1 Introduction

E.O. Wilson raised the ‘rallying cry for advocates of ecological restoration’1 in 1992 by writing that, ‘The next century, will, I believe, be the era of restoration in ecology.’2 Increasingly, ecologists are identifying a variety of ways to intervene in reducing or stopping environmental harm or ecosystem degradation. Globally states and private parties invest in large landscape restoration projects ranging from the reforestation of Rwanda to the reconstruction of depleted wetlands in the Gulf of Mexico. Ecologists, hydrologists and biologists have subscribed to the ‘era of restoration’ and have formed professional organisations such as the Society for Ecological Restoration with several thousand members that publish scientific journals such as Restoration Ecology to help the field continue to advance. More recently, social scientists and humanities scholars have contributed to restoration research with books on the economics of natural resource capital and the ethics of restoration.

However, before continuing on this cheery note it must be said that in darkness even a speck of light can be seen and admired. Let us explain why we have to suddenly cast a shadow on this positive start to this book. The amount of global ecological restoration work needed is daunting. At the end of May in 2016 the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) presented a report at a ministerial policy review session, which it titled Healthy Environment, Healthy People. In this report UNEP identified that:

15 out of 24 categories of ecosystem services are in decline … and four of the nine planetary boundaries (climate change, loss of biosphere integrity, land-system change, altered biogeochemical cycles (phosphorous and nitrogen)) have been crossed. Approximately 15,000 species (or 21 per cent) of global medicinal plant species are now endangered as a result of overharvesting and habit loss.3

The UNEP report observes that the effects of deteriorating environmental conditions on the health of people represent 23 per cent of the total human deaths globally.4 Despite its strengths, the report focused on the consequence of degradation for human health and did not cover, for instance, ecosystem losses. Species are disappearing at unprecedented rates and possibly faster than natural systems can adapt to these losses.5 The loss of what might otherwise be considered ‘redundant species’ has uncertain impacts because species loss may have influences on future buffering capacity for specific ecosystems against environmental changes.6 With these kinds of statistics and facts describing more a norm than an exception to the rule, humanity’s search for solutions and new ways of thinking about the human-nature relationship is, as one would expect, occupying much scholarly time.7

Ecological restoration is clearly making its mark as an intervention that aims to be holistic and capable of restoring self-sustaining ecosystems containing the characteristics of ‘past or least-disturbed landscapes’.8 The Society for Ecological Restoration has defined ecological restoration as ‘an intentional activity that initiates or accelerates the recovery of an ecosystem with respect to its health, integrity and sustainability’.9 Restoration is also a global proposition. In researching this book, the three authors residing in Australia, Belgium and the United States became aware of the Herculean efforts of hundreds and thousands of individuals reshaping landscapes to recapture lost or disappearing ecological values. Although the idea of ecological restoration is further discussed in Chapter 2, a few examples of ecological restoration initiatives will illustrate the potential and breadth of approaches that exist for restoring the natural environment. These examples illustrate the diversity of efforts that qualify as ecological restoration depending on the restoration goals for the project, restoration methodology and the types of actors involved.

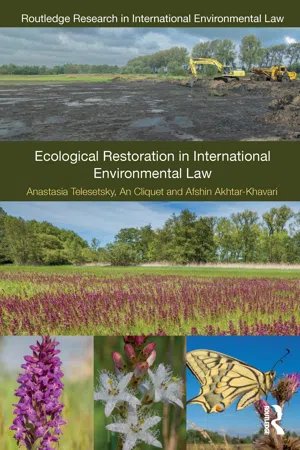

The pictures on the cover of this book, for instance, poignantly illustrate the potential of restoration, even in densely populated regions such as Belgium, with its highly fragmented and degraded natural heritage. They show the ecological restoration of a species of rich fen meadow and marsh relic. The project is situated in the lowland wetland nature reserve ‘Vallei van de Zuidleie’ (Flanders, Belgium). In the 1960s the area had been filled in with sludge from the dredging of the world-famous canals of Bruges, which were highly polluted in those days, and an impediment for tourism development. The wetland was also used as a dump site for domestic waste. In the period between 1992 and 2005 restoration work, financed by the Flemish government, removed the sludge and domestic waste down to the original peat soil surface and resumed the traditional mowing management without fertilisation. The management of the area is in the hands of ‘Natuurpunt’, a nature conservation non-governmental organisation (NGO), where both professionals and volunteers cooperate to manage the area. Shortly after the restoration work was finished, the compacted peat layer started to grow again. Highly endangered communities of plants characteristic of low-productive base-rich fen meadow and transition mire were able to recolonise the area including thousands of dazzling wild orchids. Some of the emblematic flora and fauna of the restored area is depicted on the cover of this book. Despite the positive results so far, restoration of hydrological conditions in the surrounding landscape, which have been highly degraded by intensive agriculture, will be essential to complete all restoration efforts and ensure a sustainable future for the area.10

In the United States, ecological restoration efforts have been ongoing for decades. For example, efforts started in 1934 at the University of Wisconsin Arboretum in the United States to re-establish an ‘original Wisconsin’ landscape that might reflect some of the landscape qualities that existed before European settlement. When the tall-grass prairie restoration project was initiated at the Arboretum, one of the early advisers was asked how long it would take to achieve restoration; the answer was ‘about a thousand years’.11 While subsequent scholars think a millennium might be optimistic, scientists and volunteers continue to invest their talents and time into this legacy project.12 At the heart of the Arboretum’s restoration, the 73-acre Curtis Prairie, named for one of the earliest champions of ecological restoration research, is the product of thousands of visionaries, experiments and hours of hard work including recruits from the Civilian Conservation Corps. A former working farm and pastureland, today the Prairie is home to 230 native species including delicate flowering gentians and orchids. The ongoing ecological restoration success of the Curtis Prairie has built momentum and the Arboretum is also investing restoration efforts in the 47-acre Greene Prairie, 14-acre Wingra Oak Savanna remnant and the 53-acre Southwest Grady Oak Savanna. Additional projects that seek guidance from Wisconsin’s past to create a future for Wisconsin where residents are connected with ecologically healthy landscapes are also under way for wetlands and deciduous forests. While these projects have achieved milestones, they also continue to face ongoing challenges including incursions of urban storm-water run-off and invasive species. Even so, the overall trend for restoration on sites such as the University Arboretum is positive. In a piece celebrating the 75th anniversary of Curtis Prairie, Wegener et al. queried whether it was accurate to state that Curtis Prairie is ‘restored’. They concluded that while ‘restoration is rarely finished … there is much to celebrate’.13 These sentiments capture the spirit of many working in the US ecological restoration efforts.

The breadth and range of restoration activities in Australia is remarkable given the size of the population in that country. An example is the approach taken to the Murray-Darling Basin (MDB) in Australia which is its largest river system with a total length of 1.061 million km2.14 The complex MDB waterways move through several Australian states making them jurisdictionally complex and very difficult to manage across political boundaries. The MDB is a critical resource for many competing stakeholders. For example, the Basin’s rivers have 16 wetlands in them listed under the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat (1971),15 making the ecological function of the river one of international significance.16 The river also sustains a very large number of communities along its length, including over 30 indigenous Australian nations. The MDB is significant for Australia’s economy. In 2005–6 a report by the Australian Bureau of Statistics indicated that 66 per cent of the water consumed in Australia for agriculture was in the MDB.17 All of these competing interests have led to an over-allocation of water with implications for the economy, livelihoods of communities and ecology (e.g. increased salinity) of the river and its riparian areas. In 2007, Australia adopted the Water Act (WA) to manage complex and often competing interests.18 While the WA’s primary purpose is managing the water resources of the MDB, the WA is also designed to restore the ‘ecological values and ecosystem services of the Murray-Darling Basin’.19 Given the size of this venture its success has yet to be properly realised. Buying water back from farmers – through a federal scheme – to sustain the long-term restoration of the river system and its riparian ecology is an important intervention and commitment to a very large and complex series of connected ecosystems.

While the operational details vary greatly in each of these examples, the general objectives for each of these projects is the same. So while on the one hand the Belgian and the American civil society managed projects offer discrete projects that reflect ongoing experimentation and the Australian government-led project covers a much more dispersed space for restoration, all of the projects are attempting to revive ecological values that have become compromised by human activities. While the approaches vary from physical removals of soils to annual burnings of grasslands to market transactions to ensure that water remains in the river system, all of the projects offer a means for reconnecting a variety of communities from indigenous groups to university students back to a functioning landscape. Negotiations among long-term and short-term human needs are at the heart of each of these projects as restoration proponents seek to explain the necessity of using heavy machinery in a place that appears natural, burning prairie grass in a community where fire is historically feared and re-allocating water from agricultural industry back to the river itself.

While each of the examples from Australia, Belgium and the United States should be regarded as a success story for ecological restoration, there is still much to be done to advance the ‘era of restoration’ heralded by E.O. Wilson. Some of the work will be technical work including developing best practices to manage invasive species, reversing trends of anthropogenic harm and designing large landscape projects that will remain viable over time given other ecological trends.

Other work will require changes in governance. This book argues that less global attention has been focused on developing appropriate governance for ecological restoration interventions through, for example, developing the law. As this book intends to demonstrate, while specific restoration outcomes will differ across the globe, there are key governance lessons that underwrite the success of ecological efforts that should be incorporated into restoration governance efforts. For example, ecological restoration efforts do not reside exclusively in the domain of science. While wetland biologists and hydrologists have the needed expertise to ensure success, there are also numerous cultural dimensions to restoration projects that require applying knowledge from social sciences and from communities. Law is one tool, albeit an often imperfect tool, in organising a governance structure for ecological restoration efforts.

Connecting ecological restoration and law

In theory, ecological restoration does not need law or lawyers. Ecologists such as the botanists and field scientists working at the University of Wisconsin Arboretum have made great progress in returning the vitality of the tall-grass prairies with no legal obligation to do so. Restoration efforts through projects such as the Curtis Prairie could continue on an ad hoc basis with only the occasional involvement of a policy decision-maker. After all, it could be argued that projects ultimately depend on the quality of restoration leadership rather than the quality of law.

While leadership definitely matters to the success of a restoration project, this book argues that it is too late given the extent of human impacts on the ecosystems now to simply pursue this ad hoc approach to restoration planning with each project being developed in isolation. There needs to be geographical connections made across projects to ensure that individual restoration efforts go beyond gardening initiatives that look aesthetically pleasing but fail to protect critical ecological values. Aldo Leopold sagely wrote that ‘If the biota, in the course of aeons, has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.’20 In practice, law should be a form of ‘intelligent tinkering’.

Law offers two specific advantages in the context of ecological restoration. First, it offers a driver for action to get parties to begin to ‘tinker’. States ‘tinker’ actively when they understand that they have obligations to engage in certain behaviour. The reason for mainstreaming environmental law and particularly international environmental law into restoration efforts is the potential of law to support the effective management of the recovery of the natural world. Environmental law can help coordinate, systematise and regulate conduct to both avoid and correct harm and damage.

This idea of environmental law as a ‘driver’ for active engagement in the environment is a recent development in the evolution of law. Environmental law began as a social tool to prevent certain activities such as seal-hunting or pollution dumping. It has only relatively recently evolved to operate as a common tool of protection with key areas set aside for restricted uses, such as wetlands of international significance. The transition of environmental law to creating rules of engagement with the environment will hopefully usher in a new era of norm...