eBook - ePub

Counterculture UK – a celebration

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

What is counterculture?

– It's an alternative lifestyle…

– The ideas that spread a revolution…

– A movement that changes the world…

This new collection of essays celebrates the incredible originality of British post-war culture. British Art, film, theatre, dance, literature and music have attracted international recognition, from the Angry Young Men to the Sex Pistols to Grayson Perry. Now gaming, the internet and social media enable creative communities to flourish and either fight for social justice – or just be entertained,.

Can we find the creative inspiration to succeed in a post-capitalist future>?

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Counterculture UK – a celebration by Mark Sheerin, Coco Khan, Susan Murray, Mark Edward, Penny Pepper, Paul Quinn, Hayley Foster Da Silva, Ellen Cheshire, Charlie Oughton, Simon Smith, Jack Bright, Ben Graham, Em Ayson, Tim Burrows, Tim Garrett, Bella Qvist, Rebecca Gillieron, Cheryl Robson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Kunst & Volkskultur in der Kunst. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Aurora Metro BooksISBN

9780993220715

Topic

KunstSubtopic

Volkskultur in der KunstART

How the Rebels Got Rich

Mark Sheerin

Sunflower Seeds by Ai Weiwei, at the Tate Modern

Art can be dangerous. It can be subversive. Artists throughout the centuries have risked imprisonment and worse for expressing unacceptable ideas. Chinese artist Ai Weiwei is one well-known recent example, but in the last decade, many others have been arrested for upsetting established ideas such as American Spencer Tunick whose art involves photographing crowds of naked people in public places, Indian artist M.F. Husain who went into exile after receiving death threats for his portrayal of Hindu gods and goddesses and Zimbabwean artist Owen Maseko who was arrested for his critical paintings of Robert Mugabe. All this seems a far cry from the almost sanctified auction rooms in major cities where rare art works change hands for ever greater sums.

In the last fifty years, the collecting of fine art has become big business. It has led to the appearance of two art worlds: one in which sincere, committed artists struggle to get their work seen and heard, where academics and press officers write dense texts in support of well-researched and soul-nourishing exhibitions; then there’s the commercial side of the art world in which works by well-known artists are bought and sold for eight figure sums to end up in banks, city halls and the collections of the super-rich.

Art is the planet’s sexiest investment, a realm in which subversion and style are packaged up and sold to the one-percenters. (But that’s not as strange as it may seem. To get really, really rich, and to make really, really good art, both require a spirit of anarchy. Art and those who can afford it are seemingly made for one another.)

This chapter will look at subversive contemporary art in the UK since the 1960s. The last fifty years have been nothing if not interesting. In this time we have witnessed some of the most controversial artworks ever made. Artists have earned furious headlines in the popular press. Homegrown talents, rebels of the art world who are not afraid to challenge the dominant values of their time, have arguably become more famous than any of their indigenous forebears. And we must thank them for transforming Britain from a relative backwater of visual culture into a world leader with a capital to rival New York.

In this chapter we’ll look at the ways in which cutting-edge art became the mainstream and the way cutting-edge artists became the establishment. And we’ll look at how craft became cool, and how, using the web, crafters have created a worldwide movement. Along with the YBAs we’ll look at the Turner Prize and its impact on the nation’s consciousness. And we’ll look at those who make art on the street, and those who live on the social margins. We’ll also explore a traditional art movement, Stuckism, which bucks the trend for idea-based art and demonstrates that figuration and painterliness could be the most defiant qualities around. Finally, we’ll look at the opportunities for difficult artists to find an audience via the web and question the prevalent serious and often lo-fi aesthetic which is emerging with the newest generation of artists.

The current period of austerity in Britain has an intriguing antecedent. As late as the 60s the UK was still emerging from a period of post-war rationing and rubble. Art could go one of two ways: technicolour splendour with the psychedelic movement or the terse cerebral statements made by proponents of conceptual art. The former was drug-induced, music-influenced and utopian. What remains of the latter tend to be the monochrome photos or typeset record cards on which the most serious artists of their age documented their often fleeting actions.

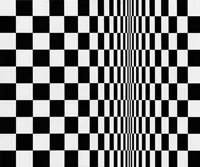

Movement in Squares by Bridget Riley

What’s more, the two movements are roughly sequential, with an explosion of hope in the summer of 1967 followed by disillusion and a more militant approach to art. But although the current landscape owes a great debt to these two countercultural strands, few of the artists are household names. Perhaps only Bridget Riley, whose abstract paintings could well be described as ‘trips’, qualifies as a ‘famous psychedelic artist’. A 1971 appearance at the Old Bailey ensured the editors of the controversial issue of Oz magazine with a certain notoriety, but little lasting glory. Conceptual artists, and their close relations, minimalists, tended to fly under the radar.

Then, as now, however, it took little to bait the mainstream media. Feminism was, in the 1970s, perhaps the most subversive game in town. The ICA drew fire in 1976 by showing a six-part installation by US artist Mary Kelly about the birth of her own child. What irked the tabloids was the inclusion of a series of her young son’s dirty nappies. ‘Post-Partum Document’ took half the decade to make and the results are as cerebral as they are visceral.

In many ways the punk movement was anti-art. For subversion at the end of the 1970s one might find most of it in the growth of zine culture which, thanks to cheap photocopying, took off at the same time as British music got stripped down. The 80s were the last real years of the avant-garde. Academia was ablaze with debates about race, gender, sexuality and AIDS. Given this concern with identity politics it is perhaps no surprise that performance art, including theatre, dance and multimedia became what was called (by People magazine) the decade’s defining art movement. But given that live art is by definition by the few for the few, it is little surprise that by the end of the upwardly mobile 1980s, unless you were buying it, contemporary art in Britain was at its least visible.

Brit Art Hits the World Stage

In the economic upswing of the 1990s, artists were experiencing a moment of cultural confidence that felt both very new and very reassuring. Artists were taking control of their own careers, but doing so in the spirit of 1970s punk or the upwardly mobile 1980s: the DIY ethic and entrepreneurial streak of Brit art in the 1990s was a blend of the underground and a Thatcherite love of private enterprise. And like the Pistols at the 100 Club, there was one show which came to embody the zeitgeist. The name was ‘Freeze’ in 1988 and the venue was a warehouse not a gallery – the kind of place we had come to expect a rave, rather than an exhibition. The impresario, meanwhile, was an undergraduate called Damien Hirst. ‘Freeze’ was to hijack the art world’s imagination and send a fleet of cabs to ferry the capital’s influencers to the Docklands. Charles Saatchi came, notoriously set the precedent for buying work from Young British Artists, and a movement was born.

This was no longer the dead serious conceptualism of the 1970s. This was the overheated market-driven 1980s. If there was one creative endeavour in which we led the world it was advertising. And so an adman would push up and build demand for the most market-friendly generation of artists the world had so far seen. A businessman, albeit a highly creative one, rather than a critic or curator, was in the driving seat of art history, as Charles Saatchi liaised with the Royal Academy to stage a blockbuster exhibition of these new artists in 1997. ‘Sensation’, a word the former copywriter may have once used to describe, say, a soft drink, was now the byword for a group of artists so controversial they bordered on the offensive.

That show did what it said on the tin and the tabloid press, who once ignored art, wrote outrage pieces about Marcus Harvey’s portrait of Myra Hindley (overleaf), painted entirely in child’s hand prints and the equally disturbing child mannequins by Jake and Dinos Chapman, which traded noses for penises, mouths for anuses. It was a long way from, say, Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Myra Hindley by Marcus Harvey

By the time ‘Sensation’ was launched the Chapman Brothers and Tracey Emin had been brought into the fold. The number of great careers this show launched is remarkable. Some criticised the RA’s seal of approval, for what they saw as canny marketing by Saatchi. But we should remember that the collector has opened doors to the public for free in three different venues since 1985 and in 2010 tried to gift his £30 million collection to the nation. Saatchi also gets credit for helping to bring to life one of the most iconic artworks of the 20th century; Damien Hirst’s formaldehyde shark began life as an expensive doodle on the back of his proverbial fag packet. (But note: ‘The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living’ might have frightened a few children, but it will never pose a challenge to the state.)

YBA Dissent: More Than Just a Pose?

Though many were quick to judge the new Brit artists as attention seeking, celebrity hungry and lacking serious intent, there was still a certain political aspect to the YBA movement. 1997 saw the election of the first Labour government in eighteen years. Fashion, music and art came together in a way which enhanced British industry. Pop stars were invited to Number 10 and our headline-grabbing artists were hitched to the Cool Britannia brand. It was the first and perhaps last time a UK government would manage to co-opt what was still essentially a rebellious practice. Such was the importance of art to our national identity that money was found to build the Tate Modern (£134m) and London became the capital of the art world, with a number of young turks (including Gavin Turk) as the darlings of a global art media. And to think British art was once on the staid side. It is all too easy to believe a tale in which Sir Winston Churchill said he would ‘kick Picasso up the arse’. It would have astounded the great statesman to come across Tracey Emin’s unmade bed.

My Bed by Tracey Emin, at the Tate Gallery

But it wasn’t solely through political association that the movement was influential. It inspired other artists, outside their studios, not just in terms of the content of their work. Cliff Lauson, co-curator of the 2011 Tracey Emin retrospective at the Hayward Gallery, London, weighs up the legacy of the YBAs. ‘I think a number of the YBAs were quite subversive in the sense that they came from nowhere,’1 he says. ‘They were enterprising and established their own careers rather than depending upon the art establishment to accept them.’ He describes this as a kind of ‘institutional subversion,’ which is quite different from the political or artistic variety, in that the focus was on rejecting the traditional means of establishing yourself as an artist. These were the times to get an agent or a gallery to represent you, and target the major London galleries as the ‘be-all-and-end-all’. These emerging rebels of the art world stuck two fingers up at the art establishment and made their own rules.

Old Hands Cash In, New Talent Emerges

In the coming decade, the market would continue to throw up surprises. Damien Hirst bought back all his work from Saatchi in 2003 and in 2008 cut the dealers out of the loop by selling direct to his buyers with an auction at Sotheby’s. This was at once highly independent and ‘therefore hip’, and also deeply in bed with worldwide collectors. Hirst has said he makes art with whatever he finds at hand and in 2007, it was money which surrounded him as he brought a £50 million diamond encrusted skull into the world. UK art’s enfant terrible had just made the most expensive artwork of all time. It was radical, but not quite right. Sensing he could go no further in this direction, Hirst returned to painting in 2009 with a show at the Wallace Collection. It came under fire from many critics who questioned whether it was his fame rather than his talent for painting that had secured the show.

For the Love of God by Damien Hirst

Tracey Emin, meanwhile, was canny enough to maintain a drawing practice. In 2011 she was made Professor of Drawing at the RA. Works on paper and embroidery have underpinned the Margate artist’s career and put the seal on her 2011 retrospective at the Hayward Gallery. In 2012, Damien Hirst, who once said he’d never show at the Tate, did just that. In the year London hosted the Olympic Games, the city swung like it was 1997 all over again; the cultural Olympiad, which brought art to the rest of the UK, spelled a coming of age for a dynamic contemporary art scene which began back in the late 1980s.

But as artists got richer and more professional, the next wave made an attempt to kick against that. A new craft sensibility came to the fore following the millennium. And the Turner Prize threw up a shock result when it gave the 2003 award to a man best known for pottery, albeit vases with detailed and angst-ridden political decoration. Grayson Perry, also a cross dresser, picked up his £25,000 cheque with the words: ‘It’s about time that a transvestite potter won.’ As it frequently seems in the art world, anything seemed possible. And the UK media found a new British eccentric as Perry and his garish frocks appeared on prime-time TV. In 2013 he was widely celebrated for delivering cogent and accessible Reith lectures on Radio 4. His transition from rank outsider to national treasure seems to have been completed in no time. That’s how fast the art world, and the media, can absorb a foreign body and, if we’re being cynical, neutralise its threat.

My Heroes by Grayson Perry

Art Party Conference Says ‘No!’ to Tuition Fees

Thanks in part to Perry, there’s plenty of craft to be found in the art world today. His fellow Royal Academician, Bob and Roberta Smith, is, despite the confusing name, a down to earth sloganeer and a sign-writer. It could be said he’s an agitator, which gives a certain tension to his august position at the RA. He too has a performative persona whose work blends the personal and political. In 2013, with the help of funding from DACS,2 the CASS3 and the Art Fund,4 he established the Art Party Conference in Scarborough: a timely response to the hike in tuition fees at art school. Publi...

Table of contents

- Counterculture UK – a celebration

- About the Editors

- Copyright

- Title

- Images

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Art

- 2. Black and Minority Ethnic Arts

- 3. Comedy

- 4. Dance

- 5. Disability Arts and Activism

- 6. Environmentalism

- 7. Feminism

- 8-i. Film: Beyond the Mainstream

- 8-ii. Subversive Cinema

- 9. Gaming and the Internet

- 10. LGBT Culture

- 11. Literature

- 13. Music

- 12. Negative Space

- 14. Theatre

- 15. YouTube and Social Media

- Endnotes

- Index