![]()

PART I

UNDERSTANDING THE THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The first section of this book prepares the reader to work with the Multiple Ethical Paradigms and Turbulence Theory. It presents, in some detail, the theoretical framework for solving or resolving complex ethical dilemmas.

Chapter 1 provides an overview of the two underlying concepts. It offers a brief description of the ethics of justice, critique, care, and the profession, and then introduces the four categories of light, moderate, extreme, and severe turbulence. It also provides an ethical dilemma and resolves it using both the Multiple Ethical Paradigms and Turbulence Theory. Additionally, the designing of a Turbulence Gauge is highlighted.

In Chapter 2, considerable background to the Multiple Ethical Paradigms is offered. Literature emanating from each of the four ethical perspectives is presented. All of the ethics come from rich intellectual traditions, and this chapter highlights appropriate scholars and their work.

Chapter 3 explores Turbulence Theory and includes the evolution of this concept that now includes positionality, cascading, and stability as well as its application in helping to gauge the impact of disturbances in educational settings. Turbulence Theory is also considered in light of its relationship to previous and contemporary scholarship.

![]()

Chapter 1

Overview of the Book

Case Contributed by Noëlle Jacquelin

The answer to fear is not to cower and hide; It is not to surrender feebly without contest. The answer is to stand and face it boldly, look at it, analyze it, and, in the end, act. (Eleanor Roosevelt, 1963)

In the beginning of the 21st Century, in an era of wars, terrorism, hurricanes, volcanoes, tornados, financial uncertainty, and high-stakes testing, educational leaders are faced with even more daunting decision-making difficulties than in a more tranquil period. Educational leaders now face profound moral decisions regarding their classrooms, schools, school districts, and higher educational institutions in an ever-changing and challenging world. Beyond the normal ethical decisions they must make, they also need to take into account evacuation plans, psychological assistance, conflict resolutions, and global events and threats that impact their communities. The most difficult decisions to solve are ethical ones that require dealing with paradoxes and complexities. This book is designed to assist educational leaders in the ethical decision-making process. It is especially designed to help them during turbulent times.

Even in the best of times, educational leaders have confronted difficult moral dilemmas each day. Foster (1986, p. 33) explained it this way: “Each administrative decision carries with it a restructuring of human life: that is why administration at its heart is the resolution of moral dilemmas.” Fullan (2001) speaks of leaders being asked to constantly provide “once-and-for-all answers” to big problems that are “complex, rife with paradoxes and dilemmas” (p. 2). Homer-Dixon (2000) carries these ideas further when he states:

We demand that (leaders) solve, or at least manage, a multitude of interconnected problems that can develop into crises without warning; we require them to navigate an increasingly turbulent reality that is, in key aspects, literally incomprehensible to the human mind; we buffet them on every side with bolder, more powerful special interests that challenge every innovative policy idea; we submerge them in often unhelpful and distracting information; and we force them to decide and act at an even faster pace. (p. 15)

In this complex and challenging era, more and more is being asked of those in charge. Under these circumstances, no longer can central and school administrators do it all alone (Donaldson, 2001; Fullan, 2001, 2003). For the purposes of this book, educational leadership is defined broadly to encompass not only administrators but also those who take on decision-making functions through distributive leadership (Elmore, 2000; Gronn, 2001; Guiney, 2001; Hart, 1994a, 1994b; Katzenmeyer & Moller, 2001; Neufeld & Roper, 2003; Poglinco, Bach, Hovde, Rosenblum, Saunders, & Supovitz, 2003; Spillane, Halverson, & Diamond, 2001; Spillane &, Orina, 2005). Educational leaders would then include an ever-increasing list of positions and titles, such as teacher leaders, instructional coaches, coordinators, department chairs, and members of crisis management teams. In particular, teacher leaders might serve as heads of charter schools and of learning communities or take on the roles of cooperating teachers and supervisors assisting universities in preparing the next generation of educators (Campbell, 2004; Glickman, 2002; Hansen, 2001; Hostetler, 1997; Strike & Ternasky, 1993).

There is a caveat, however, concerning distributive leadership. In this era of accountability, final decisions are expected to reside with the person who is at the top of the hierarchy. In the United States, public school principals and superintendents, for example, have been singled out in legislation, such as the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB), to make the hard decisions and be held accountable for them. Thus, there is a tension between the appointed leader and those who also should have something to say in the decision-making process. Despite this warning, there will be examples of distributive leadership woven throughout the ethical dilemmas.

In this book, the term ethics relates well to values as discussed by Begley (1999), especially when he turned to decision making and problem solving. Begley emphasized that decision making “inevitably involves values to the extent that preferred alternatives are selected and others are rejected” (p. 4). Begley also stressed the problems that educational leaders face because of value conflicts. Some of these conflicts involve articulated values, while others deal with core values that have not been made known and that “may be incompatible with organizational or community values” (p. 4). Such value conflicts are described throughout this book within the different ethical dilemmas.

At the theoretical level, this book rests on the concepts of the Multiple Ethical Paradigms of the ethics of justice, critique, care, and the profession (Shapiro & Stefkovich, 2001, 2005, 2011), and Turbulence Theory (Gross, 1998, 2004, 2006). These combined ideas form the theoretical framework that is meant to help educational leaders solve dilemmas in an unstable era. It brings together what Goleman (1995) calls the “two minds,” the rational and the emotional. This amalgamation attempts to maintain the balance between two distinctly different ways of knowing. Goleman described them well when he wrote:

These two fundamentally different ways of knowing interact to construct our mental life. One, the rational mind, is the mode of comprehension we are typically conscious of: more prominent in awareness, thoughtful, able to ponder and reflect. But alongside that there is another system of knowing impulsive and powerful, if sometimes illogical—the emotional mind …

The emotional/rational dichotomy approximates the folk distinction between “heart” and “head”; knowing something is right “in your heart” is a different order of conviction—somehow a deeper kind of certainty—than thinking so with your rational mind. (p. 8)

The foci of this book, then, are the following:

1. to present the Multiple Ethical Paradigms of justice, critique, care, and the profession that deals primarily with the rational mind (Chapter 2);

2. to introduce the concept of Turbulence Theory that taps the emotional mind (Chapter 3);

3. to provide authentic ethical dilemmas that will be analyzed using the combination of the Multiple Ethical Paradigms and Turbulence Theory (Chapter 4 through Chapter 10);

4. to assist educational leaders in resolving and sometimes even solving difficult dilemmas in uncertain times.

This particular chapter is meant to provide an overview to the book by offering a brief introduction to the Multiple Ethical Paradigms and to Turbulence Theory. It is followed by an authentic ethical dilemma from the field to serve as an illustration of how to make use of these two theoretical concepts. The case What in God’s Name? is meant to give the reader a taste of the many ethical dilemmas to follow.

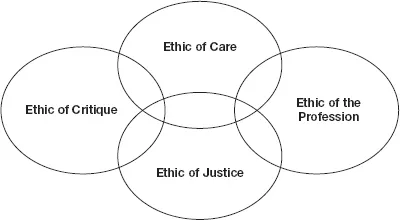

A BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO THE MULTIPLE ETHICAL PARADIGMS

The underlying perspectives for helping educational leaders solve dilemmas in turbulent times are provided in a book entitled Ethical Leadership and Decision Making in Education: Applying Theoretical Perspectives to Complex Dilemmas. This work, written by Shapiro and Stefkovich (2001, 2005, 2011), takes into account the Multiple Ethical Paradigms of justice, critique, care, and the profession. Starratt (1994a) had brought together the three paradigms of justice, critique, and care in his approach to ethics and schools. This model developed those ethics still further and added a fourth lens or paradigm, the ethic of the profession.

Turning to Shapiro and Stefkovich’s Multiple Ethical Paradigms approach for an overview, one of the lenses is the ethic of justice. This model focuses on rights, law, and policies. It is part of a liberal democratic tradition that believes in faith in the legal system and in progress (Delgado, 1995). This paradigm focuses on concepts that include fairness, equality, and individual freedom. This lens leads to questions, such as: Is there a law, right, or policy that would be appropriate for resolving a particular ethical dilemma? Why is this law, right, or policy the correct one for this particular case? How should the law, right, or policy be implemented?

The ethic of critique has been discussed by a number of writers and activists who are not convinced by the analytic and rational approach of the justice paradigm. Some of these scholars find a tension between the ethic of justice—focusing on laws, rights, or policies—and, for example, the concept of democracy. Not only do they force us to rethink important concepts such as democracy but they also ask us to redefine and reframe other concepts such as privilege, power, culture, language, and, in particular, social justice. This ethic asks educators to deal with the difficult questions regarding class, race, gender, and other areas of difference, including: Who makes the laws, rules, or policies? Who benefits from these laws, rules, or policies? Who has the power? And who are the silenced voices?

While the ethic of care has been articulated recently by some male ethicists, for the most part this ethic has been discussed in contemporary times in greater detail by female scholars, who have challenged the dominant—and what they consider to be often patriarchal—ethic of justice in our society by turning to the ethic of care for moral decision making. Attention to this ethic can lead to other discussions of concepts such as loyalty, trust, and empowerment. This ethic asks that individuals consider the consequences of their decisions and actions. It asks them to take into account questions, such as: Who will benefit from what I decide? Who will be hurt by my actions? What are the long-term effects of a decision I make today? And, if I am helped by someone now, what should I do in the future about giving back to this individual or to society in general?

Finally, the ethic of the profession is best illustrated, for educational leaders, in a document developed by the National Policy Board for Educational Administration’s Interstate School Leaders Licensure Consortium (ISLLC) (NPBEA, 1996) and then in a revised document entitled “Educational Leadership Policy Standards: ISLLC 2008,” designed by the National Policy Board for Educational Administration (NPBEA). In the most recent modification, Standard 5 states that “An education leader promotes the success of every student by acting with integrity, fairness, and in an ethical manner” (NPBEA, 2008, pp. 4–5; emphasis added). This ethic places the student at the center of the decision-making process. It also takes into account not only the standards of the profession but the ethics of the community, the personal and professional codes of an educational leader, and the professional codes of a number of educational organizations (Shapiro & Stefkovich, 2001, 2005, 2011). The ethic of the profession in resolving or solving an ethical dilemma raises questions, including: What is in the best interests of the student? What are the personal and professional codes of an educational leader? What professional organizations’ codes of ethics should be considered? What does the community think about this issue? And what is the appropriate way for a professional to act in this particular situation?

What follows is a representation of the Multiple Ethical Paradigms (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 “Multiple Ethical Paradigms”

A BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO TURBULENCE THEORY

In his books Staying Centered: Curriculum Leadership in a Turbulent Era and Promises Kept: Sustaining School and District Leadership in Turbulent Times, Gross (1998, 2004) found that sites that had developed curriculum, instructional, and assessment innovations for several years all experienced some degree of turbulence or volatile conditions. Further, he discovered that the degree of turbulence at the 10 schools and districts he had studied could be divided into four levels:

• Light turbulence includes ongoing issues with the normal functioning of the school. Examples of this include dealing with a disjointed community or geographic isolation of the institution. One school in Gross’ study, for instance, responded to its geographic isolation by joining a national reform organization and by hosting an annual statewide conference on innovation at small schools. The key to light turbulence is the fact that it is part of the institution’s environment and that it can be handled easily in a way that will, at least, keep the issue in check.

• Moderate turbulence is related to specific issues that are widely recognized as important and needing to be solved. The loss of an important support structure would be one example of moderate turbulence. Rapid growth of the student body would be another example of moderate turbulence. Faced with the sudden expansion in students, a school that Gross investigated made this issue the center of in-service meetings just prior to the opening of school. Faculty members were trained in ways to welcome, listen to, and integrate new students. The principal modeled the attitude of acceptance by stating that the new students were not simply joining their institution but had every right to help change the school, since that fit their school’s philosophy. Moderate turbulence, therefore, is not part of normal operations; it quickly gains nearly everyone’s attention and yet it can be responded to with a focused effort.

• Severe turbulence is found in cases where the whole enterprise seems threatened. A conflict of community values was at the heart of one instance of severe turbulence in Gross’ work. In that case, members of the community were deeply divided in their reaction to specific reforms. School board elections became highly emotional, friendships were ended due to pressure to join one faction or another, and the process of reform was suspended. The district used a four-stage strategy to respond to this dilemma. This included a shift to issues upon which agreement was less controversial, electing a centrist community member to serve as board chair, holding televised meetings of a strategic planning council, and reminding community members that stability and trust rather than disharmony were the district’s norms. In severe turbulence, the problems are so serious that normal administrative actions seem inadequate. A coordinated set of strategies is very likely needed, while business-as-usual thinking needs to be suspended.

• Extreme turbulence would mean serious danger of the destruction of the institution. Gross speculated that this degree of turbulence was possible, based on the fact that institutions do, of course, become unraveled. All of the 10 sites in the 1998 study were able to respond to their own cases of turbulence, ranging from light to severe, with success. However, ...