![]()

1 Introduction

Public—private partnership in turbulent times

Graeme Hodge and Carsten Greve

Introduction

One of the paradoxes of the last few decades has been the continuity and even growth of infrastructure public–private partnerships (PPPs) despite the loud voices of critics and harsh judgements of some academics. Indeed, there is little doubt about the success of PPPs on the basis of global interest, the frequency of use in countries such as the UK and Australia or by the spectacular delivery of timely new infrastructure. There has been substantial work undertaken to date on the multiple meanings of PPP more generally, the multidisciplinary languages spoken by commentators, and on the evaluation challenges faced by those interested in assessing PPPs as projects or activities. Whilst acknowledging the considerable advocacy and assertions of those pushing such reforms, there has been less work undertaken on the theory of PPPs. There is a real need to articulate the potential causal factors behind why PPPs may be capable of producing superior performance compared to traditional arrangements. It is to this purpose that this book is dedicated. This chapter focuses in particular on meanings given to how PPP might be judged as successful by implementing governments, and it tries to bridge the gap between what analysts purport to ‘know’ and how advocating political actors behave. The specific aim of the chapter is to explore the notion of success – what constitutes success for PPP? The criteria appear to be both varied and multifaceted, while also mirroring the very goals of government in society. A recent contextual factor has been the global financial crisis (GFC) that hit the world in 2008, catapulting PPP into ‘turbulent times’. So how might the aftermath of the GFC affect PPP success?

The chapter is divided into three parts. Part one examines the variety of forms and levels of PPP. Part two details the theoretically-based criteria for ‘success’, taking inspiration from some of the recent literature on ‘policy success’. Part three explores what the GFC and the turbulent times that have followed it may mean for PPPs. The structure of the book is then presented and finally, a conclusion on how to theorize about success of PPPs is offered.

Public—private partnerships: a variety of forms and levels

PPP has been defined as ‘cooperation between public–private actors in which they jointly develop products and services and share risks, costs and resources which are connected with these products and services’ (Van Ham and Koppenjan 2001: 598, quoted in Hodge and Greve 2005). Moreover, authors such as Weihe (2005) and Hodge and Greve (2007) have defined partnerships as encompassing several different families of activities; and the desire to articulate public–private partnership continues. Thinking about infrastructure partnerships, for example, a recent OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) report defined PPP as ‘an agreement between government and one or more private partners (which may include the operators and the financiers) according to which the private partners deliver the service in such a manner that the service delivery objectives are aligned with the profit objectives of the private partners and where the effectiveness of the alignment depends on a sufficient transfer of risk to the private partner’ (OECD 2008: 17). While this definition has some advantages, it does not include the non-profit sector where voluntary organizations co-operate with the government, and is therefore limited.

In the United Nations, PPPs are defined as ‘voluntary and collaborative relationships between various parties, both state and non-state, in which all participants agree to work together to achieve a common purpose or undertake a specific task, and to share risks and responsibilities, resources and benefits (UN General Assembly 2005: 4; cited in Bull 2010: 480). Such partnerships can include those oriented towards resource mobilization, advocacy and policy goals, as well as long-term operations.

There are several crucial concepts here. One concept is ‘risk’. In almost all definitions, sharing of risks in an explicit way is mentioned as one of the key aspects of PPP. This differs from earlier ideas on risk sharing through contracting out/outsourcing arrangements where this was more implicit.1 Another key concept is ‘innovation’: the public sector and the private sector have to come up with new solutions and ‘work together or achieve a common purpose’. More is expected of PPPs than just ‘ordinary’ collaboration. There is usually a sense of hope that the relationship is a long-term one – and desirably longer than the temporary relationship achievable through traditional ‘contracting out’ of services. Additionally, many partnerships entertain the notion of a certain degree of power sharing whilst working together jointly.

As witnessed in the last few decades, PPPs come in many shapes and sizes. Perhaps the most visible form of recent partnership has been the long-term infrastructure contract (LTIC) partnership. The LTIC partnership is organized around a design, finance, build, own, operate, transfer model and involves private-sector financing and private-sector project management capabilities. Historically, too, the urban development and downtown renewal experience of the US from the 1960s onwards saw close redevelopment partnerships as a visible and important PPP form (Bovaird 2010: 50). Another is the widespread co-operation between governments and non-profit organizations. This has been a tradition in some countries, especially in the USA where non-profit sector organizations run many public services (Amirkhanyan 2010; Kettl 2009). In the UK, there has been a debate on the ‘big society’ since Prime Minister David Cameron took office. Recently, the ‘big society’ has also been suggested as a guide for research efforts, though universities express misgivings about that (The Guardian, 27 March 2011). There are also other newer forms of partnering where the public sector and the private sector team up in new innovative formats to solve common challenges. ‘Gate21’ is a current example of a partnership on environmental issues. What began as a sustainable future forum by local government quickly spread as relationships were forged with other local governments, private sector companies and non-profit organizations as well as universities and housing associations (www.gate21.dk).

PPPs are, moreover, found at various levels of government, from regional partnerships between local governments and local private sector companies or associations, to national governments that team up with national companies or associations, to international organizations that team up with multinational companies (Skanska) or associations (the Red Cross). There are, of course, a number of combinations possible within that framework (Donahue 1989). Some challenges arise when local governments try to deal with global partners or when national governments want to form partnerships with multinational companies.

PPPs are also, clearly, more than projects (the building of a hospital or bridge). PPPs are now also associated with policies on how the government should interact with the private sector in order to improve public services or create innovation (the recent Danish government’s ‘Strategy for public–private partnerships and markets’ is an example of this). At the UN level, there is a PPP policy (Bull 2010). At an even broader level, PPP could be a metaphor or a brand for how governments want their interaction with business and society viewed, or, alternatively, how they want the role of government in the economy viewed. And at a broader level still, the UN’s Millennium Declaration (and the subsequent establishment of the Millennium Development Goals, MDGs) saw partnership being used in the context of developed countries having a role in aiding developing countries; Goal 8 here was to achieve a ‘global partnership for development’ through various means.2

Perhaps it makes sense to view PPP as being understood at many different levels. Hodge (2010b) formulated it in this way:

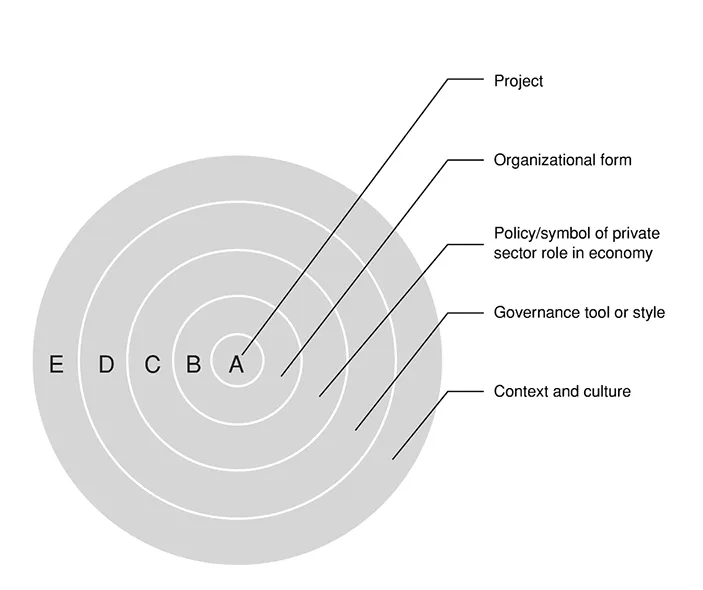

PPPs can be understood as (1) a specific project or activity, (2) a management tool or organizational form, (3) a policy, or statement as to the role of the government in the economy, (4) a governance tool or symbol, or (5) an historical context and a cultural set of assumptions.

A conceptual model of the PPP phenomenon

So PPP may indeed mean different things to different people. If this is the case, how might we build on this idea and develop a conceptual model in order to contribute to multiple jurisdictions and PPP debates around the globe? Considering just the infrastructure family of PPPs for the moment, we might view LTIC-type PPPs to provide infrastructure through a series of lenses: from a narrow lens at one extreme to the broadest lens at the other.3 We might view PPP as a specific infrastructure project; as a management or project delivery reform; as a government policy or a symbol of a strong and capable private sector role in a mixed economy; or, more broadly again, as a tool in a modern governance task, as shown in Figure 1.1. Also shown is the underlying notion that all four of these perspectives of PPP exist within the context of a broader national history and set of cultural assumptions.

At the narrowest level, A, PPP is viewed as a single project. At level B, PPP is viewed as a specific type of infrastructure delivery mechanism involving the use of contracted private finance to initially fund all works. It is, under this view, a project delivery tool, and one in which private financing incentives encourage excellent project performance and early delivery. This view is typical of the engineering and project finance disciplines, but despite being common, its narrowness is rarely acknowledged.

The next conceptual level, C, takes this project tool one step further and sets the private finance delivery of PPP infrastructure as a policy preference for a

Figure 1.1 Dimensions of the public–private partnership phenomenon

Source: Adapted from Hodge (2010b)

jurisdiction. It may also operate at a wider policy level and recognizes explicitly that there is, in reality, not one single PPP type but a wide variety of alternative project delivery options available to governments, all of which use differing arrangements of public and private sector skills. The OECD list of acronyms is a manifestation of this: the breadth available here4 is therefore essentially a policy statement that the private sector has a valid – and indeed major – role to play in today’s mixed economy, whichever technical delivery option is chosen.

Broader again in this conceptual model, level D represents the inherent political or governance dimension PPP has always had. For example, the use of huge private contracts with a consortium for the delivery of high-profile government projects is a strong regulatory tool in governing.5 Large economic incentives can be employed to ensure that the promise of early achievement of government objectives is met – even for complex projects and in controversial circumstances. PPPs can also function as a broader governance tool and mark a particular style of governance. For instance, the Labour government in the UK throughout the 1990s struggled to develop its relationship with the City of London. But as Hellowell (2010: 310) points out, PPP provided the incoming Tony Blair and his ‘New Labour’ government with advantages. Indeed, the use of private finance had the ‘crucial [political] advantage that borrowing undertaken through it did not score against the main calculations of national debt’, and borrowing was thus essentially ‘invisible’ to public sector borrowing and investment measurements. Blair’s rebranding of the Private Finance Initiative (PFI) scheme as a public–private partnership policy was a further masterful political move under the ‘third way’ banner. Importantly, this PPP policy not only assisted New Labour in establishing a stronger relationship with the City of London, but also international promotion of PPP ideas then enabled this relationship to be cemented (Hellowell 2010). Both of these political characteristics of PPP suggest that it continues to have an inherently political, and thus governance, context in addition to any functional engineering or economic meaning.

In this model, each of the inner perspectives of PPP exist within the context of others. The notion that a PPP is simply a project delivery tool, for instance, carries with it many assumptions: the role of the private sector in the economy, how governance might occur in a country, as well as broader historical and cultural assumptions of that country. These dimensions are, to a strong degree, inherently bound together.

In this conceptual framework it is import...