![]()

1 | ‘Lawn’ a Word That Is Strangling Itself |

You might not think it, but the word ‘lawn’ is rather problematic. It really is. It currently conjures a very particular and somewhat constrained image of an area of thickly textured, soft, verdant grass, uniformly levelled and striped with lines laid by a finely bladed mower. The kind of lawn that ‘KEEP OFF THE GRASS’ signs are especially made for (Figure 1.1).

This is perhaps a little disheartening if you happen to have a typically average British-style garden lawn with its mix of different grasses and varying heights (Figure 1.2), with dandelions, buttercups and other plants that weren’t originally invited (Figure 1.3), and it’s quite an unfortunate image since lawns are and have always been so much more than just the restricted selection of grasses we are familiar with today.

To better understand what the lawn has been and can be, it is worth taking a brief look back in time at its origins and history. It will help clarify a few things.

Let’s start with that problematic word. The word ‘lawn’ itself is regarded as having a number of potential origins from around the fourteenth century; perhaps ‘launde’ in Old French, ‘laund’ in Old English or possibly ‘lawnd’ in Middle English; each of these being used to describe an open and pastured glade especially within woodland [1]. Another suggested source is the name of the French town of Laon, which is pronounced rather like the English word ‘long’ but without the ‘g’. It was renowned for producing types of linen cloth made using carded or combed linen in a simple plain weave that produced particularly fine silky fabrics known as ‘laune lynen’ and commonly referred to as ‘lawn’ [2]. Exactly how a French town’s silky fine fabric may have given up its name to a collection of mixed cut grasses and forbs remains hidden in the murky mists of time and linguistics, or it just might not be relevant at all.

Whatever the origins of the word we currently use today, keeping grasses short for some aesthetic purpose is a practice older than the word we now use for it. There is a niggling suggestion that landscape lawns were in existence in Italy during the era of Imperial Rome, but here we have another problem with words again, since the English translation of the relevant Latin text that is thought to mention a lawn also goes on to make mention of a Roman tennis court [3]. With tennis thought to have its origins in twelfth-century France, it seems unlikely that there were actual tennis courts in ancient Italy, perhaps ‘ball court’ might have been a better translation. It also seems likely that the translator was applying modern words to ancient practices; the Latin word ‘Pratum’ meaning ‘prairie’ or ‘meadow’ being translated into ‘lawn’ to suit the context of a wealthy aristocrat’s villa’s garden. Other translators have used ‘level ground’ instead for the same text, so perhaps there were no actual frequently mown lawns as we now understand them in the ancient roman world either, perhaps ‘grassy ground’ might be a better descriptor if the few period garden frescoes are anything to go by. If there were cultivated lawns, and it’s a notable ‘if’ considering that the Mediterranean-type climate is not usually kind to moisture-loving lawn grasses and the period between 250BC and 400AD is thought to have been unusually warm; they were possibly seasonal features or likely to have been necessarily restricted to areas where an irrigating supply of water was available throughout the year, whichever it might possibly have been they weren’t clearly mentioned or shown and apparently didn’t catch on.

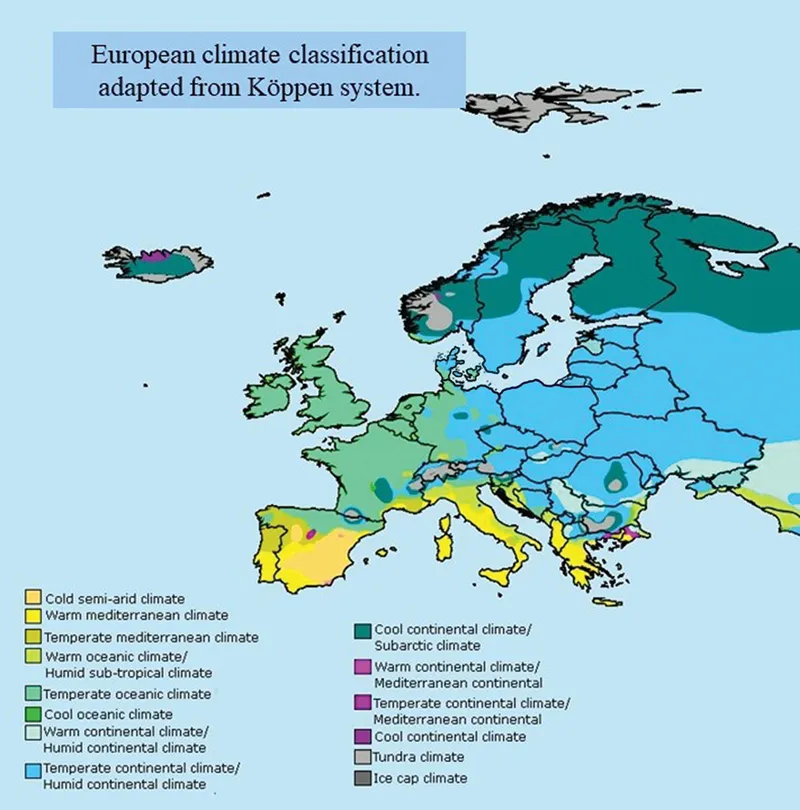

Head farther north and west in Europe to the temperate oceanic climate of northern France and the British Isles (Figure 1.4), and the irrigation of grasses is much less challenging due to the relatively mild temperatures and substantial amount of moisture carried in from the Atlantic Ocean by weather systems associated with the Gulf Stream ocean current.

FIGURE 1.1 Weed-free, thickly textured, verdant green and showing the stripes of the mower. What many a gardener and groundsman would regard as the ‘ideal’ lawn.

FIGURE 1.2 The more commonly encountered British-style lawn is a mix of different grasses and uninvited weeds.

There are records of English King Henry II’s (1113–1189 AD) palace at Clarendon, Wiltshire, containing gardens which were said to ‘boast a wealth of lawns’ [4], although that word still causes problems, and they too may have been pastured meadows. However, this potentially moves the provenance of purposefully keeping grasses low and recognising it as a specific feature to at least the early twelfth century and very probably earlier, although by what method the grasses were kept short remains unclear; it seems likely that it was grazing animals or possibly scythes collecting hay or perhaps a mixture of both. By whatever method the grass was made or kept short, it does indicate that the resulting lawn was an identifiable landscape feature worthy of a name, and thus lawns of some sort may have been around for at least a millennium.

FIGURE 1.3 Even well-managed lawns rarely keep the sharp-cut look for long. Despite the evidence presented to their eyes, the mental image conjured by the word ‘lawn’ has many people envisioning uninterrupted flat surfaces.

FIGURE 1.4 Köppen–Geiger climate classification zones of Europe. The temperate oceanic climate of NW Europe (shown in light green) fosters the luxuriant growth of certain grasses.

Also, in Britain in 1259 AD during the reign of Henry III, it was recorded that the gardens of the Palace of Westminster were levelled with a roller, turf laid and later mown [5]. This now does sound very familiar and is clearly typical lawn-making behaviour. Additionally, in the same century the creation of what is quite clearly a lawn was summarised by the Swabian nobleman Albert Magnus, Count of Bollstadt, in the chapter ‘On the Planting of Pleasure Gardens’ in his thesis De Vegetabilibus et Plantis (On Vegetables and Plants) [6].

Along with a use as a feature in pleasure gardens there are also sports being recorded as being played on grass lawns, with Southampton Old Bowling Green recorded as hosting continuous lawn bowl games since 1299 AD, and as any enthusiast will tell you, lawn bowls requires a very well managed type of lawn indeed, not just any old grass will do; it must provide a fine and even surface on which to play. We may infer that even early on in its history there were different types of lawns, with different uses that were composed of different types of grasses accordingly.

The plant constituents of these early grass lawns are not clearly recorded, but when they are referred to it is apparent that grass lawns were considered quite distinct from the other types of lawns that also existed at the time. Other lawns? Indeed, yes, there were other lawns.

OTHER LAWNS

The informed or curious gardener may have heard of and possibly even seen or touched and inhaled the fragrance of a chamomile lawn (Figure 1.5), and maybe if in the habit of visiting ancient castle gardens or seed company premises may have even encountered the much rarer and just as fragrant thyme lawn. Occasionally even entirely natural thyme lawns may be encountered (Figures 1.6 and 1.7).

FIGURE 1.5 A chamomile lawn (Chamaemelum nobile). As with most lawns, coverage can be variable, and unwanted plants such as grasses, daisies and clovers can appear. The keepers of this lawn report they spend ‘a lot of time weeding it’. In much larger and frequently used chamomile lawns such as that at Buckingham Palace the chamomile is mixed with lawn grasses and is not managed as a pure species lawn at all.

FIGURE 1.6 A natural thyme lawn in flower in the dunes, St. Anne’s-on-Sea, Lancashire. With the day-flying slender scotch burnet moth (Zygaena loti) taking nectar from the flowers. Natural thyme lawns tend to be small and include a mix of other hardy wild plants.

FIGURE 1.7 A natural dune mixed-species lawn on almost pure mineral sand with the forbs Thymus praecox (mother of thyme), Centaurium erythraea (common centaury), Lotus corniculatus (bird’s foot trefoil) and Hypochaeris radicata (cat’s ear) amid the sparse grasses and dry moss.

These fragrant and floral lawns have a pedigree as old as grass lawns, but the key features here are not specifically a green sward or a playable surface, but rather distinctly the focus is on scented leaves and seasonal flowers. Both Chamaemelum nobile (noble or Roman chamomile) and Thymus praecox (mother of thyme) are strongly aromatic, most especially when the leaves are bruised or crushed underfoot.

It is the kind of fragrance that a bit of treading can release rather well. ‘Treading the lawn’ was a practice well-understood in a time when using strewing herbs such as chamomile, mint, lavender, pennyroyal, meadow sweet and marjoram on floors of houses was undertaken in all the very best households (King Charles II appointed his own royal herb strewer). The venerable playwright William Shakespeare even makes mention of the custom known as ‘treading the chamomile’ in King Henry IV, Part 1 ‘Though the chamomile, the more it is trodden upon, the faster it grows’ (Figure 1.8).

FIGURE 1.8 The edge of a chamomile lawn. Indicative of how mowing and treading can influence plant growth and behaviour. Where the mower has not reached and the lawn is untrodden the growth is upwards towards flowering rather than outwards and ground-covering. The non-flowering and creeping cultivar clone ‘Treneague’ can be used to overcome this, especially if trodden on from time to time.

Treading, walking, laying and even dancing on plants of all sorts doesn’t seem to have particularly bothered our medieval forebears, possibly because of all that strewing going on. Tapestries and paintings of the period from across Europe show the noble and wealthy classes taking their ease in enclosed gardens, both on and within grassed areas embellished with flowering and scented plants of all sorts (Figure 1.9). It is not just the daisies that are shown in some medieval lawns but ...