- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Commercial Fishing on the Outer Banks

About this book

Fishing on the Outer Banks for subsistence began over 1,000 years ago with the Algonquin Indians, who made their summer camps on the islands. They came for the seafood and learned how to fish for various species during each season. Some of their fishing methods are still used by local watermen. The early settlers to the area were also fishers for sustenance. It was not until the Civil War, however, when they became commercial fishermen. Historic shad runs combined with the building of infrastructure such as an ice plant, roads, and bridges finally made possible the exportation of their catches to northern markets. In the 1950s, tourists started trickling in, and restaurants began dotting the landscape, promoting the consumption of fresh seafood. Today, in an economy ruled by tourism, fishing for profit still plays a strong role. What began in the 1660s with a shipment of 80 barrels of whale oil has continued to the present with internationally coveted catches of bluefin tuna. Although the fishing industry is threatened today as never before, commercial fishermen will continue to develop new markets and fight for their livelihoods.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

One

FROM PROLIFIC

TO PROTECTED

TO PROTECTED

Outer Bankers have always made a living from the sea, by sheer intentional will or by taking advantage of uninvited but welcomed opportunities. As recorded in the 1660s, the first settlers living on Colington Island sold 80 barrels of oil rendered from dead whales, called drift whales, like this whale that washed up near Southern Shores beach in 1955. (Courtesy of NPS, CHNS.)

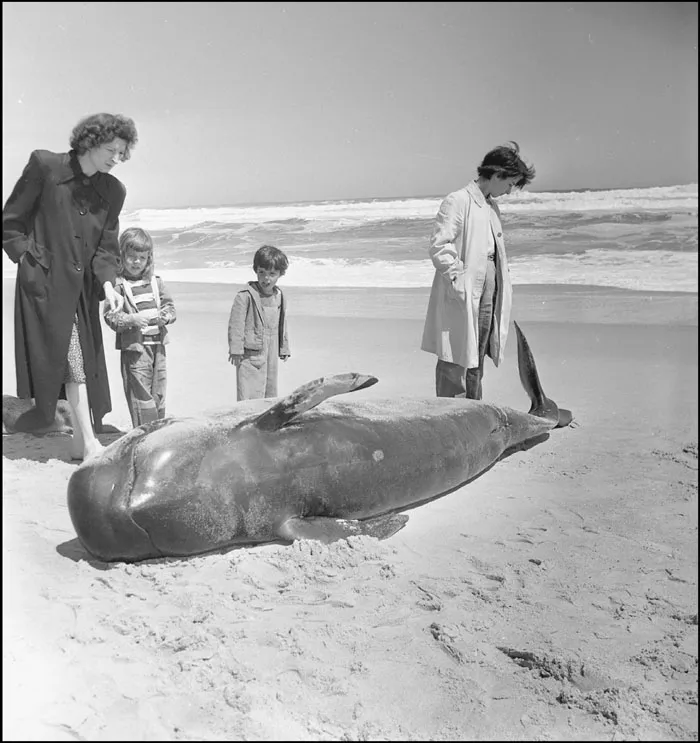

Families would come together to process drift whales. Neighbors would set up portable, makeshift operations to cut up and cook down the blubber in iron pots over wood fires. It could take up to 10 smelly days to render all of the fat into precious whale oil. The whale in this 1971 photograph, taken on the Cape Hatteras National Seashore, was put to no such use. (Courtesy of NPS, CHNS.)

Twice yearly, whales migrate along a specific route just off of the Outer Banks. This whale’s life ended on Portsmouth Island in the 1940s. Although New England whalers used Cape Lookout, North Carolina, as a base of operations, there is no written or oral record that deliberate whaling took place on the northern Outer Banks. (Courtesy of Aycock Brown Collection, OBHC.)

It is possible that enterprising local fishermen learned and used whaling methods developed elsewhere. Tall dunes or a tower were needed for the lookout to spot the passing mammals. A boat would be launched into the pod so that a harpooner could hook onto and exhaust a whale. This pilot whale washed up near the old Coast Guard station in Kitty Hawk in 1954. (Courtesy of Aycock Brown Collection, OBHC.)

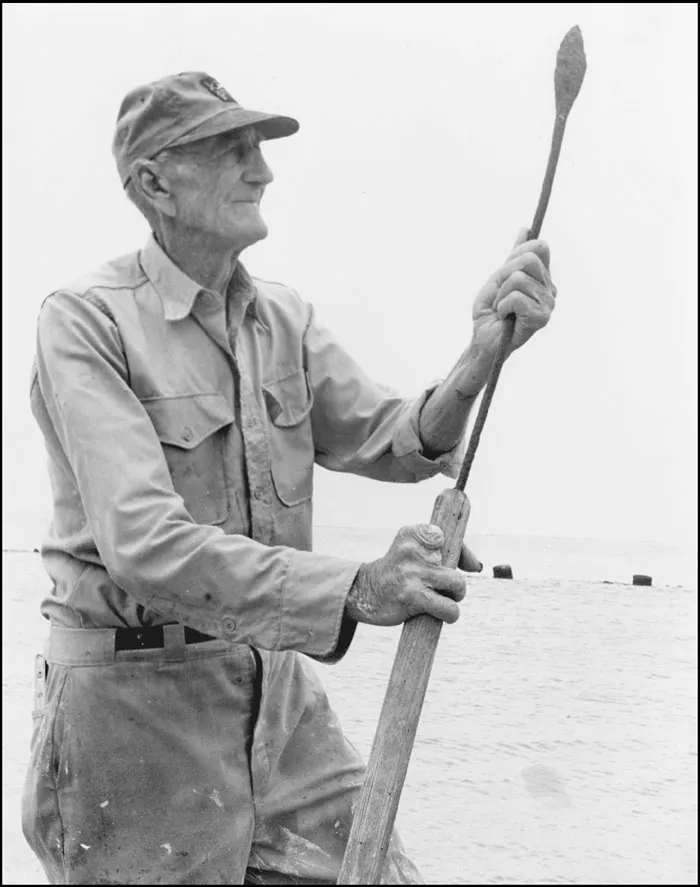

This man from the Cape Lookout area posed with a whaling spear. Whalers were at a great disadvantage in the ultimate battle between man and beast. Six men in an open wooden boat with only handheld harpoons and coils of rope were pitted against a huge, intelligent creature. By the look of this man’s right hand, he also had an unforgiving encounter of some kind. (Courtesy of Bruce Roberts Collection, OBHC.)

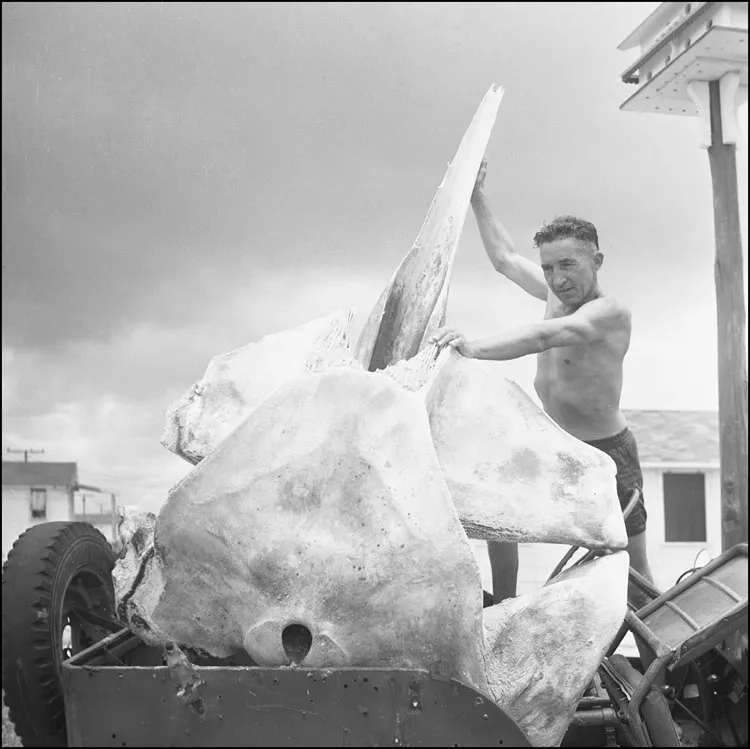

Before the use of petroleum, whale products were essential. Lighthouses used oil to keep lanterns burning. Spermaceti, the highest-quality oil extracted from sperm whale heads, lubricated fine instruments. Baleen, the bonelike feeding filters, was used for corsets and umbrella ribs. This whale skull was loaded in a jeep at Caffey’s Inlet in Kitty Hawk around 1953. (Courtesy of Aycock Brown Collection, OBHC.)

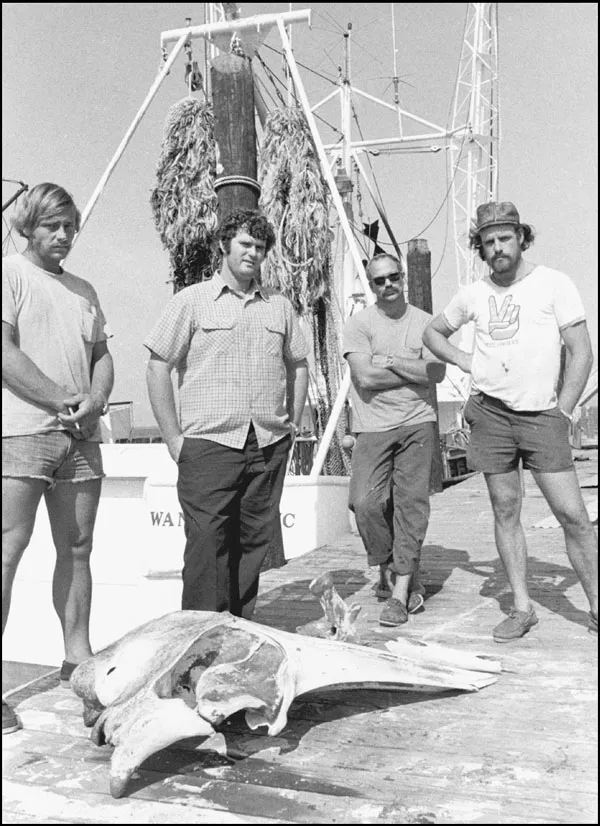

In the 1980s, from left to right, Doug Bateman, Capt. Billy Carl Tillett, John Arendts, and Vernon Lewark pose with a whale skull and vertebrae that were brought up in a net on the Linda Gayle. Locals used to love to show off whalebones. Whalebone Junction in Nags Head was named for a 72-foot-long whale skull and backbone displayed in front of the Midgett family’s gas station. (Courtesy of Billy Carl Tillett, photograph by J. Foster Scott.)

A disoriented pilot whale, perhaps chased by sharks, washed up on Duck’s sound side in October 1954. The Navy men stationed at that quiet outpost tried, but failed, to save the whale’s life. Nowadays, Duck is a premier vacation destination, but in the 1950s, besides the Navy men, only a few fishing families inhabited the desolate area. (Courtesy of Aycock Brown Collection, OBHC.)

This kayaker must have hoped someone else besides him saw the massive whale breaching near Jennette’s Pier in Nags Head. It was most likely a humpback since they tend to swim close to shore. They pass by in December and January on their way to the Caribbean to breed and give birth and, then again, in March and April on their way to polar waters for summer feeding. (Courtesy of Daryl Law.)

Porpoise, or bottlenosed dolphin, fisheries existed in 1790 on Portsmouth Island near Ocracoke and, later, on Hatteras Island. According to a diary kept by one of the last operators, Hatteras native William Harris Rolinson, the fishermen absolutely detested the work. It was near-freezing cold, but more unsettling, it was a heartless business. Each crew was made up of 14 to 18 men. A “spy” would spot a school and raise a flag to alert men waiting in dories 150 yards offshore. They would quickly row to the beach releasing one end of a 400-yard barrier of 18-inch mesh, heavy-twine net, cutting off the porpoises’ forward path. A remaining boat would come to shore after the mammals had passed, thus trapping them in a large semicircle. In this 1928 photograph, Hatterasmen use a sweep-seine net within the outer net to herd the porpoises to shore. (Courtesy of Marine Mammal Program, Division of Mammals, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.)

Taking advantage of migration patterns, porpoise fishing started in late December and ended in early April, usually an unproductive time for watermen. The men were grateful for the paycheck, meager though it was. Fishing and processing plant positions were given to local men, but supervisory roles were held by out-of-state entrepreneurs. Three separate processing plants were located sound side on lower Hatteras Island. Although extremely clever, once in the nets, the porpoises seemed resigned to their fate. Lou Angell wrote that the scraping of an oar along the warp lines would keep them from swimming under the net, even though they could have easily done so. If one did happen to jump the cork line, it was difficult to keep the others from following. The fishery lasted on and off from 1790 to 1928, with the heyday being in the late 1800s. (Courtesy of Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.)

Jarvis Midgett, the tallest young man with a cap, and Augustus Austin, the smaller fellow, watch as a dolphin is skinned on February 10, 1928, the day Dr. Remington Kellogg of the Smithsonian visited Frisco, North Carolina. The melon, a small organ involved in echolocation above the porpoise’s jaw, had already been taken for the high-quality oil it yielded. Called Nye oil after the man who perfected it, the lubricant was used in clocks, watches, and other superior mechanisms. Blubber was rendered down for oil, the one-inch-thick hide was used for machine belts, and the carcasses were used for fertilizer. The men hated hooking the porpoises in their blowholes, dragging them ashore, and stabbing them. Even the horses that transported them in carts were afraid of the scene, and the strongest man had to handle the teams. (Courtesy of Marine Mammal Program, Division of Mammals, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.)

On April 19, 1954, people gathered to see what all the excitement was about when boats came into Wanchese harbor with drum spilling over the sides. It was the result of a springtime run of channel bass at Oregon Inlet. The crews of Willie Etheridge Sr., Dewey Tillett, ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. From Prolific to Protected

- 2. Heritage Fisheries

- 3. Prized Catches

- 4. Beyond Subsistence

- 5. Stewards of the Sea

- 6. Local Mainstays

- 7. Gearing up for Change

- 8. Big Fish, Big News

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Commercial Fishing on the Outer Banks by R. Wayne Gray,Nancy Beach Gray in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.