eBook - ePub

Integrating Programming, Evaluation and Participation in Design (Routledge Revivals)

A Theory Z Approach

Henry Sanoff

This is a test

- 127 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Integrating Programming, Evaluation and Participation in Design (Routledge Revivals)

A Theory Z Approach

Henry Sanoff

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

First published in 1992, this book is about making connections that may lead towards a new professionalism, since the past several decades have given rise mainly to new kinds of specialists in the areas of programming, evaluation, and participation. The implications for such integration are far reaching, with profound future effects on the physical environment, the design professions, and the education of designers. The book is split into four sections dealing with facility programming, several forms of evaluation, participatory design, and the application of Theory Z principles. This book will be of interest to students of architecture and design.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Integrating Programming, Evaluation and Participation in Design (Routledge Revivals) als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Integrating Programming, Evaluation and Participation in Design (Routledge Revivals) von Henry Sanoff im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Architecture & Architecture General. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

1 Facility programming

Programming is generally viewed as an information processing system setting out design directions that will accommodate the needs of the user, the client, the designer, or the developer. The nature and scope of design decisions and design information have changed rapidly, and the role of programming has thus changed as well. The uses of programming have been extended from primarily acquiring and organizing information (Heimsath, 1977) to investigating and developing information, analyzing client and user needs, and evaluating projects after construction and occupancy (Freidman, Zimring, & Zube, 1978; Wener, 1989).

Programming has been seen as a valuable resource for a systematized process that provides a structured framework for accumulating and classifying data. As an analytical process, it encourages decision making through objective procedures rather than on individual assumptions or personal prejudices. A report by the Building Research Board of the National Research Ciouncil (1986) on programming practices states that 'programming services may not always result in new construction or changes to the physical building, but in organizational or managerial changes that achieve the same objectives' (p.1).

There is considerable diversity in the use of the terms space programming, facility programming, and functional programming and in their meaning within the design professions. In addition to the differing terms that identify programming, there are also philosophical differences regarding the of programming. Expressions such as 'programming is design, programming is not design,' and 'programming is getting ready for design,' underlie the diversity of purposes and places of programming in the design process.

Everyone, however, would accept the view that a program is the organized collection of specific information that involves developing, managing, and communicating. Most will also agree that programming is the process of identifying and defining the needs of a facility. Although general features have emerged, programming should be recognized as a dynamic and interactive process.

The basic references for programming lie in the published volumes of Palmer (1981), Pena (1977), Preiser (1978, 1985, 1992), Sanoff (1978), and White (1972). The principal objective of Preiser's edited collection Facility Programming (1978) and Programming the Built Environment (1985) is to provide an authoritative overview of the user-oriented programming approaches that are currently to be found at work in architectural and environmental design. Both books describe the professional programming activity conducted by architectural and programming firms. The topics covered range from problem definition, cross cultural programming, and post-occupancy evaluation to adaptive reuse and other more specific examples of programming. Each chapter is largely self-contained and represents various attitudes about programming and about the breadth, scope, and prospects of the field.

As a complement to the Preiser volumes, Sanoff's Methods of Architectural Programming (1978) is about the technical aspects of programming. Here the material moves from data-gathering techniques, through methods of synthesizing and organizing data, to a field application of programming techniques that makes use of user expertise. The volume stresses a general flexibility of approach, in which the techniques may be combined and merged, depending on the situation on hand.

Palmer's Architects Guide to Facility Programming (1981) covers much of the same ground as the Preiser and Sanoff volumes, though attempts to integrate information-gathering techniques with case studies. Although it was written 3 years latter than Sanoff's book, it fails to show the development of facility evaluation studies and their relationship to facility programming.

By contrast, Pena's Problem Seeking (1977) is a presentation of one approach, the CRS (Caudill, Rowlett, and Scott, Architects and Planners) method of programming. The five-step process is presented in lock-step fashion with partially worked examples. Rather than adopting a flexible attitude toward the organization of information, the book views the role of the programmer as being conformity to a predetermined format.

In an effort to bridge the theory-practice gap, White (1982) conducted interviews with architects to assess their attitudes toward programming practice. In an open-ended telephone survey of 73 architects in the United States, programming strengths were described by the respondents as including 'thorough rigorous analytic process, strong client/user participation, programming tailored to each project, strong integration with design and successful projects, and happy clients.' The recurring programming problems were reported to be 'finding the true needs of the client, getting clients to make decisions, and clients don't appreciate programming at program-design connection' (p.37).

According to White (1983), clients are frequently unaware of their needs and sometimes are impatient or do not understand why the information is needed. Some clients will not permit the staff to participate in the programming process. There are also occasions when the client says one thing and the programmer hears another; the client often faces difficult choices and is not prepared to work as quickly as the process requires. These difficulties cited by practitioners clearly suggest the need for considerable improvement in communication with the client, as well as collaborative involvement in the programming process.

When asked about the reasons for offering programming services, beyond providing a better building, the respondents in the White study said that such a service 'facilitates the design process, marketing, project management tool, client confidence in project and firm, and saves client and firm time and money' (p.52). The majority of architects agreed that programming provided the client a way to participate in the project's planning process. They also indicated that programming leads to improvements in the client's operation; therefore, programming firms sometimes serve also as management consultants. Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum (Silver & Klein, 1985) described the programming process as being able to 'promote confidence, teamwork and consensus; convey a sense of care and attention to users; minimize space-allocation abuses; and leave a clear trail of decisions and approvals for superiors to review' (p.3).

Comparing programming models

Architectural programming is not a rigidly defined process. Each programmer has his or her style and emphasis, and each project requires a certain amount of custom fitting of any model that a programmer may have. Because a number of programmers have described their approach, the purpose of this section is to examine seven of these approaches, to compare their similarities and differences, and to combine them into a composite model.

The seven models

The models reviewed are by Davis & Szigetti (1979), Farbstein (in Palmer, 1981, p.33), Kurtz(in Preiser, 1978, p.41), McLaughlin (1976, p.42), Moleski (in Palmer, 1981, p.37), Pena (1977, p.43), and White (1972, p.44). These authors were selected because their programming work is documented in the literature and they follow a well-delineated process.

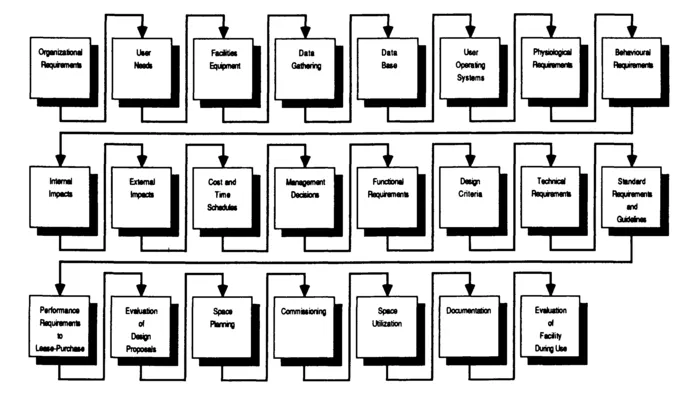

Gerald Davis. Davis's programming model (Davis & Szigetti, 1979) is a 21 step process (Figure 1.1) that begins with preprogramming and moves through evaluating the facility in use. It is directed toward the planning of corporate facilities. The first part of the process, as with Moleski and Kurtz (below), is to become familier with the client's business organization, operation, activities, and needs, both present and long range. The programming steps include gathering data on the operating facilities; on physiological needs, such as those affecting health, safety, and performance; and on behavioral requirements, such as those affecting motivation, learning, and attitudes. The impact of the project is evaluated in terms of its effect on the functioning of the organization as well as its effect on the community and the environment. Cost estimates are made, and essential criteria for design are established. Throughout the design process, the programmer provides feedback to the designer. After the facility is built, the programmer assists management in moving into the facilities, and in their fine tuning. The facilities are evaluated after they have been in use for a period of time, usually within 6 months.

Figure 1.1 Davis's programming process

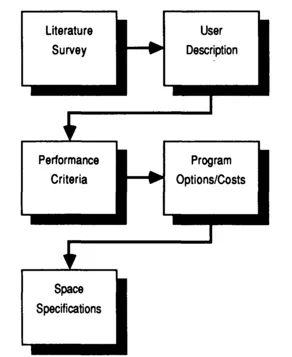

Jay Farbstein. Farbstein's process (Palmer, 1981) consistes of five steps (Figure 1.2) that identify client needs. His first step is to search the existing literature for information on the building type. The next step is to identify the users of the facility and their activities, attitudes, and characteristics. Then performance criteria are established for area needs, circulation, ambient environment, safety and security, surfaces, finishes, flexibility, and site design. After the client reviews the performance criteria, the design issues are identified, the program options are identified for each issues, and each option is measured in terms of costs, benefits, and trade-offs. The client is consulted again to assess the options. Space specifications and adjacency relationships are developed. Finally, the client is consulted once more for approval of the program and the budget. Farbstein's recent work (1985) stresses the periodic assessment of the facility's performance after occupancy.

Kaplan, McLaughlin, Diaz (KMD). McLaughlin (1976) of KMD believes that programming is design, and that evaluation is an integral part of the design process. KMD's programming procedure consists of three phases (Figure 1.3), the first of which includes identification of the user, the user's organizational philosophy and objectives, and the financial feasibility of the project. The second phase considers the client's openness to new ideas, the physical context, a functional analysis, and aesthetic demands; this phase includes a survey of building types and all factors that may influence the form and content of the building. The final phase corresponds more closely to what is typically referred to as project development, in which studies of building organization, schedules, outline specifications, and budgets are conducted. McLaughlin and KMD also follow a three-phase process of evaluating their buildings that begins in the programming stage of the project, with an exploration of the future occupants' expectations of the new facility. After the building has been occupied for several months, another survey of user expectations is conducted. The third survey of the users occurs after they have adjusted their work processes to the new facility.

Figure 1.2 Farbstein's programming process

John M. Kurtz. The programming model presented by Kurtz (Preiser, 1978) emphasizes iterative programming, which continues into the design phase (Figure 1.4). Kurtz's belief is that generalized long-range programmatic decisions should be made at the beginning of a building project. The first step in this model, as in that of Moleski (below), is for the programmer to be familiar with the client's operation, philosophy, and objectives. The basic program includes a literature search on the building type, a determination of the client's operating requirements, and a preliminary program of the building's organization, space sizes, and relationships. The basic program is presented to the client for feedback, and the program is revised and presented again until general agreement is reached. The design phase is considered part of the programming process because the client continues to provide feedback in reviews and revisions of preliminary designs.

Walter H. Moleski. Moleski's approach (Palmer, 1981) consistes of four stages and two intermediate reviews with the client, the architect, and the programmer (Figure 1.5). The activities are (1) awareness; (2) diagnosis: (3) first review; (4) strategy; (5) second review; and (6) action. Initial familiarity with the client's operation occurs in Step 1, through reviews with the client and through interviewing the client to de...

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Section 1: Facility Programming

- Section 2: Evaluation

- Section 3: Participatory Design

- Section 4: Applying Theory Z Principles

- References

- Index

Zitierstile für Integrating Programming, Evaluation and Participation in Design (Routledge Revivals)

APA 6 Citation

Sanoff, H. (2016). Integrating Programming, Evaluation and Participation in Design (Routledge Revivals) (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1640659/integrating-programming-evaluation-and-participation-in-design-routledge-revivals-a-theory-z-approach-pdf (Original work published 2016)

Chicago Citation

Sanoff, Henry. (2016) 2016. Integrating Programming, Evaluation and Participation in Design (Routledge Revivals). 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1640659/integrating-programming-evaluation-and-participation-in-design-routledge-revivals-a-theory-z-approach-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Sanoff, H. (2016) Integrating Programming, Evaluation and Participation in Design (Routledge Revivals). 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1640659/integrating-programming-evaluation-and-participation-in-design-routledge-revivals-a-theory-z-approach-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Sanoff, Henry. Integrating Programming, Evaluation and Participation in Design (Routledge Revivals). 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2016. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.