eBook - ePub

Cell Biology of Trauma

John J. Lemasters, Constance Oliver

This is a test

- 384 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Cell Biology of Trauma

John J. Lemasters, Constance Oliver

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

This unique book presents an approach to viewing trauma. It examines the cellular consequences of trauma at a molecular level and provides new insights into the treatment of traumatic injury, based on cellular responses. The current of trauma research is reviewed, previously unpublished information on the topic is presented, and research directions are included.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Cell Biology of Trauma als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Cell Biology of Trauma von John J. Lemasters, Constance Oliver im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Biowissenschaften & Zellbiologie. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Stress Response and Wound Healing

chapter 12

THE STRESS RESPONSE AND STRESS PROTEINS

Martin E. Feder, Dawn A. Parsell, and Susan L. Lindquist

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. | Introduction | ||

II. | Inducible Stress Tolerance and Its Relationship to Stress Proteins | ||

III. | How Stress Proteins Function As Molecular Chaperones | ||

IV. | Regulation Of The Stress Response | ||

V. | Engineering Stress Tolerance | ||

Acknowledgements | |||

References | |||

I. INTRODUCTION

The stress response, or heat shock response, is a fundamental molecular mechanism with which organisms compensate for environmentally induced perturbations of cellular function. Heat and a variety of other stresses induce a suite of stress or heat shock proteins. These proteins play diverse cellular roles in minimizing or repairing damage due to stress, or in inducing tolerance to subsequent stress. Even in the absence of stress, these proteins or their close relatives are essential for a variety of cellular processes. Due to the vital nature of stress protein function and the importance of their induction as a model for gene regulation, interest in the stress response has undergone explosive growth, averaging more than 800 publications in the primary literature per year during the past five years. More than 500 publications examine the relationships between the stress response and the other subjects in this volume (e.g., reactive oxygen species, ischemia-reperfusion injury, inflammation). Accordingly, here we can but touch upon a limited number of aspects of the stress response that are relevant to the cell biology of trauma, and so can provide only a general introduction to the field. We will, however, cite many of the excellent recent reviews that provide entree to the primary literature.

II. INDUCIBLE STRESS TOLERANCE AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO STRESS PROTEINS

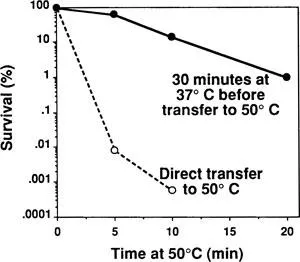

The general paradigm for inducible stress tolerance is this: If an unstressed cell or organism undergoes direct exposure to an extreme stress, cellular damage, if not death, will ensue. If, by contrast, the cell or organism first experiences a mild stress, it will become more tolerant of the extreme stress. Figure 1 exemplifies this phenomenon with data for yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) cultured at 25°C and then either transferred directly to a high temperature (50°C) or pretreated at a mildly elevated temperature (37°C) for 30 min before exposure to 50°C; pretreatment improves survival at 50°C more than 1000-fold.1 Similar data are available for a wide variety of cell types, species, and stresses.2–4

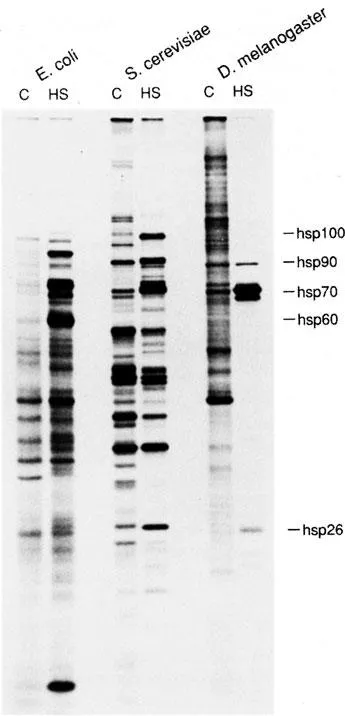

The mechanistic explanation of inducible thermotolerance began with the observation that exposure to heat induces puffing in the polytene chromosomes of Drosophila.5 Subsequent work established that the chromosomal puffing was a visible manifestation of the transcriptional activation of a characteristic suite of genes encoding proteins, originally termed heat shock proteins (hsps) (Figure 2). Several points are now evident:

• Hyperthermia is only one of many stresses that induce this same set of proteins. Known inducers of just one exemplary protein, hsp70, include high temperature, low oxygen (ischemia, hypoxia), ethanol, pH changes, H2O2 and other strong oxidants, free radicals, infection and inflammation, heavy metals, various toxins, ionizing radiation, extreme osmolar-ity, extreme levels of metabolites and normal intracellular regulators, cold, hemodynamic stress, and errors in protein synthesis, among others. For this reason, the terms stress protein and stress response are now in common use.

• Induction of stress proteins is a nearly universal feature of cells, and has been observed in every species in which it has been sought6 save one.7 Commonly, the induction occurs at environmentally appropriate levels of stress (e.g., the minimum temperature for stress protein induction is lower in fishes and insects from cold environments than in related organisms from hot environments).

• The major stress proteins can be assigned to at least five families or varieties of relatively large proteins (hsp100, hsp90, hsp70, hsp60, and Lon), and several more for smaller proteins (hsp27, DnaJ, GrpE, hspl0, and ubiquitin). Members of a family can be extraordinarily highly conserved. The human hsp70, for example, is 73% identical to the Drosophila protein and 50% identical to the Escherichia coli protein.

• Despite the ubiquity of the stress response and the conserved nature of stress proteins, organisms may vary considerably in their relative representation of particular stress proteins (Figure 2). In yeast, for example, hspl04 is one of the most prominent proteins induced by heat shock, whereas in Drosophila, expression of hsp70 predominates and a hsp100 family member is not evident. Members of the small hsp families, encoded by 30 to 50 different genes, dominate the response in many plants, whereas yeast and mammals synthesize only one small hsp.

The stress response initially attracted considerably attention as a model system for investigating gene structure and regulation. Exploitation of this model was highly successful: The genes for the Drosophila stress proteins were among the first eukaryotic genes to be cloned, to have their organization within the genome defined, to have their chromatin structure determined before and after activation, to have their regulatory sequences identified, and to have the transcription factors interacting with these sequences characterized. In addition, the stress response provided one of the first examples of selective gene expression operating at the level of translation. For a time, progress along these lines far outstripped efforts to understand the functions of the stress proteins themselves and the relationship of these functions to inducible stress tolerance. Since the mid-1980s, however, the application of molecular biological techniques and the emergence of novel hypotheses have set the stage for equal if not greater revelations concerning the function of stress proteins.

First, experimental studies have now demonstrated that stress proteins are not just correlated with inducible thermotolerance, but are essential for it. Deletion of the HSP104 gene in yeast, for example, results in a marked reduction in inducible thermotolerance, and introduction of the missing HSP104 gene on a plasmid restores inducible thermotolerance1 (Figure 3). Similar results have been obtained for hsp70 by varying cellular hsp70 levels either directly8,9 or through experimental manipulations of the corresponding genes.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Moreover, stress proteins have been shown to confer tolerance to many different forms of stress. Hsp104, for example, improves tolerance to ethanol and arsenite in yeast and is expressed constitutively in spores, the most eurytolerant stage of the yeast l...

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- The Editors

- Contributors

- Table of Contents

- Mechanisms of Lethal Cell Injury

- Cytoprotective Strategies

- Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury

- Stress Response and Wound Healing

- Preservation of Cells and Organs

- Index

Zitierstile für Cell Biology of Trauma

APA 6 Citation

Lemasters, J., & Oliver, C. (2020). Cell Biology of Trauma (1st ed.). CRC Press. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1639698/cell-biology-of-trauma-pdf (Original work published 2020)

Chicago Citation

Lemasters, John, and Constance Oliver. (2020) 2020. Cell Biology of Trauma. 1st ed. CRC Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/1639698/cell-biology-of-trauma-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Lemasters, J. and Oliver, C. (2020) Cell Biology of Trauma. 1st edn. CRC Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1639698/cell-biology-of-trauma-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Lemasters, John, and Constance Oliver. Cell Biology of Trauma. 1st ed. CRC Press, 2020. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.