![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to Pesticide Regulation

There was a time, not so long ago, when all a pesticide applicator had to do was read a product's label to know how to apply it safely and what shouldn't be done with it.

Those days are gone. While the pesticide label is still considered the law by federal and state pesticide regulators, much more of the burden for knowing new rules and regulations is being placed on the applicator.

Understanding and interpreting complex and sometimes booklet-length pesticide labels has never been easy.

But now new federal programs to protect endangered species and groundwater from pesticide contamination will require users to go to a pesticide dealer or Cooperative Extension advisor to find out how to comply.

And in many communities, the local city or county government has added another layer of regulation by requiring signs and other notification of applications.

Meanwhile, there is a trend toward requiring applicators to be better trained before they can go out into the field. At the same time, legislators are interested in expanding the universe of people who need to be certified to use restricteduse pesticides, a list that grows longer all the time. And state governments are moving toward requiring certification of people who use all pesticides for a living, not just the restricted ones.

What all this means is that following the rules is no longer a simple matter of reading a label, a task that in itself has never been easy and isn't likely to get easier anytime soon.

More and more these days, it's up to the pesticide user to pay close attention to what's legal and what's not.

Pesticide users themselves are getting more diverse. About 70 percent of pesticides sold in the United States are used for the production of food, including that produced in greenhouses. The rest are used for structural pest control, by landscape gardeners, golf course superintendents, park maintenance workers and public health specialists who kill mosquitos or other disease-bearing bugs.

Traditionally, regulators have kept their focus mainly on farmers because they were using most of the pesticides. But other users are getting more scrutiny these days, such as lawn care companies. That's because there is public concern about the chemicals placed on their or their neighbors lawns.

Also, given the pesticide-of-the-week syndrome, there's no telling when the next chemical or applicator group will be under fire.

So, now more than ever, it's important that applicators of all kinds of pesticides in all kinds of settings be aware of the regulatory system they work under and what motivates it. That makes it easier to be safe, be prepared for the next crisis, and be able to tell customers or other members of the public how pesticides are tested and controlled in this country.

This volume will attempt to paint in broad national terms the kind of regulatory issues coming down the pike. It will also give a brief overview of the federal pesticides law, how it works and how the states carry out its mandates.

There are results from a first-ever 50-state survey of state certification and training regulations. It shows that state programs vary widely in terms of who must be certified and how much they have to know to do so.

Following that is a description of California's pesticide regulatory program, which many believe is the most comprehensive and stringent in the world and the model for what many other states would like to do in the future.

Another chapter talks about why the public is so concerned about pesticide use, and how that drives politicians to write more laws. But it also points out some poisoning incidents that prove there's some substance behind all the worry.

This book also briefly addresses the scientific and technical issues involved in the safety of pesticides, to give you a sense of why these issues often become mired down in talk of parts per million. Often the scientists themselves can't agree about what's risk and what's not.

There's also a chapter on labels: an example of one and some pointers about how to read one and how to recognize symptoms of pesticide poisoning.

We also talked to a few of the people involved in pesticide regulation and offer their thoughts on some of the issues confronting pesticide users these days.

Finally, there's a list of who to contact in your state to get started on the certification process or to get more information about a regulation mentioned here.

It is hoped that this volume will provide some valuable background and context for people facing the increasingly complex world of pesticide regulation

![]()

Chapter 2

The System

Pesticides are regulated under a system in which the federal government makes sure pesticides themselves are safe to use, while state governments make sure applicators are trained and actually use the chemicals properly.

This was set up under a 1972 law called the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act. The first pesticide law was actually put in place in 1910, but all it did was attempt to ensure that consumers got pesticides that actually worked.

The law has been changed a number of times, each time making it a little bit more comprehensive and stringent.

For instance, in 1948 it was expanded to register and label products and require that they include safety warnings. The law wasn't especially stringent, though, because a manufacturer could market its product even if the U.S. Department of Agriculture (which was then in charge of pesticide regulation) turned down the registration.

It wasn't until 1972, a big year for new environmental laws, that Congress started looking at pesticides as a safety risk. That's when FIFRA was substantially rewritten to set up a system in which the new Environmental Protection Agency would take over regulation of pesticides and make sure the benefits of using these chemicals outweighed the health and environmental risks.

The law was also rewritten twice during the 1980s to update the scientific data on the health and safety of pesticides that had already been registered over the years, but we'll get to that later.

Basically, FIFRA regulates pesticides by stating that no such chemical can be used in the United States without being registered with the federal government. It uses the term "pesticide" universally, to include anything that kills bugs, plants, fungus or anything else. The actual definition says a pesticide is a substance or mixture of substances intended for preventing, destroying, repelling or mitigating any pest, or intended for use as a plant regulator, defoliant or dessicant.

The law defines a pest as an undesirable insect, rodent, nematode, fungus, weed or any other form of terrestrial or aquatic plant or animal life or virus, bacteria or other microorganism.

Registration and Reregistration

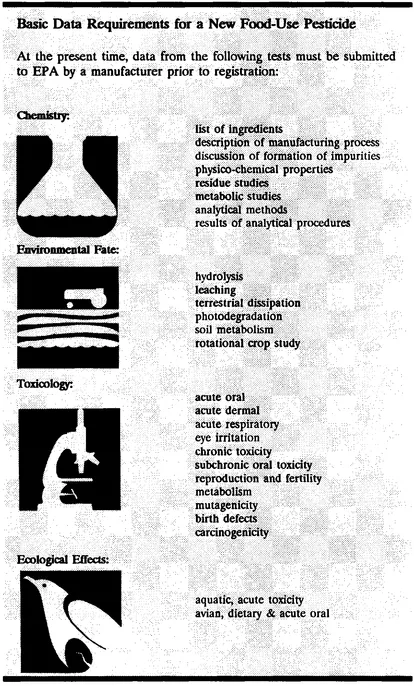

Pesticide manufacturers must go through a lengthy process not only to create their products in the laboratory, but to test them thoroughly and jump through EPA's regulatory hoops to get a product registered.

Most of the 20,000 pesticide products now on the market were rirst tested and registered 20 or 30 years ago. The industry estimates it would take $10 to

$30 million and 5 to 7 years to get a new pesticide on the market now.

The EPA has a whole battery of tests that are required before a product can be "registered" as a pesticide that can be used in the United States. Among the tests are toxicology — whether the product harms the body in an acute, or immediate way; these tests are usually done on laboratory rats and mice, although sometimes they are conducted with dogs or monkeys.

There are also cancer tests, also involving animals, and in some cases environmental tests to see if the product would harm birds, fish or any other part of ecosystems.

The EPA is moving toward requiring additional tests called neurotoxicity tests that determine whether a chemical causes nervous system problems. So far, only certain classes of chemicals known to prompt blurred vision, headaches and other problems have had to undergo those tests; EPA eventually wants all pesticides, new and old, to undergo them. One problem has been that the symptoms of neurotoxicity are so subjective: how do you know if a rat has a headache? Science marches on.

One complaint the industry has had about all these tests is that the standards change constantly. For instance, the first pesticides to undergo these requirements in the early 1970s were tested using the current scientific methods of the day. But now, science has moved along so quickly that those tests are no longer considered scientifically valid. Perhaps the laboratory workers didn't use enough mice, or they didn't take detailed notes or — in the case of one highly controversial chemical, they used vegetable oil to administer the chemical to mice, and the oil has since been shown to alter the test results.

That's what reregistration is all about. All the 20,000 different pesticide products — containing more than 700 different active ingredients — that were tested using 1970s technology are now obsolete and have to be retested at a cost of millions of dollars to their manufacturers.

Most pesticide makers don't complain too much about the fact that reregistration exists — they figure it's worth it to keep the public satisfied that their products are safe. But they are frustrated with the idea that, conceivably, once this set of testing is done (hopefully sometime in the 1990s), will it all have to be done again according to 21st century standards?

EPA officials acknowledge they don't have an answer. At this point, however, they're just trying to get through the reregistration process that Congress required EPA to begin in 1978 and to hurry up with in 1988.

EPA has been trying to get the work done for years, but has been stymied by lack of manpower, cut during the Reagan years, and changing scientific standards.

Critics argue that EPA's real problems were more bureaucratic in nature: computer systems that weren't up to handling that much material; constant turnover in the federal government that meant new people had to be trained to review the tests according to the pesticide program's arcane standards; and just the basic inertia that sets in at any large agency where no one is really accountable for the results.

Whatever the reasons, the hurry-up law passed by Congress in 1988 was supposed to help some of those problems. Congress threw some more money at EPA and gave it some strict deadlines to require companies to do the testing or lose their registrations, and to review the paperwork and make some decisions.

As the bill was being signed, EPA had completed three reregistrations out of nearly 700 active ingredients, and was told by Congress to be done with all of them by 1997.

At the beginning of 1993, EPA had a grand total of 28 done. At that pace, EPA officials acknowledged, there's no way they can get done by a 1997 deadline.

Complicating matters is the fact that a frighteningly large percentage of the tests being conducted to fulfill the new requirements weren't acceptable — they just didn't meet EPA's standards for a well conducted test.

EPA is expected to go before Congress and ask for more money to hire people to go through the huge pile of tests. Officials will probably ask for reregistration fees — paid by manufacturers — to be increased.

Even if the official review of many pesticides isn't done, the reregistration program has had a definite impact on the marketplace.

Products are likely to disappear as manufacturers drop pesticides that just aren't worth the cost of additional tests. Of the 613 ingredients identified by EPA as needing to be reregistered, 379 of them have had a manufacturer or group of makers agree to do the testing. Another 206 have not.

Big-ticket items like Roundup aren't about to go by the wayside. But growers of specialty items, called minor crops, began to lose products designed specifically for them.

That has caused considerable concern among those growers and prompted Congress to consider ways to get the studies done by someone other than the manufacturer or to get EPA to relax its standards for certain low-risk minor use pesticides.

According to a June 1992 General Accounting Office report on the problem, more than 40 percent of the nation's $70 billion agricultural sales were from minor crops — vegetables, fruits, nuts and ornamentals.

The GAO found that a government program set up to conduct tests to save important minor use pesticides was seriously underfunded and that the U.S. Department of Agriculture wasn't doing much about it. Ultimately, Congress will be asked to make this pesticide research money a priority at the same time it is trying to reduce the federal budget deficit.

Other FIFRA Provisions

Besides registering pesticides, the other major feature of the FIFRA is the emphasis put on the label. EPA likes to say "the label is the law." That means it is illegal to do anything that is prohibited on a pesticide label. That makes some pesticide labels amazingly long — they actually turn into booklets. They explain the potential health effects of the product, how to use it safely, whether to wear protective gear when using it, when it's safe to go back into a field, etc.

One of the key things to look for on a pesticide label is whether the product is registered for "re...