eBook - ePub

A Companion to the Archaeology of the Roman Republic

Jane DeRose Evans, Jane DeRose Evans

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

A Companion to the Archaeology of the Roman Republic

Jane DeRose Evans, Jane DeRose Evans

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

A Companion to the Archaeology of the Roman Republic offers a diversity of perspectives to explore how differing approaches and methodologies can contribute to a greater understanding of the formation of the Roman Republic.

- Brings together the experiences and ideas of archaeologists from around the world, with multiple backgrounds and areas of interest

- Offers a vibrant exploration of the ways in which archaeological methods can be used to explore different elements of the Roman Republican period

- Demonstrates that the Republic was not formed in a vacuum, but was influenced by non-Latin-speaking cultures from throughout the Mediterranean region

- Enables archaeological thinking in this area to be made accessible both to a more general audience and as a valuable addition to existing discourse

- Investigates the archaeology of the Roman Republican period with reference to material culture, landscape, technology, identity and empire

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist A Companion to the Archaeology of the Roman Republic als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu A Companion to the Archaeology of the Roman Republic von Jane DeRose Evans, Jane DeRose Evans im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Literatur & Antike & klassische Literaturkritik. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

PART I

Material Culture and Its Impact on Social Configuration

CHAPTER 1

Development of Baths and Public Bathing during the Roman Republic

1 Introduction

Material remains of baths – basins, pools, terracotta, stone and metal tubs – and well-developed hydraulic systems found in Crete, Cyprus and Anatolia, such as the second millennium palaces at Knossos, Boğazköy and Zincirli, attest to the remarkable degree of technical and aesthetic sophistication attained in bathing, at least by the privileged classes of Bronze Age civilizations (Naumann, 1971: 195, 442–3; Lloyd, 1967: 78–9). Looking back to the legendary past, in Homer’s world bathing in warm water was a luxurious and refreshing experience, a special reward reserved for heroes at the end of a trip or battle. In the Iliad men who returned from reconnaissance “washed away in the sea the thick sweat from their skins and necks” (Il. 10.572), and as retold by Athenaeus centuries later, after having this way refreshed themselves “they went to the polished tubs and bathed, smearing themselves with oil, they sat down to their meal” (Deipnosophistae 1.24 d, trans. C. Gulick, 1927, Loeb). In these aristocratic contexts hot bathing was a fairly simple matter of washing from a cauldron of hot water mixed with cold to comfortable warmth. However, already in the fifth century the conservative view in Greece criticized hot, pleasure bathing as a sign of decadence and aspired towards the frugal lifestyle of the Spartans, who supposedly only bathed in cold water (“Laconian style”).

Among the ancient Mediterranean civilizations, Romans deserve to be singled out in their extraordinary devotion to bathing as a social and recreational activity deeply rooted in daily life. Bathing in public was a central event in Roman culture and a very important part of the Roman day. Demonstrating little interest in cold water bathing (unless it was a medical recommendation), Romans developed and perfected the heating and water supply technologies of baths, which changed bathing from a simple act of hygiene to one of pleasure. For the average Roman, who spent a considerable part of the day in the public baths, bathing was an activity which incorporated sports, games, massage, body culture and relaxation much like a social club or community center. Some of the larger baths even included quasi-intellectual facilities such as libraries and lecture halls as well as colonnades, galleries and exedrae for the exhibition of works of art. Roman baths embodied the ideal of Roman urban living. By the Late Republic, Rome had nearly 200 small baths as recorded in urban census documents (Notitia Romae (Notitia regionem urbis), ca. 334–57 CE and Curiosum urbis Romae, ca. 357–403 CE). By the end of the fourth century CE their numbers had swelled to a staggering 856, plus ten or eleven Imperial thermae, which were exceptionally large and luxurious bathing complexes ordinarily owned and operated by the state.

What accounts for the obvious delight Romans had in their baths and the intense popularity of public bathing? There is no simple and definite answer to this question. One overarching observation is that bathing was popular simply because it had become a habit. It had become a comforting part of urban life and national identity – and the more Romans liked bathing the more likeable it became. Not to bathe would have been un-Roman. Still, why did bathing become a daily habit in the first place?

2 Bathing as Pleasure

We believe that among the most important reasons for the popularity of bathing is the pleasure factor: bathing is a physically and psychologically pleasing activity that relaxes the body and soothes the mind. The bathing experience – warm, clean water, shining smooth marble surfaces, steamy atmosphere, the aroma of perfumed ointments, the nudity and intimacy of massage – awakened the senses and created a state of comfort and well-being the Romans called “voluptas.” A freshly bathed person felt light and optimistic. These sensory pleasures were admired aspects of baths and bathing. A fifth-century CE dedicatory inscription from a bath in Serdjilla, in Syria, is one of many that announced that the bath could bring “comfort and happiness” to the entire village (Prentice, 1901). The renovated Baths of Faustina in Miletus, in Asia Minor, were described as an “ornament” to the city where the citizens enjoying the delights provided by the refreshing bath waters “all are relieved of toils and labor” (Gerkan and Krischen, 1928: no. 339). Often these waters and their delights were identified with nymphs and charites (Graces), minor goddesses that protected the waters and personified beauty and charm.

3 Bathing as Luxury

Enhancing the sense of pleasure and delight was the sumptuous material world created by public baths. As observed by Cicero, in the first half of the first century, Romans disliked private luxuries but “delighted in public magnificence” (Mur. 76). The interiors of baths, decorated in fine polychromatic marbles, intricate mosaics, stucco ornament, gleaming bronze hardware and marble statuary, all under high and well-lit vaults and domes, were perhaps the most appropriate candidates for such public display of wealth and luxury. And this was a luxury that could be enjoyed by all, or almost all. Wealth in private life was for the enjoyment of the privileged few; public baths, dubbed as “people’s palaces,” brought this bounty to the masses. As a rule even baths run as lucrative enterprises which charged a fee were not outside middle-class affordability. There were, however, a few like the Baths of Etruscus in Rome which must have been a small but exclusive establishment with a select clientele. Martial recommended it to a friend admiringly: “If you do not bathe in the thermulae (small bath) of Etruscus, you will die unbathed!” (Epigrams 6.42, trans. W. Ker, 1968, Loeb; see also Stat. Silv. 1.5). The world of material magnificence offered by public baths, especially the great thermae of the Imperial period, afforded urban populations the opportunity to escape their overcrowded and cramped living conditions and the dusty streets for a few hours a day and bathe in style. For a few hours a day the privilege of public bathing took the individual out of his shell and gave him a place among others. But most importantly, it gave him an opportunity to share the empire’s wealth and, perhaps, to believe in its ideologies.

4 Bathing and Ancient Medicine

An important and practical explanation for the popularity of baths is medical: bathing was believed to be good for health and particular forms of bathing were recommended as cures for particular ailments. In a world that lacked the modern means of diagnosis and cure, where almost every surgical intervention risked the patient’s life, it is logical that preventive medicine, as represented by thermal and curative bathing and which aimed to maintain a healthy body, was far preferred to drastic and intrusive methods of treatment (Yegül, 1992: 352–5; Fagan, 1999: 85–103).

Bathing as a therapeutic measure received its initial authority from the recommendations of the Hippocratic School of Greek medicine in the fifth century. These recommendations, often promulgated by itinerant doctors and popular medical lecturers, were largely based on empirical and sometimes inconsistent assumptions. According to the Regimen in Health and Regimen in Acute Diseases, the two fundamental treatises of the Hippocratic corpus, one should bathe more frequently in the summer than in the winter; fresh water bathing moistens and cools the body while salt (sea) bathing dries and warms it up. Bathing was not recommended in cases of strong fevers or for those suffering from diarrhea or constipation. If not taken the right way bathing could actually harm the person, but “if preparations are satisfactory and the patient welcomes the idea, a bath should be taken every day” (Acute Diseases, trans. in Lloyd et al., 1978: 205; cf. 186–206, 272–7; see also Vallance, 1996). It is interesting to note that the Roman habit of daily bathing seems to have its roots in the recommendations of Greek medicine as do the customary exercises as a prelude to baths.

According to Diocles of Carystus, a famed physician and dietician of the fourth century, an ideal daily routine included a relentless series of morning and afternoon exercises, massage and bathing (Jaeger, 1938). The views and practices on exercise and bathing for health were introduced to the Roman world through the works of various Hellenistic writers. Of particular significance is Asclepiades of Prusa (Bursa, Turkey), a Greek physician who practiced in Rome at the end of the second and the beginning of the first century (Green, 1955). This was just the period when bathing in public was making significant gains in Rome and Italy with concomitant development of baths and heating technology. Asclepiades employed a strict program of diet, exercise and baths and included cold water bathing in his regimen. His most influential followers, who established exercise and bathing as a quasi-scientific method, were Celsus, a medical writer of the first half of the first century CE, and Galen, a doctor from Pergamon and a physician who achieved great success in Rome during the second half of the second century CE. Both of these influential sources emphasized the benefits of hydrotherapy by specifying the nature and extent of bathing in an easy-to-understand style and in considerable detail. In treating a wide variety of maladies, they recommended bathing in close association with physical exercise, massage and sweating – activities that constitute the core of the Roman bathing routine.

It is also interesting to note that the explicit programs of bathing outlined by Galen involved a progression from cold to lukewarm to hot areas; he also recommended sweating and massage and a final plunge into the cold pool (to close the pores of the skin, to brace and energize the body). This progression roughly coincides with the tepidarium, caldarium, laconicum and frigidarium of the Roman baths already reflected in the architectural order and plan of many Republican establishments. Although we do not know to what extent the patients or the general public followed such a strict therapeutic regimen, it appears logical to assume that both thermo-mineral and regular city baths were used for curative purposes. Public baths were better equipped for treatment since even the better houses did not have elaborate bathing facilities. Nor could one get at home the professional attendants and health technicians necessary to administer the bath correctly. These points had been emphasized already in the Hippocratic corpus: “The basin should afford easy getting in and out. The patient should remain quiet and passive during the process of curative bathing; he should not attempt to wash himself, but let others do it for him” (trans. in G. Lloyd et al., 1978: 204–5).

5 Bathing Ritual and Activities

Bathing as a social ritual occupied the larger part of the afternoon. Martial recommends the “eighth hour” (ca. 2–3 p.m.) as the best time for bathing when the heat of the baths was tempered (Epigrams 10.48). Since the Roman day was divided into 12 hours from sunset to sunrise (midday was the sixth hour), the length of the hours and the time to bathe varied from season to season. Patrons spent several hours in the baths, which in the shorter winter days might have necessitated artificial illumination (and explains the large number of lamps found in some bath excavations), but as a rule night bathing was rare and considered unsafe. Bathing was also enjoyed more in brightly lit interiors.

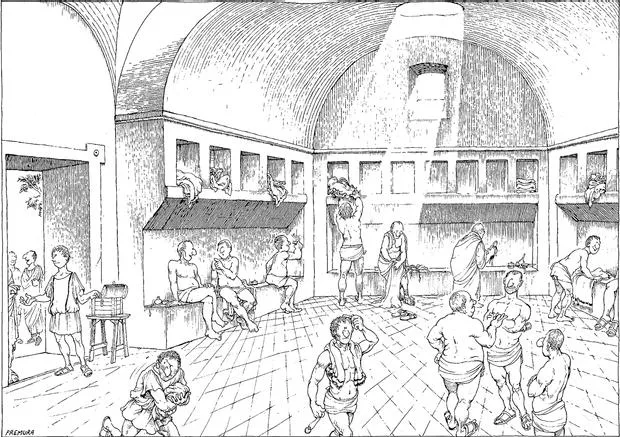

The essentials and basic routine of bathing as stated by Pliny the Younger appears simple: “I am oiled, I take my exercise, I have my bath” (Ep. 9.36). A wealthy person was accompanied to his bath by his servants and slaves carrying his towels, bathing garments and toilet kit; a poor person carried his own bundles. Upon arriving at the baths, one undressed usually in a special room reserved for this purpose called the apodyterium, which in some of the Republican era baths was characterized by rows of small cubby-holes to hold clothes (Figure 1.1). Putting on a short tunic, patrons normally engaged in some kind of physical exercise in an open courtyard or palaestra. It would be misleading, however, to imagine that the average Roman undertook a strenuous workout like the young athletes of the Greek gymnasium. Roman gymnastics in the context of bathing were often light, such as the numerous ball games intended to loosen the muscles and build up sweat – activities that appealed to all age groups and body shapes. Martial mentions no less than five different ball games for the palaestra. One, called “triple ball” (pila trigonalis) was, as the name implies, a game for three where the opponents stood roughly at the three points of a triangle and tried to confuse each other by passing several balls back and forth (Epigrams 12.82, 14.46, 4.19, 7.32). Among other palaestral sports, running, boxing and wrestling are mentioned but their practice was not restricted to the open-air courtyard; many of the larger baths (especially of the Imperial period) had special halls (basilica thermarum; see below) that could be used for indoor athletics. Women did participate in sports and games, though they probably preferred the lighter variety. Swimming was also a popular bath exercise but it is unlikely that any serious or competitive swimming or diving was done. With few exceptions, such as the deep lap-pool of the military baths at Isca (Caerleon, Wales; see below), even the large swimming pools, the natationes, of the thermae only reached a depth over 1.0 to 1.20 m. Most of the bathers must have enjoyed a few easy strokes, leisurely wading and splashing. The easy and inclusive nature of sports welcomed even the elderly and the less athletically inclined to participate and made the public baths a pleasure for the masses.

Figure 1.1 Reconstruction of a typical apodyterium in use in the Late Republican period. Source: Pasquinucci (1988: fig. 24). Drawing by A. Fremura. Used by permission of Franco Cosimo Panini Editore.

Time spent in the palaestra was pleasant but few were so enthused with their exercise as not to drop everything and hurry inside when the tintinnabulum, the bell that announced the opening of the hot baths, sounded. Inside, the general order of bathing required a movement from warm to hot through a number of intercommunication rooms at varying degrees of warmth. Some bathers also spent time in one of the special rooms for sweating – the laconicum for dry heat and the sudatorium for steamy, wet heat – but identification of these spaces in actual baths is difficult. Bathing terminated in a cold plunge in one of the pools of the frigidarium. Some of the larger baths even had special sun rooms (heliocamini) with large, unglazed windows oriented west or south-west and unpaved, sand-covered floors. It must have been a pleasant experience to pretend to be at the beach and enjoy broad views across land and sea while sunbathing or immersed in a pool.

Among the most engaging of the plethora of social activities in the baths must have been the pleasure of being with friends, conversation and gossip, while perhaps enjoying a relaxing massage. Poetry reading, music and singing – not always welcome – were common. There were professional performers, too – jugglers, animal trainers, conjurors, jesters, mimes and gymnasts. Also pleasurable, at least for some, was eating and drinking, which would have added merriment to any group. A price list scribbled on a wall in the Suburban Baths in Herculaneum includes for sale “nuts, drinks, hog’s feet, bread, meat and sausage” (CIL IV.10674). Vendors of food and drink could be found in any bath, but in Magnesia-on-the-Meander, there was a restaurant annexed to the bath which offered cheese, barley, olives, wine, fish, vegetables and a kind of “lyre-shaped” pretzel (Cousin and Deschamps, 1888: 203). The pastime engaged in the baths was supposed to be a light snack, a prelude to dinner proper, an important social event culminating the day, often taken in the company of others. Martial was a cordial host who strove to arrange a fine dinner for his bathing friends: “You will dine nicely, Julius Cerialis, at my house. You will be able to observe the eighth hour [time for bathing]; we will first bathe together at Stephanus’ Baths … [then at dinner] there will be lettuce for relaxing the bowels …” followed by a long list of delectable treats (Epigrams, 11.52, trans. W. Ker, 1968, Loeb). A good bath called for a good dinner and public baths were the best places to invite somebody, or to get an invitation at a well-appointed household with a cook famed for his culinary skills. As mockingly narrated by Martial (Epigrams 2.14), some luckless characters, in order to avoid the social disgrace of dining alone, moved from one bath to another until they secured an invitation.

6 Ethical and Moral Concerns and Criticism of Roman Baths

Since ethical and moral concerns persisted as a topos of Roman literature, it is not surprising that baths with their luxurious and hedonistic world provided a likely subject for criticism. Their permissive and populist atmosphere could easily tolerate, or even encourage, coarse, irritating and occasionally violent behavior. The tramp, the vagabond and the ordinary lout found excellent opportunities for uncouth and boorish ways. The newly rich showed off their wealth; the half-educated subjected their victims to their grandiose literary ambitions; thieves and tricksters circled the crowd.

Seneca, a conservative writer and philosopher who lived in the first half of the first century CE, compared the well-lighted baths of his day with the dark and austere interiors of old ones, such as the one reputedly used by Scipio Africanus, the hero of the Punic Wars:

[Today] we think ourselves poor and mean if the walls [of our baths] are not resplendent with large and costly mirrors [made of white polished marble]; if our marbles from faraway Alexandria are not set off by rich mosaics of rich, yellow stone from Numidia [giallo antico, an expensive marble] … if our vaulted ceilings are not buried in glass [mosaics]; if our swimming pools are not lined with marble from Thasos, once a rare and wonderful sight in any temple … What a vast number of statues, of columns that support nothing but are built for mere decoration … Our ancestors did not think that one could have a hot bath except in darkness.

(Ep. 86, trans. R. Gummer, 1962, Loeb)

Taken at fac...

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Cover

- Series page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- List of Illustrations

- Notes on Contributors

- Abbreviations

- Preface

- Introduction

- PART I: Material Culture and Its Impact on Social Configuration

- PART II: Archaeology and the Landscape

- PART III: Archaeology and Ancient Technology

- PART IV: The Archaeology of Identity

- PART V: The Archaeology of Empire during the Republic

- PART VI: Republican Archaeology and the Twenty-First Century

- References

- Index

Zitierstile für A Companion to the Archaeology of the Roman Republic

APA 6 Citation

Evans, J. D. (2013). A Companion to the Archaeology of the Roman Republic (1st ed.). Wiley. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1002027/a-companion-to-the-archaeology-of-the-roman-republic-pdf (Original work published 2013)

Chicago Citation

Evans, Jane DeRose. (2013) 2013. A Companion to the Archaeology of the Roman Republic. 1st ed. Wiley. https://www.perlego.com/book/1002027/a-companion-to-the-archaeology-of-the-roman-republic-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Evans, J. D. (2013) A Companion to the Archaeology of the Roman Republic. 1st edn. Wiley. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1002027/a-companion-to-the-archaeology-of-the-roman-republic-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Evans, Jane DeRose. A Companion to the Archaeology of the Roman Republic. 1st ed. Wiley, 2013. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.