![]() Part One The Theory

Part One The Theory![]()

1 THEATRE, THE FIRST HUMAN INVENTION

Theatre is the first human invention and also the invention which paves the way for all other inventions and discoveries.

Theatre is born when the human being discovers that it can observe itself; when it discovers that, in this act of seeing, it can see itself – see itself in situ: see itself seeing.

Observing itself, the human being perceives what it is, discovers what it is not and imagines what it could become. It perceives where it is and where it is not, and imagines where it could go. A triad comes into being. The observing-I, the I-in-situ, and the not-I, that is, the other. The human being alone possesses this faculty for self-observation in an imaginary mirror. (Doubtless it will have had prior experience of other mirrors – its mother's eyes, its reflection in water – but henceforward it is able to view itself by means of imagination alone.) The ‘aesthetic space’, which we will treat later, offers this imaginary mirror.

Therein resides the essence of theatre: in the human being observing itself. The human being not only ‘makes’ theatre: it ‘is’ theatre. And some human beings, besides being theatre, also make theatre. We all of us are; some of us also do.

Theatre has nothing to do with buildings or other physical constructions. Theatre – or theatricality – is this capacity, this human property which allows man to observe himself in action, in activity. The self-knowledge thus acquired allows him to be the subject (the one who observes) of another subject (the one who acts). It allows him to imagine variations of his action, to study alternatives. Man can see himself in the act of seeing, in the act of acting, in the act of feeling, the act of thinking. Feel himself feeling, think himself thinking.

The cat chases the rat, the lion pursues its prey, but neither animal is capable of self-observation. When a man hunts a bison, he sees himself in the act of hunting; which is why he can paint a picture of the hunter – himself – hunting the bison. He can invent painting because he has invented theatre: he has seen himself in the act of seeing. An actor, acting, taking action, he has learnt to be his own spectator. This spectator (spect-actor) is not only an object; he is a subject because he can also act on the actor – the spect-actor is the actor, he can guide him, change him. A spect-actor acting on the actor who acts.

Birds sing, but know nothing about music. Singing forms part of their animal activity – along with eating, drinking, coupling – and their song never varies; a nightingale will never try to sing like a swallow, nor a thrush like a lark. But the human being is capable of singing and seeing itself in the act of singing. That is why it can imitate animals, discover variations of its own song, compose. Birds are not composers, they are not even interpreters of music. They sing, just as they eat, drink and couple. Only the human being is tri-dimensional (the I who observes, the I-

in-situ and the not-I) because it alone is capable of dichotomy (seeing itself seeing). And as it places itself inside and outside its situation, actually there, potentially here, it needs to symbolise that distance which separates space and divides time, the distance from ‘I am’ to ‘I can be’, and from present to future; it needs to symbolise this potential, to create symbols which occupy the space of

what is, but does not exist concretely, of what is possible and could one day exist. So it creates symbolic languages: painting, music, words. Animals have access only to a language of signals (signs made up of calls, grunts, grimaces). The alarm call of an African monkey will be understood perfectly by an Amazonian monkey of the same species,

but the word signifying alarm –

danger – spoken in good Portuguese, will never be understood by a Swede or a Norwegian (who will, however, be able to understand the alarm signalled by the face of the person calling).

The being becomes human when it invents theatre.

In the beginning, actor and spectator coexisted in the same person; the point at which they were separated, when some specialised as actors and others as spectators, marks the birth of the theatrical forms we know today. Also born at this time were ‘theatres’, architectural constructions intended to make sacred this division, this specialisation. The profession of ‘actor’ takes its first bow.

The theatrical profession, which belongs to a few, should not hide the existence and permanence of the theatrical vocation, which belongs to all. Theatre is a vocation for all human beings: it is the true nature of humanity.

The Theatre of the Oppressed is a system of physical exercises, aesthetic games, image techniques and special improvisations whose goal is to safeguard, develop and reshape this human vocation, by turning the practice of theatre into an effective tool for the comprehension of social and personal problems and the search for their solutions.

The Theatre of the Oppressed has three main branches – the educational, the social and the therapeutic. This book, which is focused on the therapeutic branch, uses old techniques from the ‘arsenal’

of the Theatre of the Oppressed in new ways, and introduces recent techniques (1988–93) specific to the Cop in the Head. I hope that they will be as useful in the field of therapy as in the domain of theatre. (At the present moment, in Brazil, having recently been elected ‘Vereador’ (city councillor) for Rio de Janeiro, I am trying to develop a new possible application of Theatre of the Oppressed, the ‘Legislative Theatre’. But it is still in its beginnings… .)

The title ‘The Rainbow of Desire’ is inspired by the name of one technique presented here. In fact, all the techniques have something to do with the rainbow of desire: all try to assist the analysis of its colours, with a view to combining them in other desired proportions, configurations and frameworks.

![]()

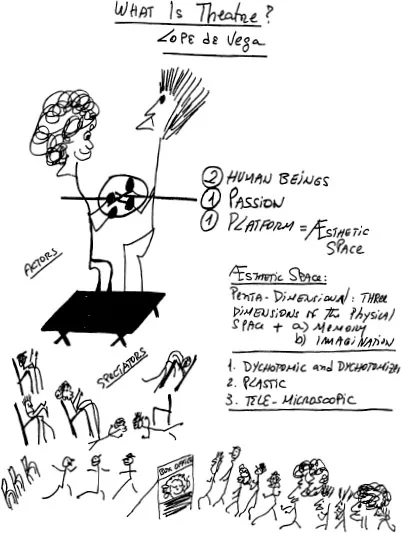

2 HUMAN BEINGS, A PASSION AND A PLATFORM: THE ‘AESTHETIC SPACE’

What is theatre?

Over the centuries theatre has been defined in thousands of ways. Of these definitions, to my mind the simplest and most essential is that provided by Lope de Vega, for whom ‘theatre is two human beings, a passion and a platform’. Theatre is the passionate combat of two human beings on a platform.

Two beings – not just one – because theatre studies the multiple interrelations of men and women living in society, rather than limiting itself to the contemplation of each solitary individual taken in isolation. Theatre denotes conflict, contradiction, confrontation, defiance. And the dramatic action lies in the variation and movement of this equation, of these opposing forces. Monologues will not be ‘theatre’ unless the antagonist, though absent, is implied; unless her absence is present.

The passion is necessary: theatre, as an art, does not have as its object the commonplace and the trivial, the valueless. It attaches itself to actions in which the characters have an investment, situations in which they venture their lives and their feelings, their moral and their political choices: their passions! What is a passion? It is a feeling for someone or something, or an idea, that we prize more highly than our own life.

And where does the platform fit into all this? In his use of the word ‘platform’, Lope de Vega reduces all theatres, all existing forms of theatrical architecture, to their simplest equipment and their most elementary expression: a space set apart, a ‘place of representation’. This can equally well be a few planks in a public square, an Italian rococo stage, an Elizabethan playhouse or a Spanish ‘corral’; today it can be the arena, just as yesterday this was the Greek stage. Modern experiments have transformed lorries, boats, even swimming pools, into theatre stages, and even the stage/audience division has been fragmented in various ways. However, in all cases, separation remains a feature: one space (or more) is intended for the actors and another (or several others) for the spectators, whether these spaces are stationary or mobile.

What is theatre? Boal's expression of Lope de Vega's ‘theatre as “two human beings, a passion and a platform”’. Like any space, these various spaces possess, from a physical point of view, three dimensions: length, width and height – the objective dimensions.

Into this empty space, surrounded by things – this stage – other things can enter, other beings. Like the space itself, the things in this space (and the spaces which these things are, every thing being a space) possess these same three physical, objective and measurable dimensions, which are independent of the individuality of each observer. The same surface can seem big to me and small to someone else, but if we measure it we will always find the same square metreage. The same applies to time: an interval of time can seem long to me and short to another; but the number of minutes will be the same.

Spaces possess, then, subjective dimensions: an affective dimension and an oneiric

dimension, which we will study later.

THE AESTHETIC SPACE

The object which Lope de Vega calls the ‘platform’ has as its primary function the creation of a separation, a division between the space of the actor – the one who acts – and the space of the spectator – the one who observes (spectare = to see).

However, this separation becomes more important

per se than the object which produces it. It can occur even without that object. The separation of spaces can occur without the ‘platform’ existing as an actual object. All that is required is that, within the bounds of a certain space, spectators and actors designate a more restricted space as ‘stage’: an aesthetic

space. Whatever the process by which the bounds of this limited space have been determined, we then accept it as an aesthetic space, and it acquires all of the concomitant properties, even in the absence of a physical platform or any other object; it is a space within a space, a superposition of spaces. It can be a corner of the room, or a space around a tree in the open air. We simply decide that ‘here’ is ‘the stage’ and the rest of the room, or the rest of whatever space is being used, is ‘the auditorium’: a smaller space within a larger space. The interpenetration of these two spaces is the

aesthetic space.

An overlaying of spaces; a space is created subjectively by the gaze of the spectators – witnesses present or imagined – inside a space which already existed physically, in three dimensions. The

latter is contemporaneous with the spectator; the former travels in time.

The aesthetic space thus comes into being because the combined attention of a whole audience converges upon it; it attracts, centripetally, like a black hole. This force of attraction is aided by the very structure of theatres and the positioning of stages, which oblige the spectators all to look in the same direction; and it is abetted by the simple presence of actors and spectators who connive in their acceptance of the theatrical codes and their participation in the celebratio...