![]()

1

Introduction: Common Land as a Contested Resource

Over 500,000ha of common land survive in England and Wales,1 the vast majority consisting of marginal land beyond the limits of cultivation, characteristically clothed in semi-natural vegetation. Commons include large tracts of the mountains, hills and moorlands of upland England and Wales, the sandy heaths and wetlands of lowland England, and open spaces on the margins of settlements, from the large metropolitan commons around London to small patches of rough ground on the edges of villages (Hoskins and Stamp, 1963, pp104–110, 134–136; Everitt, 2000). Today, they fulfil a range of roles: many continue to serve a function in the agricultural economy as grazing grounds; most are important as open spaces for recreation; in ecological terms, many are deemed to be fragile environments with a high conservation value; some serve particular purposes – for example, as grouse moor or for military training. Historically, these ‘wastes’, as they were termed, formed an integral part of the traditional rural economy, not only as grazing for livestock, but also as sources of fuel (in the forms of firewood, peat or vegetation such as gorse) and a wide range of other resources, as diverse as fish, berries, nuts, sand, clay, gravel, stones, bracken, heather, rushes and reeds (Neeson, 1993, pp158–184; Woodward, 1998; Winchester, 2000, pp123–142).

Surviving commons represent only a fraction of the land subject to common rights in England and Wales before the 19th century. Almost all surviving commons are to be classed as ‘manorial waste’, semi-natural land, usually lying on the margins of a community’s landed resource, but common land in the early modern period also included the open arable fields and meadows, productive farmland held in unenclosed strips in private ownership but subject to common grazing rights after the crop had been taken or when lying fallow. A long process of land reform, culminating in a great surge of enclosure by acts of parliament in the century between circa 1760 and circa 1860, swept away almost all of the open fields and much of the manorial waste, extinguishing common rights over 2.75 million hectares of land – 21 per cent of the total land area of England – and reducing the surviving extent of common land in England and Wales to circa 554,000ha (Turner, 1980, pp178–181; Aitchison, 1990, p273).

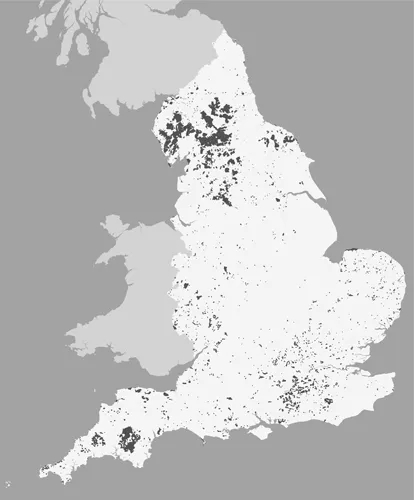

Most of the common land which survived the tide of privatization and enclosure may thus be thought of as ‘leftover’ land, incapable of conversion to intensive agricultural use. The distribution of surviving common land (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2) shows a strong geographical pattern and falls into a number of distinctive types of terrain. Most extensive are upland environments in the hills and mountains of northern England and Wales and the moorlands of south-west England, where, in terms of acreage, the bulk of common land lies. Wetlands, including both peat fen and coastal marsh, form a second distinctive environment in lowland England. Others include the mixed woodland and heath of former royal hunting grounds, such as the Forest of Dean (Gloucestershire), the New Forest (Hampshire) and Ashdown Forest (Sussex), and the small settlement-edge ‘greens’ scattered across East Anglia. Most surviving commons may thus be conceived of as the last fragments of ‘wilderness’ – wild or untamed land on the margins of settlement, lying beyond the cultivated land and dwelt-in spaces. But human use, especially the grazing of livestock, is central to determining their character. Within the spectrum of British commons, two opposite trajectories of ecological and land-use change have dominated recent history. Most upland commons remain an important resource in pastoral farming economies and experienced increasingly heavy grazing pressures across the 20th century, often leading to environmental degradation through overgrazing. In contrast, grazing has ceased on many lowland commons since circa 1950, and traditional harvesting of vegetation for fuel and other purposes has petered out, leading to reversion to scrub land and the loss of the open heathland character (Gadsden, 1988, p1.17; Aitchison and Gadsden, 1992, pp166–167).

Figure 1.1 Registered common land in England

Note: The map excludes commons in the New Forest and Epping Forest (which were exempt from registration) and the Forest of Dean, to which the Commons Registration Act 1965 did not apply.

Source: © Natural England (2010). Material is reproduced with the permission of Natural England, http://www.naturalengland.org.uk

Figure 1.2 Registered common land in Wales

Source: © Countryside Council for Wales (2010). Reproduced with the permission of the Countryside Council for Wales2

The theme of this book is the ‘contested’ nature of common land. It examines the interplay between law, land management and wider cultural conceptions of common land across time, and in so doing seeks to provide an interdisciplinary study of the iconic and often controversial landscapes of the commons. The common land of England and Wales has long been an important resource with multiple and often conflicting land uses. As an important agricultural and recreational resource encompassing some of our most ecologically sensitive environments, it has been the site of profound legal and cultural changes over several centuries. The following chapters aim to address the evolution of common land governance since 1600, providing chronological context at a critical moment in its history. The challenges of re-establishing sustainable management of the commons are to be addressed in the next ten years and beyond when the Commons Act 2006 has been fully implemented. The 2006 Act has introduced reforms to the property rights regime for common land and to the management structures applied to common resource governance, that will significantly strengthen sustainable environmental management and provide a more equitable basis for future access to the land resource. The book offers an assessment of the impact of the 2006 Act, and places the sustainable management of the common lands of England and Wales within the wider international debate concerning the environmental governance of common pool resources, including the work of Elinor Ostrom and other institutional scholars (Ostrom, 1990).

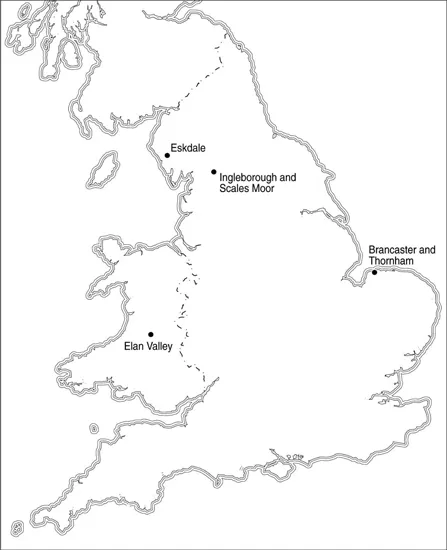

This study takes an interdisciplinary approach, linking historical research in archive sources with qualitative research on modern commons governance undertaken with contemporary stakeholders. It employs case studies in four unique landscapes in England and Wales to illustrate changing patterns of land use, and the differing management principles and regulatory mechanisms applied to common land from circa 1600 to the modern day (see Figure 1.3). Three cover upland commons, in the Lake District of Cumbria, the Pennines of North Yorkshire and the hills of Mid-Wales; the fourth, which includes coastal marshes and a lowland heath in Norfolk, has been chosen to represent surviving common land in lowland England (see Chapters 6 to 9). The case studies inform the book’s broader examination of shifting notions of ‘sustainability’ and of the environmental governance of common land.

The legal framework: Common property rights

Unlike many traditional commons in continental Europe, common land in England and Wales is neither communally owned nor ‘no man’s land’ (terra nullius); rather, it is privately owned land over which others possess use rights, giving them legally recognized access to particular resources. Its use was underpinned from the 13th century until the Commons Registration Act 1965 by a firm and stable framework of property rights, which vested ownership of ‘waste’ in the hands of the lord of the manor, while recognizing the use rights of the local community. The legal framework can be traced back to the statutes of Merton (1235) and Westminster II (1285), which confirmed the lord of the manor’s rights in the soil of the manorial waste (described by Merton as the ‘residue’ of the manor), but also required lords to respect the use rights of free tenants within the manor.3 Lords could approve the waste (i.e. enclose sections of it and rent them out for agricultural use), but the statutes restricted their freedom by recognizing the legal validity of the use rights of commoners. As owners of the soil, lords generally retained a wide range of property rights, including mineral and game rights, and a right to any residual grazing over and above the use rights of commoners.

Figure 1.3 Location of case studies discussed in this book

Source: Authors

English law developed a sophisticated classification of commoners’ use rights, describing both the basis of the right and its nature and purpose. Most rights were ‘appurtenant’ – that is, attached to a landholding (the ‘dominant tenement’) as a subsidiary right. It was also possible, however, for an individual to hold common use rights independently of a holding of land. These are known as common rights ‘in gross’ – ‘a separate inheritance, entirely distinct from any landed property, [which] may be vested in one who has not a foot of ground in the manor’ (Blackstone, 1792, ii, §34). It has been accepted since the mid 19th century that rights in gross are freely alienable and can be transferred by the rights holder to anyone (see Gadsden, 1988, §3.43). In legal terms it is therefore an anomalous category of right – a right over land that is, in itself, a personal right of the holder and (unlike a right appurtenant) not attached to land that it is intended to benefit. Where they do subsist, however, rights in gross cause problems for the sustainable management of common land, as we shall see in subsequent chapters.

The law also recognized the customary use of common land by people from neighbouring settlements (known as common pur cause de vicinage). In legal terms this was a permissive right that applied where two or more contiguous commons usually intercommoned with each other. It was a customary right, and so was implicit in any individual common right (whether appurtenant or in gross) held over either common. The right did not give the holder the right to place his livestock on a contiguous common: rather, it recognized that animals may stray, and protected the common rights holder from an action for trespass where his stock strayed onto the waste of a neighbouring manor. The right could be unilaterally extinguished at any time by the landowner enclosing the common, for example, by fencing it to prevent the straying of stock from one common to another.

The common law recognized six categories of common right (see, generally, Gadsden, 1988, §3.28–3.85; Sydenham 2006, §3.2.1–3.2.7). These are not exclusive categories, however, and in principle any product of the soil, any natural product or wild animal could be the subject matter of a right of common. Many rights that are encountered in practice (including a number discussed in the case studies of commons governance in this book) are difficult to place within one or more of the established categories.

Of the six legal categories of use rights, by far the most significant was common of pasture: the right to graze livestock on the common. This right was, and remains today, centrally important to the rural economy in upland areas of England and Wales. The management of the collective grazing over large agricultural commons was, prior to the Commons Registration Act 1965, organized around one of two principles in most areas – by the application of the principle of levancy and couchancy, or by the imposition of ‘stints’ as a measurement of permitted grazing. The rule of levancy and couchancy determined the number of grazing livestock allowed on the common by reference to the capacity of the land to which the rights attached to feed stock over the winter months. This was not expressed in a numerical form. Stints, on the other hand, permitted a fixed number of livestock to graze the common resource. These mechanisms, and their function in relation to notions of ‘sustainable’ governance, are considered in more detail in Chapters 3 and 4.

The two other common rights most commonly encountered are common of turbary and common of estovers. Common of turbary gave the right to take peat or turf for fuel, and, in principle, must always be attached (appurtenant) to a building or house. The right is limited to taking what is necessary for heating the dominant tenement, and cannot be divided or apportioned between parts of the latter (e.g. if it is divided and sold in separate lots). Common of estovers is similar and gave the right to take wood or other vegetation for necessary purposes. It fell into three sub-categories. ‘House bote’ was the right to take timber for repairing houses or as fuel; ‘plough bote’ to take timber for making or repairing agricultural implements; and ‘hay bote’ was the right to take timber, shrubs or brush to make or repair hedges and fences. The right also extends to taking animal bedding (e.g. bracken or rushes), gorse, heather and reeds. In order to be valid, a claim to estovers must be limited by reference to what is necessary for the maintenance of the dominant tenement to which it is attached, and which it is intended to benefit, or be limited in quantity. It is generally accepted that a right of estovers (and, by implication, the similar right to turbary) cannot be severed from the land it benefits, even if the right is quantified (e.g. if the right gives a right to take two carts of peat per annum from the common) (see Gadsden, 1988, §3.67; Sydenham, 2006, §3.2.4). There is no right to sell estovers or put them to another use other than those recognized by the law.

Other rights of common, less frequently encountered in practice today, are the right of pannage – the right to graze pigs in woodland or forests – and rights to take fish, wild animals and the soil itself. Brief descriptions of the latter categories will be offered here, as both are encountered in the case studies presented in this work, notably in Norfolk (see Chapter 9). Common of piscary is the right to take fish from a lake, river or stream belonging to another. Any land covered with water may be registered as common land, provided it is not foreshore vested in the Crown. The right will normally be registered as appurtenant to a house or land, and in this case it will be limited to what is necessary for the needs of the household it is intended to benefit. There is no reason, in principle, why a right of piscary should not subsist in gross, however, and (somewhat unusually) this is the case with the rights in the Norfolk case study. Rights to take minerals or constituent parts of the soil itself are recognized as profits à prendre in law and can also be the subject matter of a right of common. Most rights to take soil will be appurtenant to land and subject to the restrictions mentioned above in reference to turbary and estovers; but they may also be rights in gross, as in our Norfolk case study. A seventh category is the right to take wild animals (ferae naturae) from the land of another. This can subsist as a profit a prendre in English Law, and can therefore exist as a right of common (Gadsden, 1988, §3.86). It may be difficult to distinguish this category of common right in many cases from instances where a licence or contractual right to take wild animals has been given, such as is given by a right to shoot, hunt or wildfowl over another’s land.

Contested common land

Common land thus has a special legal identity and is also a local material resource. But in cultural terms it has much greater significance than this. As Kenneth Olwig has put it, a common is ‘not simply an institution, but also a symbol of the ideals and values necessary to the maintenance of such institutions’ (Olwig, 2003, p18). An underlying theme of this book is the impact of changing cultural values and perceptions of common land upon the way in which it has been managed across the centuries: the common as a site of multiple, contested ideals and interests. The very existence of common land represents an unfinished contest between ideals of cultivation and wilderness. The lands above or beyond the cultivation line have been variously seen as terrifying, sublime, picturesque or romantic, the subject of legends, literature and art (Thomas, 1983). Without cultivation, vestiges of past human activity often survived on common land where they would otherwise have been destroyed, making the common waste a place where the present confronted the past. Notions of its uncultivated state and marginality might be transferred to the people living among and using the waste: these people might also therefore be defined as somehow wild and uncivilized, picturesque or romantic – the ‘outside’ lands and peoples being assigned the same characteristics, reinforcing their sense of otherness (Thomas, 1983; Pollard, 1997).

To the medieval mind such landscapes were liminal places, where humanity might encounter the supernatural. The otherness of the wilderness can be seen in early medieval Scandinavian cosmology, where the utgård (the sam...