![]() Special Issue Articles

Special Issue Articles![]()

Why Political Scientists Don’t Study Black Women, But Historians and Sociologists Do: On Intersectionality and the Remapping of the Study of Black Political Women

Nikol Alexander-Floyd

Rutgers University, New Brunswick

Recent discussions on intersectionality in political science have sparked increased attention in research to race, gender, and other identity categories, particularly in terms of “descriptive” statistical analysis (Jordan-Zachery 2007). Given that Black women and other women of color developed intersectionality as a means of assessing and confronting their own life circumstances, it behooves us to consider the extent to which political scientists investigate the lives of Black women and issues of race, class, and gender more broadly. More specifically, what do we know about the comparative progress of scholarship on Black women and Black gender politics in the academic field of political science as compared to other disciplines? What are some of the disciplinary challenges that beset the would-be Black feminist political scientist? How do the limits of research on Black political women point to deeper problems regarding political and epistemological orientations of political science?1 In this essay, I offer not a comprehensive multidisciplinary analysis, but a broad snapshot of four sister disciplines: political science, sociology, history, and economics. I provide a general landscape of the research on Black women in these fields both to underscore the relative dearth of literature on Black women in political science, and to set the stage for a conversation about how best to influence the social production of political science as a disciplinary and intellectual “space” as well as the “place” of Black women within it.

An emphasis on space and place in this essay helps me to better conceptualize the politics at work in the knowledge production of the discipline, and I offer, here, a few clarifying definitions. “Space,” as we know, “is regarded largely as a dimension within which matter is located or a grid within which substantive items are contained” (Agnew 2011, 316). However, following McKittrick (2006), I see both space, the general physical and metaphorical context, and place, the specific meanings and patterns of embodiment or social, political, or other forms of relating within a given location or context, as socially produced and contested. Indeed, as Dorthe Possing relates, the “politics of place”: “relates to how places, such as regions, localities, nations, [or disciplines] are used to define groups of people in relation to other groups of people and is about constructing and defining the boundaries of a place, and involves negotiations about who and what is ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ that place” (Possing 2010, 2). I draw attention to the raced and gendered dimensions of political science as an academic space, and the place-making politics necessary to investigate Black political women.2

In addressing these issues of gender, race, space, and place as they relate to Black political women and research, I proceed along two fronts—the first is statistical, assessing the percentages of articles on Black women in political science, specifically as compared to history, sociology, and economics; the second part is interpretive/theoretical, reviewing the possible motivations for the paucity of research and suggesting how it can be counteracted. Significantly, although there are journals, such as Politics & Gender in political science and Gender & Society in sociology, that showcase work on women and gender politics, I focus on mainstream journals in these disciplines, as opposed to those connected to particular subfields, in order to highlight (as I further amplify below) the “absented presence” (Walcott 2001; McKittrick 2006) of Black political women as subjects of research in the space of mainstream political science. This allows us to account for the paradox of Black women’s hypervisibility and centrality to politics, on the one hand, and Black women’s invisibility or “absented presence,” on the other. After surveying mainstream journals within each discipline, I utilize this survey to stage a conversation about the importance of centering Black political women in political science research and the place-making strategies or garreting used to illuminate Black women as subjects of research. Ultimately, I conclude that in order to re-create the intellectual geography of political science, a Perestroika-like effort to restructure the discipline as it relates to expanding research on Black women as political subjects and Black gender politics is required. By Perestroika, I refer to the decade-plus push in mainstream political science to “restructure” or redefine what constitutes knowledge and how to produce knowledge that is politically relevant (Monroe 2005). As it relates to Black political women and Black gender politics, we need to not only increase the amount of research, but also utilize a specifically Black feminist frame of reference (Alexander-Floyd 2007), one that embraces interdisciplinarity and utilizes a broader range of foci and post-positivist methodologies. I now turn to an examination of research on Black women to expose the raced and gendered spatial dimensions of political science relative to other disciplines.

Studying African American Women and Black Gender Politics across Disciplines: Overview and Research Design

Almost thirty years ago, political scientist Ernest Wilson III provoked discussion by highlighting the relative inattention given to studying Black issues in political science relative to other “sister disciplines” (Wilson 1985). Specifically, he asked:

Does the study of Afro-American subjects occupy a different place in our discipline from that of other traditions of inquiry, and if so, why? Why does political science seem to address questions of black political behavior with less assiduity than her sister disciplines address questions of black history or black group behavior? (Wilson 1985, 601)

Wilson addressed these questions arguing that the “paradigmatic” approach of the discipline, its focus on elites and formal politics, mismatched the “empirical” reality of Black politics, which focused on “bottom up” politics and both formal and informal politics, such as social movement activity (604). His review of publications on Black issues in major journals between 1970 and 1985 across the disciplines of political science, history, sociology, and economics, showed political science to lag behind history and sociology in terms of publications. Subsequent examination by Wilson and Frasure (2007) revealed a consistent pattern of relative neglect from 1986 to 2003, concerning race and Black politics in political science compared to other disciplines.

For this study, I used the same approach utilized by Wilson and Frasure in terms of journal selection, the database used to survey research (i.e., JSTOR), and the search for key terms relevant to the subspecialty of Black women’s studies. More specifically, I reviewed the same three top journals in each discipline, namely: The American Political Science Review, American Journal of Political Science, and The Journal of Politics in political science; American Journal of Sociology, American Sociological Review, and Social Forces in sociology; The American Historical Review, American Quarterly, and Journal of American History in history; and American Economic Review, Journal of Political Economy, and The Quarterly Journal of Economics in economics. Also, I used the same two time periods from this previous research, 1970–1985 and 1986–2003, and added a third, 2004–2008. The following terms were searched using JSTOR: “Black women,” “African-American women,” “Afro-American women,” “Black feminism,” or “womanism.” Additionally, consistent with earlier work (Wilson 1985; Wilson and Frasure 2007), I examined totals for full-length articles for each period along three different axes—text only, title only, and abstract only. Each of the latter designations—text, title, and abstract only, yield related, but more or less detailed, levels of results. The full-length articles, as well as titles and abstracts, were determined using a search function in JSTOR, which allows terms to be searched throughout specific journals within particular time frames. In this way, the terms could be isolated across the three dimensions of inquiry (i.e., full-length articles, titles, and abstracts). Given the search terms’ explicit focus on Black women, this study excludes those articles utilizing research on Black women, but framed under the rubric of “women of color.” This approach promises to render those articles directly relevant to the area of study in question.

Some might suggest that the outcomes of this query will yield decidedly predictable results. After all, the relative inattention of political science compared to sociology and history is an anticipated outcome, given prior research on the study of race in political science compared to other fields. This study is important, however, because it provides one means of documenting—and throwing into sharp relief—the current treatment of Black women as subjects of research in mainstream journals across key traditional social science disciplines. My purpose is to let the journals serve as markers of current conditions, telling the story of political science’s suppression of work on Black political women in its own valued idiom of quantitative metrics. The paucity of research on Black women in political science, moreover, can be usefully explained by joining political science’s analysis of the circulation of power with geography’s concerns with the politics of space and place. This conjoining can enable us to see how dominant norms construct intellectual and material space as well as one’s sense of place within disciplines. Following geography scholars, such as Walcott (2001) and McKittrick (2006), I draw on the notion of an “absented presence” to explain the politics at work in the production of space in political science. For McKittrick and Walcott, Black women and Black communities, respectively, are actively elided in the production of narratives of nation, home, and belonging. Likewise, the data I assess highlight the absented presence of Black political subjects in political science research.

Findings: General Numeric and Statistical Profile

The results of this examination paint a very sobering picture regarding the state of research on Black women, particularly in political science. The data discussed below similarly bespeak the absented presence of Black women. Although Black women and Black gender politics are central to US political development, mainstream scholarship “disappears” (Alexander-Floyd 2012) them from the production of political science as an intellectual or disciplinary space.

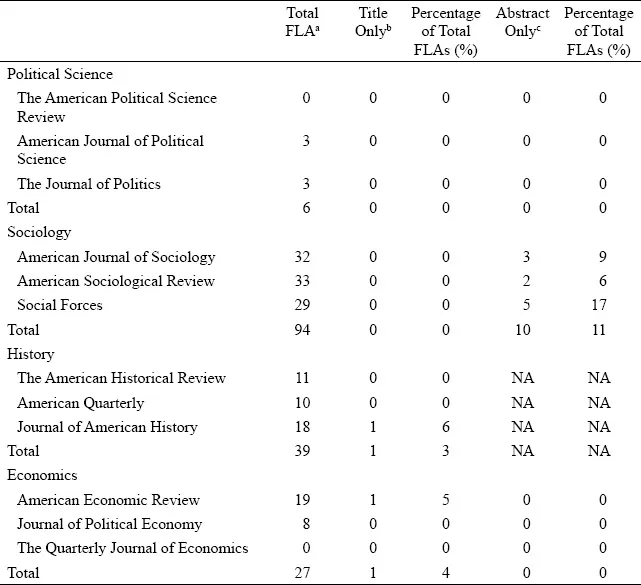

The first-time period, 1970–1985, yielded only three, ninety-four, thirty-nine, and twenty-seven full-length articles with some mention of Black women, African-American women, Afro-American women, Black feminism, or womanism in political science, sociology, history, and economics, respectively (Table 1). Although sociology, history, and economics arguably produced more articles with the key terms related to Black women, they too marginalized the study of Black women in mainstream journals. From 1970 to 1985, the same political science journals published no articles with titles and abstracts indicating a relationship to Black women (Table 1).

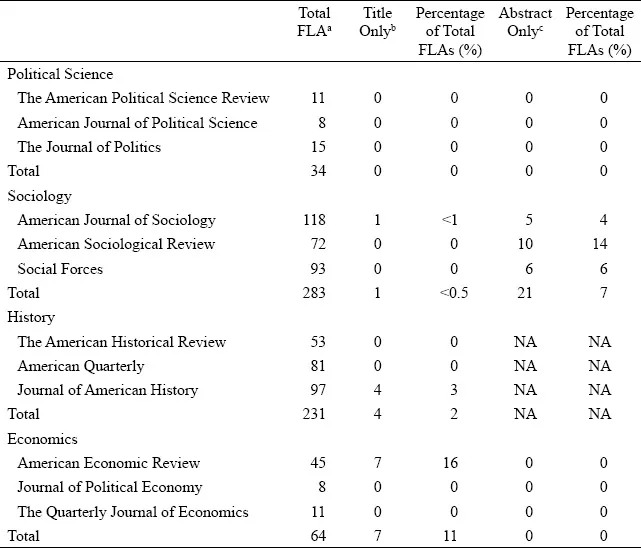

In the second-time period reviewed, 1986–2003, all four disciplines showed progress, but political science still lagged behind sociology and history, continuing to reflect the absented presence of Black women as political subjects. Indeed, as Table 2 indicates, sociology and history were the two top performers in terms of full-length articles with some mention of research terms, with 283 and 234 full-length articles, respectively. A closer look at the results connected to title and abstract only searches, however, reveals a less optimistic picture all around. Between 1986 and 2003, for instance, political science published thirty-two full-length articles with some mention of the terms “black women,” “African-American women,” “Afro-American women,” “Negro women,” “Black feminism,” or “womanism.” None of the journals, however, showed titles or abstracts related to these terms. Also, although sociology had 283 full-length articles, it had only one article with the key search items, and twenty-one abstracts that contained these terms, suggesting a greater prominence of issues related to Black women in this field, compared to political science, but still a relatively small number.

A review of articles with the respective terms, published from 2004 to 2008 reveals little change in the general number and distribution of articles by discipline. Sociology continued to have the largest number of search terms with seventy-three full-length articles including at least one of the primary search terms, with history following at a close second at seventy-one, and political science and economics tied at thirteen articles a piece. None of the journals during the period had any of the key terms (“Black women,” “African-American women,” “Afro-American women,” “negro women,” “black feminism,” or “womanism”) as part of their titles. In terms of abstracts with key terms, sociology generated eight and political science generated two (Table 3).

The absented presence of Black women as political subjects reveals the inherently raced and gendered dimensions of political science as intellectual space. It undergirds a dominant politics of place which suggests that political science as a discipline is inhabited by and/or is the proper “place” of White male political subjects. Oppositional political geographies by subaltern subjects, however, have pushed back against this dominant geographic political configuration. As previously mentioned, in each of the disciplines examined, specialized journals, which address race and/or gender, arguably provide greater exposure to work on Black women as subjects. Political science, for instance, has seen the emergence of the Journal of Politics, Groups, and Identities, and the journal in which this article, “Why Political Scientists Don’t Study Black Women, But Historians and Sociologists Do,” appears, namely, The National Political Science Review, that generally deals with United States and international racial politics, and Journal of Women, Politics, and Policy (formerly Women and Politics) and the newer Politics & Gender, which centers women’s political experiences and gender politics. Sociology’s Gender & Society and Race, Class, and Gender, History’s Journal of Women’s History, and Economics’ Feminist Economics have served as similar outlets. However, even within these venues, conventional wisdom suggests that even greater attention needs to be accorded Black women and Black gender politics. The data here are offered to provide a view of mainstream journals in these disciplines.

Table 1.

Totals for Full-Length Articles (FLAs) by Titles and Abstracts, 1970–1985

Source: Author’s compilation of JSTOR computer-generated citations by discipline, with percentages rounded to whole numbers.

Table 2.

Totals for Full-Length Articles (FLAs) by Titles and Abstracts, 1986–2003