![]()

Part one

Extraordinary buildings, divergent readings

The first part of this book contains four close readings. They are readings of buildings and spaces designed by architects whose names are familiar from history books, practice monographs and journal articles; architects whose names have been admitted to the ‘canon’ of high culture because of their extraordinary projects. Where conventional architectural journalism can be over-generous to these famous architects and their ‘landmark’ projects – a phenomenon which Martin Pawley described as ‘the strange death of architectural criticism’1 – these essays show that close readings of architectural artefacts can yield interpretations which diverge from conventional wisdom, or from the rhetoric that architects use in relation to their own work.

The first chapter reads the CaixaForum art gallery in Madrid, reworked from a derelict power station by architects Herzog and De Meuron in a project celebrated by the global architectural media. It examines how the reworking embodies, simultaneously, the two key tactics used by post-war Western architects to make memorial architecture: the archaeological layering of building fabric; and the construction of ‘other worlds’ which aim to transport visitors into spaces of reflection. Reading the CaixaForum as a memorial, the chapter questions precisely what the gallery commemorates, and how its commemorative meaning might have shifted in the light of recent global events.

The subsequent chapter, by Edward Wainwright, concerns the Palace of Peace and Concord in Astana, Kazakhstan, a pyramid designed by architects Foster + Partners for President Nursultan Nazarbayev. The work of Foster + Partners is also fêted by the global architectural press, celebrated for consistently legible, transparent architecture across different building types and across the world. The pyramid – designed to house a triennial Congress of World Religions inaugurated by Nazarbayev in Astana – is clearly recognisable as a product of the Foster office. Wainwright examines how the pyramid is produced by, and produces, the rhetoric of transparency; and how it functions in projecting a post-Soviet national identity for Kazakhstan.

In Chapter 4, Suzanne Ewing reads a building by an architect who is, perhaps, a less ‘famous name’ than Herzog and De Meuron or Norman Foster, but whose work remains highly respected among professionals. She studies Sverre Fehn's Hamar Museum, exploring how the building reinvented its site. She examines how the architecture emphasises the ground and the horizon, encouraging the situation to be re-imagined as somehow more primal, the building somehow in immediate confrontation with the earth and sky. The site, Ewing argues, is never just found but is always invented in new ways by the architect. Indeed, she implies that the architect's cultural reading of the situation is a vital part of that process of invention.

Developing Ewing's interpretation of site, moving from the scale of the architectural object to the scale of landscape and climate – and echoing David Leatherbarrow's discussion of air and atmosphere – Jonathan Hill takes a journey from the ‘presumptuous smoake’ of seventeenth century London to the ‘very clear air’ of Houghton Hall and Holkham Hall in Norfolk.2 Houghton was the subject of the first architectural book dedicated to a single British house and, like its near neighbour, embodied the dialogue between nature and culture that became ‘one of the principal themes of the early eighteenth century’. One interior, the other exterior, Houghton and Holkham attest to the number of architectural authors at work. Seen in this light, authorship is multiplied and juxtaposed. Multiplied because, rather than a sole author, a number of authors are identified, including various designers, clients, builders and the weather. Juxtaposed because – sometimes competing, sometimes affirming – each authorial influence may appear to have informed or denied the others, in a conversation of various voices and unexpected conclusions.

These chapters raise important questions. To what extent can designers ever anticipate how their architecture will be read? Through a cultural reading of the situation, how can architecture come to re-invent its site? To what extent are canonical buildings produced out of their architect's rhetoric, and do they reproduce that rhetoric? Can architects who are immersed in one culture design successfully in another and, if so, how can they do it? Do architects inevitably reproduce their familiar cultural politics when they design, particularly when they are working in less familiar cultures? How do buildings attest to the multiple authors at work?

Notes

1Martin Pawley, The Strange Death of Architectural Criticism and Other Essays: Martin Pawley Collected Writings, ed. by David Jenkins (London: Black Dog, 2007).

2See also: Jonathan Hill, Weather Architecture (London: Routledge, 2012).

![]()

Chapter 2

An augury of collapse: Herzog and De Meuron's CaixaForum in Madrid

Adam Sharr

This chapter is about the CaixaForum art gallery in Madrid, a product of one of the world's most famous architecture brands: Herzog and De Meuron. Celebrated by the architectural media, the project was funded by – and bears the name of – Spain's largest savings bank. It opened in February 2008, at a time when the so-called ‘credit crunch’ was causing chaos in global financial markets. The CaixaForum was arguably the last major ‘signature’ project from the boom times to be completed before the recession hit in 2008, which many economists believe to have been the worst since the Great Depression of the 1930s.1 I will argue that the CaixaForum can be read, in retrospect, as an augury of collapse, as a curiously prescient anticipation of disaster.2

La Caixa buys a Herzog and De Meuron

La Caixa Group is Spain's largest savings bank and its third largest financial institution, with more than 5,500 branches. In 2008, it had a turnover of €411,522 million.3 Despite (or perhaps because of) its size, the organisation remains quick to highlight its corporate social responsibility, keen to point out its mid-nineteenth-century origins offering credit and savings facilities to poor families.4 In memory of these origins – La Caixa claims – it funds and controls the Caixa Foundation, Spain's biggest private foundation. According to the European Foundation, this is the fifth largest in the world in terms of budgetary volume.5 The Caixa Foundation runs a social welfare programme with four stated aims: ‘attending the main social problems [sic]; training for all kinds of groups; care and preservation of the environment; and, dissemination of culture’.6 Following this last commitment, it manages a large private art collection on behalf of the bank. This is exhibited free to the public at the CaixaForum gallery in Barcelona, the bank's home city, and also, from 2008, at the CaixaForum in Madrid.

The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu has argued that, in Western societies, the dominant realm of financial services – what he refers to as the economic field7- is approached in power and influence only by the fields of art and high culture.8 Power relations in all these fields operate similarly, he has claimed, crystallising around the competing consumption of goods, resources and values.9 Those immersed in the fields of art and high culture have tended to see banks as vulgar. But by trading in art – especially in contemporary art which can be portrayed as avant-garde – financial institutions have an opportunity to accrue a different sort of capital, distinguishing their cultural credentials.10 Banks can demonstrate good taste and perspicacious judgement with their art collections, which allow them to cultivate an image as magnanimous patrons. Moreover, art, as traded on the markets, has asset value and can be understood readily by bankers as a commodity like any other. Thus, just as some wealthy individuals acquire art works for their speculative commercial value and their potential to display cultural capital, so too do large organisations like banks.11 La Caixa seems to have been aware for some time of the potential for art and artists to embellish its self-proclaimed social mission and to broaden its reputation from fiscal expertise into high culture: it commissioned its logo from the artist Joan Miró in 1980, partly in a demonstration of Catalan patriotism but also as a display of cultural patronage.12.

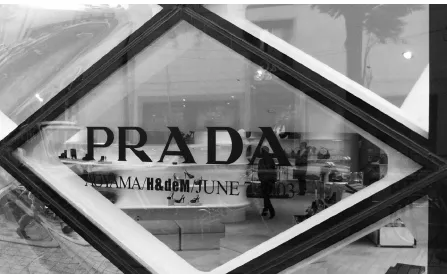

At this intersection of high finance and high culture, buying architecture as art is arguably as important as buying artworks. The architectural canon bulges with projects commissioned by financial institutions, from John Soane's work for the Bank of England in the eighteenth century to numerous twentieth-century examples including Richard Rogers’ Lloyd's of London and Norman Foster's HSBC headquarters in Hong Kong. Particularly in the post-war era, banks have bought work from famous architectural brands in order to bolster the cultural credit of their own brand. Herzog and De Meuron, distinguished by a litany of architectural awards including the Pritzker Prize in 2001, was clearly a reliable choice for La Caixa. Its work has had global reach and media appeal, attested by commissions such as the Tate Modern gallery in London, the Prada store in Tokyo's Ometesando Hills (Figure 2.1) and the ‘Bird's Nest’ Olympic Stadium in Beijing. The decision to buy an H&DeM was predictably unpredictable; the building would undoubtedly have both popular and expert capital as an edgy contemporary art object but it would also be delivered reliably, more-or-less on time and budget, with assured media attention. For both brand and cultural reasons, it was therefore no risk – or perhaps only the most reliable of risks – for the Caixa Foundation to hire Herzog and de Meuron for their new gallery in Madrid.

Figure 2.1 The H&deM brand alongside the Prada brand at their store in Tokyo's Omotesando Hills

Theatrical idiosyncrasies

The CaixaForum is conspicuously branded, displaying the bank's Miró logo in neon. It is set back from the Paseo del Prado – Madrid's famous boulevard of museums and galleries – and reworks the derelict Mediodía power station bought by La Caixa in 2001. The structure dates from 1899, designed by architect Jesús Carrasco-Muñoz Encina and engineer José María Hernández.13 It primarily comprised one large volume under two parallel pitched roofs, with thick walls in red brick sat on a rusticated stone plinth. By the time of its purchase – although it was disused and its roof was in an advanced state of disr...