operations, and members of another revolutionary organization shot U.S. Army captain and Vietnam veteran Charles Rodney Chandler, believing he had come to Brazil to spy for the CIA and teach methods of torture. In June 1969, less than three months before accosting Elbrick, Manoel and other ALN members bombed the building in São Paulo housing the U.S. Chamber of Commerce shortly before New York governor Nelson Rockefeller was scheduled to appear.

Fearing that he was about to be executed, Elbrick tried to deflect Jonas’s gun. Manoel believed the ambassador wanted to grab the weapon. He viscerally knew how easily an operation could spin out of control. If Jonas, Elbrick, or anybody else were shot, this high-stakes gamble could end disastrously.

Grasping his own revolver, Manoel struck the ambassador’s forehead with the cylinder just hard enough to stun him. Only then did Elbrick, now bleeding, begin to understand that his abductors did not want to kill him—at least not yet.4

“‘I’ve got to stop this guy,’” Manoel remembered thinking at the time. “‘I’ve got to show him that he’ll come to an inglorious end, that his desperate attempt at self-defense will get him nowhere. I’ve got to bring him to his senses and back to reality.’ That’s why I thought of hitting him with my gun. He was shocked, and it hurt. He got scared, and that allowed us to achieve our objective. . . . He apologized, not me. I shouted, ‘No, I’m the one who should apologize. I was the violent one. You didn’t do anything to blow the violence out of proportion. I’m the one who acted violently, but it was for your safety and ours too.’”5

Manoel exemplified the guerrillas’ complicated attitude toward violence. They had no qualms about killing military targets such as Chandler, but they wanted to avoid harming innocent civilians. “Hurting the ambassador was horrible for all of us, especially for the comrade who hit him,” accomplice Fernando Gabeira, an October 8 Revolutionary Movement (MR-8) militant and journalist, would write of Elbrick’s injury in his memoir. “Every chance he got, he [Manoel] wanted to know how he was doing, whether he was feeling pain, whether he was still bleeding.”6 However, Elbrick was a politically valuable prisoner who represented the U.S. government. After releasing the chauffeur, the guerrillas left a threatening manifesto in the limousine. Twenty-one-year-old revolutionary Franklin Martins wrote the 850-word document in the moralistic, uncompromising, direct style typical of Brazil’s armed militants. It demanded a costly political ransom and left no doubts as to Elbrick’s fate if it were not met:

Today revolutionary organizations detained Mr. Charles Burke Elbrick, the United States ambassador, and, taking him to a location within Brazil, are keeping him in custody. This is not an isolated episode. It is one in a series of revolutionary acts already carried out: bank robberies, committed in order to collect money for the revolution and to recover what the bankers have taken from the people and from bank employees; attacks on barracks and police stations, in order to obtain arms and ammunition for the struggle to overthrow the dictatorship; attacks on prisons, in order to liberate revolutionaries and to return them to the people’s struggle; explosions of buildings that symbolize oppression; and the execution of killers and torturers. . . .

Mr. Elbrick represents within our country the interests of imperialism, which, allied with the leaders of big business, large landowners and wealthy Brazilian bankers, prop up a regime of oppression and exploitation. . . .

The life and death of the ambassador is in the hands of the dictatorship. If it complies with two demands, Mr. Elbrick will be freed. If it does not, we will be obliged to carry out revolutionary justice. Our two demands are:

(a) The release of fifteen political prisoners. The fifteen revolutionaries are among the thousands who suffer torture in military prisons throughout the country, who are beaten, mistreated and who endure the humiliations imposed by the military. We are not asking the impossible. We are not demanding that innumerable combatants killed in the prisons be brought back to life. They, of course, cannot be freed. Someday they will be avenged. We demand only the freedom of these fifteen men, leaders of the struggle against the dictatorship. From the standpoint of the people, each of them is worth one hundred ambassadors. But from the standpoint of the dictatorship and its exploitation, a U.S. ambassador is also worth a lot.

(b) The publication and reading of this message, in its entirety, by the principal newspapers, radio stations and television outlets throughout the country.

The fifteen prisoners must be transported on a non-commercial flight to a specific country—Algeria, Chile or Mexico—where they will be granted political asylum. No reprisals must be taken against them, or else there will be retaliation.

The dictatorship has forty-eight hours to respond publicly whether it accepts or rejects our proposal. If the response is positive, we will release the list of fifteen revolutionary leaders and wait twenty-four hours for their transport to a safe country. If the response is negative, or if no response is given by the deadline, Mr. Elbrick will be executed. . . .

Finally, we want to warn those who torture, beat, and kill our comrades: we will no longer allow this to continue. We are giving our last warning. Whoever continues to torture, beat, and kill had better be ready. Now it is an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.

National Liberating Action (ALN)

October 8 Revolutionary Movement (MR-8)

They had taken an enormous risk. Shocking even fellow revolutionaries, the kidnappers had transgressed an unspoken international norm. Political kidnappings had a history reaching back to at least the early nineteenth century. But this was the first time anywhere that someone had kidnapped a U.S. diplomat.7 In Washington, DC, President Nixon received news of the abduction from his assistant for national security affairs, Henry Kissinger, and was said to personally follow the situation.8 The kidnapping made international headlines. “Gunmen Kidnap U.S. Envoy in Brazil,” stated a three-column, front-page headline in the September 5, 1969, edition of the New York Times. In an editorial the next day, the paper warned of the “escalating urban terrorism of revolutionary left-wing groups in Latin America,” but also criticized Brazil’s military rulers for “oppressive policies” that allowed terrorism to flourish. The paper also published an English translation of the revolutionary manifesto.9 “It was just unheard of to touch a diplomat,” Valerie Elbrick, the ambassador’s adult daughter, who was in Yugoslavia when she received the news of the abduction, recalled four decades later. “That kidnapping was the surprise of the century to the Brazilian government.”10 It also caught the State Department’s Office of Security completely off guard, prompting extensive new efforts to safeguard U.S. overseas posts, including an increase in the use of “follow cars” to protect ambassadors in transit and the adoption of armored vehicles in high-risk capitals.11

Elbrick held great importance not only because of his country’s superpower status. He had a long, distinguished career, rising to the rarely awarded rank of career ambassador, the highest in the U.S. Foreign Service. Though he was under discussion for the ambassadorship in Moscow, Elbrick preferred Brazil because of its importance for the United States and his lifelong curiosity about the country, Valerie recalled.12 In September 1969, he had been in Rio less than two months, but with his fluent Portuguese (from service in Portugal) he communicated easily with the kidnappers. If Elbrick were harmed, political leaders and diplomats everywhere would be further shocked, and U.S.–Brazilian relations would be jeopardized.

IN 1969, THE generals’ drive to make Brazil a geopolitical player seemed within reach. As the “Brazilian miracle” boosted growth, the country’s GDP approached the top ten in the West. It was now the world’s ninth-largest automaker. However, the suffocation of democracy, the growing use of torture and intimidation, and the desire for revolution prompted the guerrilla groups to step up their actions.

One of the most important guerrilla leaders was fifty-five-year-old Carlos Marighella, the founder of the ALN. A former congressman and high-level PCB leader, Marighella dissented strongly from the party’s official refusal to take up arms. As it became clear that the military would not return the government to civilians, Marighella focused on not just restoring democratic liberties, but also on overthrowing the institutions that hampered the achievement of social justice. He went to Cuba in 1967 to obtain support for guerrilla activity in Brazil. During an interview on Cuban radio, Marighella declared that Brazilian revolutionaries needed to “seize power violently and destroy the bureaucratic-military apparatus of the state, replacing it with a people’s army.”13 He soon quit the PCB, as would half of its 55,000 members that year, ending the party’s half-century hegemony on the Brazilian Left. Also, that month Che Guevara exhorted revolutionaries in Latin America to create “many Vietnams” to end U.S. domination and help destroy the international capitalist system. Inspired by the variety of revolutionary theories circulating in Latin America, the ex-PCB members and other prorevolution Brazilians formed more than three dozen organizations to resist the government.

Marighella started the ALN in 1967. As its name indicated, the ALN fought mainly for “national liberation” from imperialism and U.S. dominance. The much smaller MR-8, operating mainly in Rio, aimed to immediately establish a socialist regime. Other organizations adopted their own strategies. They all sought to overthrow the dictatorship, but they often diverged over obscure ideological points and engaged in geographical and political factionalism. Within the ALN itself, the college-age guerrillas from São Paulo developed an air of superiority toward their high-school-age ALN counterparts in Rio. Marighella hailed from Bahia, the state with the country’s deepest African heritage. He was a mulatto—his father an Italian immigrant, his mother a descendant of slaves. A poet and passionate devotee of Brazilian culture, Marighella tried to stand above the many divisions within the resistance. A survivor of torture, imprisonment, and bullet wounds suffered in a clash with the police after the coup, he became the armed Left’s most famous and most charismatic leader.14

Che was captured on October 8, 1967—a date that inspired MR-8’s name—while trying to start a revolution in Bolivia. Bolivian soldiers executed him the following day. Despite Che’s demise, his ideas continued to exercise powerful influence over young people throughout Latin America. He became practically a saint of the Latin American radical Left. Radicals such as the Weathermen in the United States and guerrillas in Latin America and other Third World countries adopted violence to foment political and social change. However, Guevara’s ominous rhetoric belied a huge miscalculation in terms of inspiring guerrilla action: Latin America was not another potential Vietnam because, other than the failed Bay of Pigs paramilitary operation in Cuba in 1961 and a small-scale intervention in the Dominican Republic by U.S. (and Brazilian) troops in 1965, no U.S. forces had invaded the region in the 1960s.15 It would be tougher to inspire anti-imperialist guerrilla action.

For the ALN, the dictatorship embodied U.S. interests in Brazil. The ALN was the largest guerrilla organization, with about three hundred fighters and a total of six th...