![]()

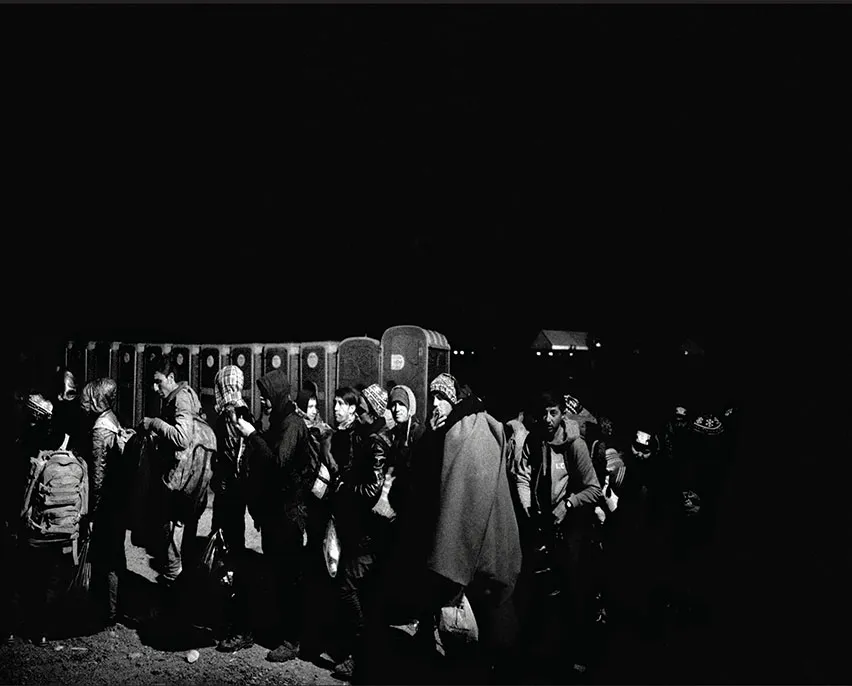

◀ A few kilometres outside Macedonia, a queue has formed. They are all waiting for the first welded-mesh and barbed-wire gate to be opened, the first stage of entry into the “corridor” located on what is known as the Balkan route. The only way to get through is as the holder of an identity card or a document issued by the Greek authorities establishing the bearer’s nationality. In some cases, procurement of false documents will allow the bearer to pass for a Syrian, an Iraqi or an Afghan and to continue on their journey. Olivier Sarrazin, Idomeni, Greece, December 2015.

Chapter 1

Visualising Migration

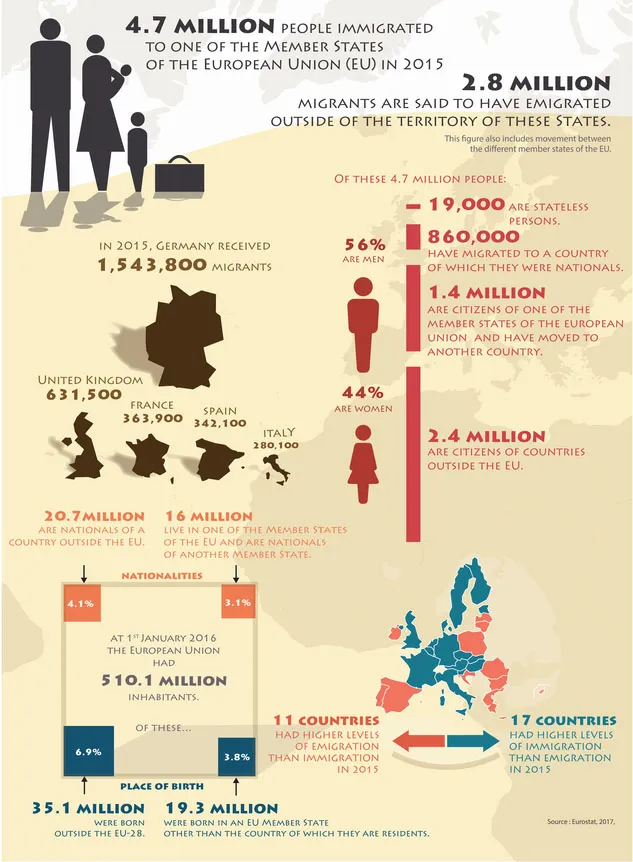

International migration has long been a subject of research and analysis in several disciplines of the social sciences, using a variety of methods and from a range of perspectives. Yet, despite this diversity in approaches, some conclusions are shared by the entire scientific community: no demographer, geographer, sociologist or political scientist – regardless of their political leanings – would claim that Europe is currently “inundated” with “waves” of new arrivals or would defend the idea that erecting more “barriers to entry” and “walls” would somehow make it possible to “regulate migrant flows”. Nevertheless, these beliefs underpin public discourse and policy at the EU and state level. Immigration, like climate change, is one of the challenges facing the world where “alternative facts” mask even the most well-established truths. Our aim here is to reinstate some of these facts and to deconstruct some simplistic misconceptions.

Probing the History of Migration

The expression “Fortress Europe” was initially popularised by advocates of freedom of movement in the late 1990s. The phrase marked a new chapter in migration policy, namely that it was increasingly becoming impossible to legally and safely enter the Schengen area, a geographic entity founded on the premise that those regions posing a so-called “migration risk” ought to be excluded. The European Union (EU) was indeed entering a new era of control over borders and over people’s rights to travel and settle.

From the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1815) through to the First World War (1914–1918), the main areas of Western Europe together formed a space that was relatively open to cross-border travel, notably because right up until the 1880s the idea of identity defined as belonging to a particular nation-state was far from hegemonic and conferred relatively few rights or special protections. The main issue at the time was emigration and, more specifically, across the ocean (see p. 5). However, the right to movement did not apply to all in the same way and was already a constituent part of citizenship regimes so that even within national territories workers were tied to their employers and risked falling foul of vagrancy laws when they broke free of them without authorisation.

After the First World War, it became more difficult to cross national borders, which had been redrawn following the disappearance of four empires (the German, Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires). Thus began the reign of passports and travel permits, with which Jews and other populations fleeing persecution in Germany were confronted in the late 1930s. The first few decades of the “age of extremes ” (from the 1910s to the 1950s), however, were also an “age of movement”, with the two world wars, genocidal projects and the provisions of peace treaties leading to mass movements of population. Tens of millions of men and women fled their home regions or were deported. The reception of refugees and “demographic engineering” – which sought to streamline or purify national groups – were, at that time, closely connected.

From the 1950s to the 1990s, policies of economic growth and the Cold War ushered in Europe’s “age of immigration”. But it was not until the very end of this period that countries in southern Europe started experiencing positive rates of net migration. In general, the question of refugees became secondary. Most importantly, migration was an answer to political considerations as part of the confrontation with the Eastern Bloc. Labour agreements (with European countries such as Yugoslavia and Portugal, amongst others, or countries outside Europe, such as Morocco, Turkey, etc.), combined with regularisation of the status of those people arriving by their own means, made it possible to meet the demand for unskilled labour. During this period, gradual decolonisation slowly reduced possibilities for travel between imperial metropoles and their former possessions. In the middle of the 1980s, the main countries of the EU extended their restrictions making visas mandatory for all nationals from developing countries.

The fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet regime caused thousands of kilometres of new borderlines to spring up. This upheaval led to movements of people, in particular linked to the wars in the former Yugoslavia. The EU, henceforth in charge of controlling its external borders, set about continuously fortifying the separation with the “Global South”. Directives and measures – Schengen visas, movement tracking, controls in the countries of departure, etc. – followed in quick succession to protect Europe from migrants, which key member states were trying to keep away from their borders. With the exception of the brief reprieve opened by Germany at the end of the summer of 2015, Europe’s response to the mass displacement of people triggered by the recent wars in Syria offers a ruthlessly hyperbolic demonstration of the effects of these policies.

EMMANUEL BLANCHARD

Yesterday’s migrants . . . and today’s

When Europe was a Land of Emigration

For many pundits and politicians, the notion that Europe is one of the most attractive destinations for migrants no longer needs to be demonstrated. However, actual observation of the demographics of the whole continent reveals a more nuanced picture. The majority of migrations have actually occurred within Europe (from Poland to Britain, from Greece or Croatia to Germany, etc.), whereas on a global scale, the primary asylum destinations (Kenya, Pakistan, Turkey, etc.) are, in fact, outside Europe. In addition, the EU is characterised by strong emigration, with only half of the 28 member countries of the EU having a significant positive rate of net migration. France, for example, has a positive figure for net migration, but from the mid-2000s onwards between 150,000 and 200,000 people born in France have moved away from the country every year. This is a relatively new nationwide phenomenon for a country that has not traditionally been a country of emigration. These departures, furthermore, find no parallels in the great waves of migration that Europe has known in the past.

From the beginning of the nineteenth century until the 1950s, the principal states that currently make up the EU (Germany, Great Britain and Ireland, Poland, Italy, Spain, etc.), with the exception of France, were all countries of net emigration, and it was only much later that they became countries of immigration. Between 1840 and 1920, nearly 50 million people left the European continent for good and went to settle in the “New Worlds” of North America (United States and Canada), South America (Brazil, Argentina) and Oceania (Australia and New Zealand), and also in “settler colonies” as they were known. In general, there were few formal procedures and almost no restrictions. On the contrary, people were in fact encouraged to move there by public authorities. Throughout the nineteenth century, the effective exile of millions of sub-proletarians and landless peasants was seen as a “safety valve” and a step towards resolution of the “social question” and “the extinction of pauperism”.

The measures adopted in the United States at the beginning of the 1920s marked the end of the period where, aside from the formalities of registration and medical checks carried out by the Bureau of Immigration on Ellis Island (the island in New York beside the one that is home to the Statue of Liberty), immigrants arriving from Europe faced few obligations.

From 1882 onwards, however, the Chinese Exclusion Act, banned entry to the United States for Chinese workers of whom there were many in California and along the Pacific coast. This text, with unashamedly racist overtones, was to have a bright future. After several revisions it remained in force until the mid-1960s and served as inspiration for a number of “reformers”. After the First World War, it was held up as a model by “experts” (jurists, economists, doctors, etc.) in France and Britain, who called for the establishment of a selective immigration policy and for the exclusion of “undesirables”.

Thus, having benefited thoroughly from a regime of open borders during its industrial leap forward, Europe gradually shifted towards the establishment of restrictive immigration regimes. From the end of the 1920s, the ability to travel and immigrate was increasingly attached to economic criteria or nationality, only just dissembling a racialised hierarchy of potential immigrants.

EMMANUEL BLANCHARD

Milos Virijevic, Belgrade, Serbia, May 2017

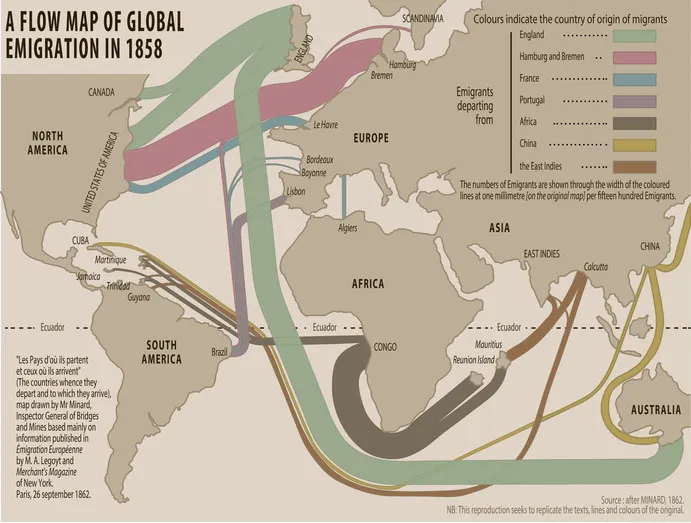

Migration around the world in 1858 This map was drawn in 1862 by Charles Joseph Minard, a French civil engineer widely known for his graphic representations and of flows in particular. On a semantic level, this map reveals global migration movements thanks to two-pronged innovation: first, the representation of flows of people using arrows whose width is proportional to the value being represented and, second, the use of curved lines rather than straight ones. These curvilinear arrows, which recognise alternations between land masses and sea, show the intensity of maritime travel. The graphic semiology is part of a simplified geographical overview (schematised coastlines and removal of borders) and makes use of symbols: the variation in widths to visually represent proportion; the choice of highly evocative colours (pink for emigrants from northern Europe, black for some African emigrants, etc.) implying the direction of travel (emigration).

Probing Categories

The categories applied to migration appear self-evident. When the distinction between a “migrant”, “refugee”, “asylum seeker”, “expatriate” or “failed claimant” is difficult to determine, this is blamed on a lack of information. The specific features of each category are supposed to be clearly distinguishable in so far as they have been explicitly described. However, these taxonomies are in fact porous and highly fluid.

First, this is because the classification of individuals with complex social backgrounds is complicated and therefore always to some extent arbitrary. After all, what is the meaning of putting people into categories if not the separation of what might have been grouped together or merging of what might have been separated? Second, because since the reinforcement of border closure policies in the 1980s, labels and other descriptors have proliferated. Quantification, fencing-in and separation have become high-stakes policy issues that made it possible to exclude and channel certain individuals (but not others). It thus becomes both an intellectual and a political necessity to question the methods used to categorise migrants.

The distinction between legal and illegal – at the heart of what is represented here – seems particularly fragile. Most foreigners who are currently in an “irregular situation” in Europe entered Europe legally. It is the change in migration policy in the host countries and not their own migration that has led to them being regarded as “illegal”. Some research has ...