eBook - ePub

Morphology and Universals in Syntactic Change

Evidence from Medieval and Modern Greek

Brian D. Joseph

This is a test

- 334 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Morphology and Universals in Syntactic Change

Evidence from Medieval and Modern Greek

Brian D. Joseph

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

This book, first published in 1990, is a study of both the specific syntactic changes in the more recent stages of Greek and of the nature of syntactic change in general. Guided by the constraints and principles of Universal Grammar, this hypothesis of this study allows for an understanding of how these changes in Greek syntax occurred and so provides insight into the mechanism of syntactic change. This title will be of interest to students of language and linguistics.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Morphology and Universals in Syntactic Change als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Morphology and Universals in Syntactic Change von Brian D. Joseph im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Langues et linguistique & Linguistique. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Chapter 1

The Question of Methodology

Before beginning the pre-theoretical section, it is important to consider two methodological aspects of historical syntactic research, especially with regard to establishing synchronic analysis in a language like Greek, attested only in texts for some stages. In particular, one must consider why studies in historical syntax are possible, given the necessary substitution of textual evidence for the judgments of native speakers as the primary data, and also why the Greek textual corpus, especially that of Medieval Greek, can provide these primary data.

1. On Doing Historical Syntax

Detailed syntactic analysis, as is obvious from a brief look at any generative-syntactic work, generally requires access to the intuitions of native speakers as to the acceptability, synonymy, etc. of a variety of sentences, carefully constructed to test certain hypotheses about the structure of a given construction. The proper analysis of isolated sentences is often indeterminate—it is only when additional facts are adduced that the correct analysis becomes clear, and particular hypotheses are confirmed or disproved. Furthermore, the necessary judgments are often quite delicate.A

For example, the sentences of (1), by themselves, are indeterminate as to their respective underlying structures, and in fact, are quite similar in their surface structures:B

- (1)

- Jane was easy for us to take advantage of.

- Jane was ready for us to take advantage of.

However, there are deep structural differences between the two which can only be brought out through a consideration of additional facts such as (2) and (3):

- (2)

- To take advantage of Jane was easy for us.

- Taking advantage of Jane was easy for us.

- It was easy for us to take advantage of Jane.

- (3)

- *To take advantage of Jane was ready for us.

- *Taking advantage of Jane was ready for us.

- *It was ready for us to take advantage of Jane.

or the rather delicate distinction between (4) and (5):

- (4)?Advantage was easy to take of Jane.

- (5) * Advantage was ready to take of Jane.

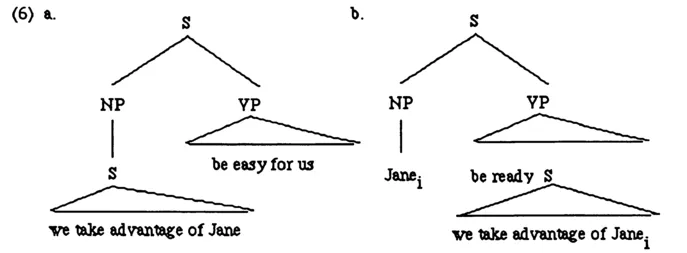

The effect of all these additional data is to establish (6a) as the structure underlying (1a) and (6b) as the structure underlying (1b):

Sentence (1a) is derived by a raising rule making the subordinate clause object, Jane, into the subject of the main clause, and (1b) is derived by a rule deleting the subordinate clause occurrence of Jane under identity with the main clause subject, Jane.1

The obvious problem with doing research on historical syntax, then, is the lack of access to the complete range of data that may be necessary to confirm or disprove a particular analysis. The crucial grammatical sentences may not occur in the corpus of texts for various reasons--the absence may be accidental, due to the subject matter, induced by the low frequency of the particular sentence-type in speech, etc. Furthermore, texts in general do not contain ungrammatical sentences,2/C so crucial ungrammatical sentences may never be available as data.

Despite these problems, though, it is possible for meaningful work in historical syntax to be carried out. In the first place, the texts do provide a limited range of data, from which it is generally possible to learn much about the general framework of the syntax of a language. In particular, the possible surface syntactic constructions of a language can be identified from textual evidence. When the goals of a work do not involve finely detailed syntactic analysis, these data may well be adequate.D In addition, when there is sufficient attestation, textual evidence allows for the use of statistical counts in making judgments of acceptability. This is especially so when a dischronic change is reflected in a significant variation in the ratio of the use of one surface configuration to another—as Ebert (1976: xi) puts it: "Quantitative analysis of variation may provide support for positing a significant difference in rules while there is but little change in surface forms."

Furthermore, the identification of the surface constructions of a language can sometimes lead to deeper analyses once data from other languages, i.e. language-universal considerations, are added. It is often the case that many languages which are readily accessible provide evidence that a predicate with a particular meaning can participate in a syntactic process. If the surface result of that process appears with that predicate in a less-accessible language, the claim can be put forth that that language possesses that syntactic process.

Such universal considerations are of help when one is faced with a surface construction whose underlying structure may be indeterminate, for they enable one to maintain that a particular analysis is the best available hypothesis, especially when no evidence exists to contradict it. For example, if a sentence such as (1a) is found in a text, with that language's word for EASY, and the surface nominal corresponding to Jane has the properties of the subject of the main clause, then an analysis of that sentence as being derived by the raising rule described earlier can be supported as the best available hypothesis, as opposed, for instance, to the deletion analysis proposed for (1b), because the adjective EASY triggers that raising process in many languages, including English, French, Yoruba, and others. Of course, any "hard" evidence, such as the existence of sentences corresponding to (2), is to be preferred, but even in the absence of such evidence, one can often put forth a particular analysis, with some degree of certainty, on semantic grounds.

The line of argumentation for and supporting of particular analyses is intimately linked to a general view of linguistic theory in which semantics and syntax are closely inter-related. The claim is that a particular predicate, either verbal or adjectival, because of its semantic features, MUST occur in a particular structural frame underlyingly, and that this is true for all natural languages and for all speakers of natural languages.3 Such support for analyses must be used with caution, though, for it is not always clear which specific linguistic features belong in such a universal grammar. Still, the indications from other languages are often strong enough to point toward one or the other analysis for a specific indeterminate sentence in a text.E

Therefore, in a very limited sense, ANY language can serve as a control over syntactic analyses of a language-stage accessible only through texts, since Universal Grammar must be sufficiently general to accomodate facts from any natural language. Even more important, though, in the study of the more recent stages of Greek is the fact that the modern language is available as a control. Languages tend not to change radically over relatively short periods of time,F and genetically closely related languages tend to share certain syntactic features.4 Modern Greek, therefore, as the immediate descendant of Medieval Greek,5 is especially useful for gaining insights into particular problems of analysis for earlier stages of Greek. Furthermore, most Greek scholars agree that Greek took on its essential form as "Modern Greek" by no later than the 16th century, so that Modern Greek is particularly well-suited as a control over Medieval Greek. For example, Costas (1936: 95) writes: "By the end of the 15th century the popular language had acquired most of the peculiarities which characterize it today."

In addition to hard textual evidence and semantic considerations, there is another factor that can facilitate diachronic syntactic research. As is well-known, non-native speakers of a language who have studied that language thoroughly can have veiy clear judgments about the grammaticality of sentences in that language. For example, from reading the corpus of Medieval Greek texts, one cannot help but gain an understanding of the way the language works, a "Sprachgefühl", which enables one to make educated guesses about how sentences were constructed at that time, which sentences were acceptable, and so forth.6/G

The net effect of all these factors, therefore, shows that it is possible to make good use of textual attestations without having to rely solely on the presence or absence of a particular sentence in the corpus, in carrying out historical syntactic research.H In general, then, it is possible to do historical syntax, even though the unavailability of native speakers of the relevant historical stages of a language admittedly can hamper investigations.I

2. Historical Syntax in Greek

With regard to the question of carrying out historical syntactic work in Greek, it is important to note that one is fortunate in having ample attestation and description for the early stages of the language, Classical Greek and Biblical (Old Testament and New Testament or Koine) Greek. In particular, there are numerous texts from these periods, numerous thorough descriptive grammars,7 several good lexicons,8 in some cases concordances,9 and so forth. These research tools make it possible to investigate the syntax of particular words and constructions. These resources were used to the fullest extent possible in the preparation of this thesis and form the basis for any claims made regarding Classical and Biblical Greek syntax.

With regard to Medieval Greek, though, the same wealth of texts and of descriptive materials is not available to the researcher. There are no good descriptive grammars of Medieval Greek compiled according to modern descriptive principles,10 although a few good works do exist on specific questions of Medieval Greek grammar,11 and the only Medieval Greek lexicon, that of Kriaras (1969 et seq.), is only complete through the second letter of the Greek alphabet at present.J Therefore, in order to be able to make claims regarding Medieval Greek syntax with any degree of authority, it was necessary, in doing the research for this thesis, to read through the corpus of relevant Medieval texts.

This, however, leads into what is perhaps the major problem in doing historical syntactic work in Medieval Greek--the nature of the texts. Although the number of texts from the Medieval period is staggering, not very many can be considered to be representative of vernacular Greek of the period in which they were written. The crucial question, then, concerns the reliability of the textual evidence as an indication of the possible forms and sentences of the spoken language.

The problem of the nature of the texts is one which is present throughout the history of Post-Classical Greek. Because of the overwhelming cultural influence of Classical Greece, Greek writers in Post-Classical times felt compelled to emulate the language and style of the Classical writers. This Atticizing drive resulted in the writing of many Medieval texts, in what can be called a "learned" style, which were virtually indistinguishable linguistically from the Greek of over 1,000 years before their time. This same force was behind the so-called "Language Question" of the 19th and 20th centuries in Greece, in which much political, social, and educational energy was expended in the battle between proponents of the archaizing, puristic, and largely artificial language (the so-called "Katharevousa") and those of the popular, vernacular language (the so-called "Demotic")11 Despite this Atticizing movement, though, there are many Medieval works written in an approximation of the spoken language of the period, although even these texts show signs of influence from the learned language. Therefore, even though no text reflects all the possible elements of the spoken language, there is still a fairly large collection of vernacular texts from the late Medieval period. And, there is considerable agreement among scholars as to which texts belong in this category.12

Browning (1969: 14-15; 78-79) briefly describes this corpus as follows:L

In the later medieval and early modern perio...