- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

A complete examination of the men and forces that created and shaped the modern state of Israel over the last hundred years

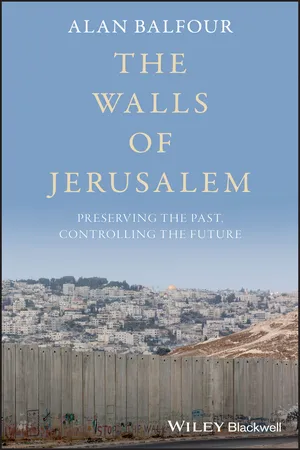

Walls of Jerusalem is a study of the creation and evolution of the modern state of Israel. This unique work begins with the actions of four extraordinary men — Theodor Herzl, Chaim Weizmann, Ze'ev Jabotinsky, and David Ben-Gurion — and follows with their influence on subsequent leaders and on the political and military decisions that have shaped and changed Jerusalem and the nation. The resulting physical realty has made concrete the shift in vison from the broad utopian ideals of the beginning, to the separation barrier and settlement enclaves that increasingly divide both Jewish and Palestinian cultures.

The author traveled across the West Bank, into the Israeli settlements and along the Israeli security barrier dividing Israel from Palestine. He entered the tombs, mosques and synagogues, experienced the distortion of Jerusalem since the building of the separation barrier - the watchtowers, the welded gates, the shuttered shops, divided highways and back-ways, tunnels, bridges, checkpoints, to better understand evolving reality that defines the stage for the future relationship between Israel and Palestine.

Walls of Jerusalem is a timely book, its vivid narrative journeys through a century and a half of dreams and conflicts that lead to a divided Jerusalem:

- It presents each stage of Israel's evolution, from the 1896 publication of Herzl's Der Judenstaat and the Balfour Declaration, to the opening of the United States embassy in Jerusalem in 2018

- Relates the visions of Israel's creators to the destructive and constructive forces utilized to create a new nation

- Reviews the century long attempts by international organizations to resolve the conflict between Jews and Palestinians

- Makes every effort to present a balanced exploration of challenges facing the state of Israel and its place on the world stage, but in conclusion gives emphasis to the plight of the Palestinians

- Integrates illustrations with text to provide a detailed portrait of central figures in modern Israel's history

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Herzl, Weizmann and the Balfour Declaration

If you will it, it is no dream;and if you do not will it,a dream it isand a dream it will stay.Herzl

We have made it a rule not to say too much, except to those … we trust … the goal is to revive our nation on its land … if only we succeed in increasing our numbers here until we are the majority…

There are now only five hundred [thousand] Arabs, who are not very strong, and from whom we shall easily take away the country if only we do it...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Prologue

- 1 Herzl, Weizmann and the Balfour Declaration

- 2 Jabotinsky, Ben‐Gurion and the Iron Wall

- 3 “National Homeland”

- 4 Al‐Nakba (Catastrophe)

- 5 Eretz Yisrael

- 6 Settlements

- 7 The “Separation Barrier”

- 8 In Palestine

- 9 Netanyahu, Trump and the Future

- Epilogue

- Index

- End User License Agreement

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app