![]()

PART ONE

Evidence from practitioners

![]()

03

ACQUIRE: Evidence from practitioners

What can be asserted without evidence, can be dismissed without evidence

CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS

In organizations, evidence from practitioners is an important source of information. In fact, it may well be the most-used source of information in decision-making processes. In many organizations leadership teams ask employees for their input, managers for their opinion, consultants for their experience, and managers often base their decision on this type of evidence. The quality of decisions will significantly improve when you consider all sources of evidence, including professional expertise, as it can connect external evidence such as scientific research findings to the specific organizational context.

There are many ways in which you can acquire evidence from practitioners. Numerous books and websites are available that can inform you about how to gather evidence in a valid and reliable way, covering important aspects such as sampling procedures, research designs and questionnaire development. This chapter therefore does not aim to give a comprehensive and detailed overview of all methods in which you can acquire evidence from practitioners, but rather a quick summary of key aspects that you should take into account.

3.1 What to ask?

Acquiring evidence from practitioners is not a fishing expedition – it starts with an assumed problem, a preferred solution or a deemed opportunity. Before reaching out to practitioners to ask about their take on the matter it is therefore important that you first clearly describe the (assumed) problem that needs to be solved or the opportunity that needs to be addressed. As discussed in Chapter 2, a good definition of the problem entails at least four elements:

- The problem itself, stated clearly and concisely (What? Who? Where? When?).

- Its (potential) organizational consequences.

- Its assumed major cause(s).

- The PICOC (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Context).

The professional judgement of experienced practitioners inside and outside the organization is an essential component in determining whether the assumed problem is indeed a serious problem and in identifying possible causes. Thus, important questions to ask are:

- Do you agree with the description of the problem?

- Do you see plausible alternative causes of the problem?

- Do you agree that the problem is serious and urgent?

In addition, when you need to make a decision that involves whether to implement a proposed solution, having a clear description of that solution is a prerequisite before you consult practitioners. Again, a good description entails at least four elements:

- The solution itself, stated clearly and concisely (What? Who? Where? When?).

- Its (potential) effect on the problem and underlying cause/s.

- Its costs and benefits.

- The PICOC.

As explained, evidence from practitioners is also an essential component in determining how likely a proposed solution is to work in a particular organizational context. In addition, experienced professionals are often in a good position to rate the preferred solution in terms of implementation costs and other feasibility/risk issues. Finally, experienced professionals may think of alternative solutions that you haven’t considered. Thus, important questions to ask are:

- Do you agree on which solution is the ‘best’ and/or ‘most feasible’?

- Do you see downsides to or unintended negative consequences of the preferred solution?

- Do you see alternative solutions to the problem that may work better?

3.2 Whom to ask?

The first step in gathering evidence from practitioners is determining the target audience. Which practitioners in the organization are, given the question or issue at hand, most likely to provide a valid and reliable judgement? Obviously, we want practitioners whose professional judgement is based on a high level of expertise. Expertise refers to skill and knowledge acquired through training and education coupled with prolonged practice in a specific domain, combined with frequent and direct feedback. So, for example, if the question concerns a proposed solution for high levels of staff absenteeism among lawyers in an international accounting firm, then a practitioner who has only a one-time experience with migrant workers picking fruit should obviously not be the first one to invite to give his/her professional judgement. The quality or trustworthiness of practitioner expertise and judgement depends on the relevance of the practitioner’s training, education and experience, which we discuss in Chapter 4.

3.3 How many practitioners should I ask?

Sample size

In most cases, it is impossible to ask all practitioners in the organization to give their judgement, so we need a sample – a selection of practitioners chosen in such a way that they represent the total population. But, how many practitioners should your sample consist of? Should you ask 1 per cent, 5 per cent, 10 per cent or even 50 per cent of the practitioners in the organization? This depends largely on how accurate you want your evidence to be. Most researchers use a sample size calculator to decide on the sample size.1 The required sample size, however, also depends on practical factors such as time, budget and availability. In addition, qualitative methods (for example, focus groups) involve a substantial smaller sample size than quantitative methods (for example, surveys) because for these methods representativeness is often more important than accuracy.

Selection bias

Another major concern is selection bias. Selection bias, also referred to as sampling bias, occurs when your selection of practitioners leads to an outcome that is different from what you would have obtained if you had enrolled the entire target audience.

![]()

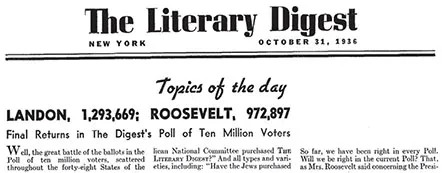

The magazine used a biased sampling plan. They selected the sample using magazine subscriptions, lists of registered car owners and telephone directories. But that sample was not representative of the US public. In the 1930s, Democrats were much less likely to own a car or have a telephone. The sample therefore systematically underrepresented Democrats, and the result was a whopping error of 19 per cent, the largest ever in a major public opinion poll.2

You can prevent selection bias by taking a random sample of the population. However, to get a truly random sample you should not only consider who to ask, but also when to ask. For example, administering a survey on a Monday morning at 9 am to the first 200 employees to start their working day is not random, certainly not when the survey aims to understand the employees’ satisfaction with the company’s flexible working hours. Employees who start their working day on Monday at 9 am may differ from employees who start their working day at 10 am or even later. In addition, some employees with a part-time contract may have a regular day off on Monday. The survey will therefore most likely yield a sample that is not representative for all employees.

3.4 How to ask?

Walking around and asking

The quickest and easiest way to gather evidence from practitioners is by walking around and asking. Of course, thi...