![]()

1

Origin Stories of Revolution, Exorcisms of the Past

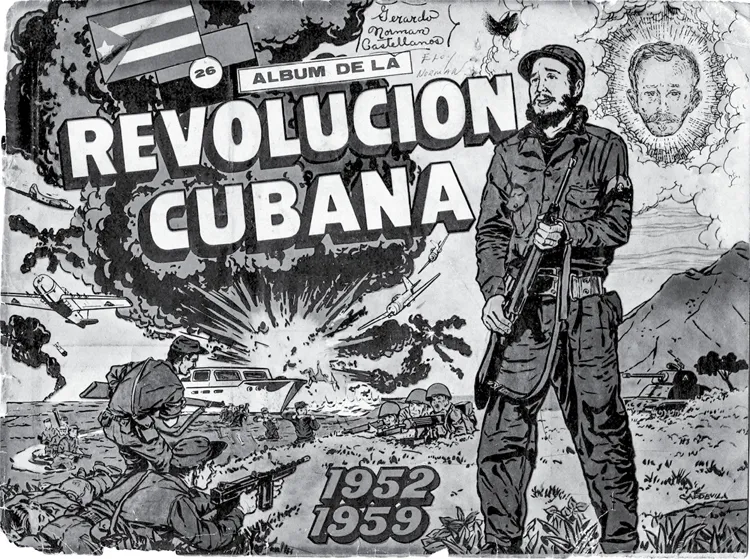

Many Cubans know it. Thousands of visitors to the island have seen it too. Sold daily in Havana curio markets in countless imitation copies, the 1959 Album de la Revolución Cubana (Album of the Cuban Revolution) offers the perfect souvenir of radical kitsch. As comic-book supermen, Fidel Castro and militants of his 26th of July Movement appear fit for child’s play, members of a toy army dressed in toy fatigues. For the tourist, the drawings reinforce an image of Cuban history as an improbable epic that is simultaneously quaint. The storyline seems inspiring but almost make-believe.

Yet, despite its status as a common traveler’s collectible today, the original Album de la Revolución Cubana is a remarkable historical document.1 Partnering with a private sweets company in mid-1959 (the Compañía Industrial Empacadora de Dulces), writers at the Havana-based Revista Cinegráfico S.A. (or the Cinematic Graphics Review Corporation) crafted a slim publication of thirty-plus pages with 268 blank spaces. Those spaces, in turn, were meant to be filled by cartoon cards depicting episodes of revolutionary resistance, which could only be aquired by purchasing cans of Felices brand jams. So popular were these postalitas as collectors’ items that Zig-zag, the island’s leading humor newspaper, dedicated a two-page cartoon spread to poking fun at the obsession.2 History sold well in the heady days of 1959, even as Cubans threw themselves headlong into the promise of a bold new future. Emblazoned on the album’s interior title page, the slogan “Consume Cuban Products” advertised a brief, and today largely forgotten, juncture when private capital, middle-class consumers, and the incipient revolutionary government worked as a team.3

But if the storyboard squares hint at how quickly insurgent legend seeped into island society’s every pore, the particular fable they told reveals much about the changing shape of Cubans’ interpretations of their past over time. On the one hand, the album manifested the power of a revolutionary movement whose guerrilla leaders and student allies had quickly become subjects of popular mythology. On the other, while the adventure-tale quality of Fidel Castro’s quest lay at the heart of this story of national self, the album also contained numerous features that would sit uncomfortably with dominant renditions of the Revolution’s emergence in years to come. Secondary and later overlooked anti-Batista movements received legitimizing coverage in its pages. Cuba’s traditional communist party—soon among the primary factions competing for revolutionary political power—was nowhere to be found. Most striking of all was the mixture of faces in the book’s concluding pantheon of heroes. As early as a few months after the album’s publication, several of the men pictured would begin falling afoul of the Revolution as it radicalized, finding themselves imprisoned or making their way to exile to conspire. One of the earliest, most familiar representations of the Revolution’s insurgent history, therefore, quickly became politically incorrect. Excised from official narratives thereafter, a handful of individuals in the book’s pages would see their contributions to Batista’s defeat discounted or denied.

Figure 1.1. Cover of Album de la Revolución Cubana, 1952–1959 (Havana: Revista Cinegráfico, S.A., 1959). Casanas Family Collection, Special Collections and University Archives, Florida International University Libraries, Miami, FL. Image reproduction courtesy of University of Florida Digital Collections and Digital Library of the Caribbean, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

The Album de la Revolución Cubana provides a useful entry point, if not metaphor, for this chapter’s central concerns. Scholars have long emphasized the extraordinary sense of historic messianism that attended Fidel Castro’s rise to power. For most Cubans, this revolution—Fidel’s revolution—represented the awaited moral realization not just of the anti-Batista struggle, but of the nation’s long-frustrated dreams.4 Still, if the Cuban Revolution came to power with its story already partially written, competing claims over revolutionary bona fides, and for the historical legitimacy to speak in the Revolution’s name, were still taking shape. While Cuba’s previously unsatisfied national aspirations finally seemed on the threshold of fulfillment, the anti-Batista front had been a moving target comprised of multiple, often-fractious organizations.5 Disparate groups embraced common hopes for national dignity and reform, but personality politics, past strategic rivalries, and ideological fractures within and between factions had the potential to drive them apart.

A close look, then, at rare press and other sources from the Revolution’s first eighteen months offers a contradictory, and until now underhistoricized, picture of memory mobilization alongside simmering retrospective quarrels. This chapter also reveals the ways the Cuban memory wars did not simply proceed along a predetermined, polarized path, but instead involved multiple political actors engaged in active, complex wars of position. Vast swaths of Cuban society became determined to purge the human and institutional ills of their nation’s past. Yet political scores also remained unsettled, and the depth of the economic problems in Cuba’s history requiring transformation, not to mention the best way to address them, remained a source of disagreement. Contending visions of the Revolution’s future thus quickly turned on not just differing understandings of the project’s social and political roots but also on various individuals’ and groups’ assertions of what they had or had not done in its service. As the rubber hit the road, arguments about the Revolution’s direction were intimately related to confrontations over legacies, compromises, and decisions made before its “triumph.” These battles persisted alongside unprecedented expressions of nationalist exuberance and faith.

Fidel Castro watched these disputes from a privileged position. As the unquestioned leader of revolutionary forces (even before having formally occupied a government post), his support or disapproval could take contending actors in and out of the political cold. At the same time, for most of 1959 Castro sought to appear above the fray, constructing an ostensibly nonsectarian narrative of Cuban history as deferred deliverance, one that naturally privileged his own movement’s leadership and encouraged Cubans to get on board or get out of the way. This does not mean, however, that his was the only relevant voice. This chapter thus decenters Fidel Castro’s words and appearances, covered so well by other historians, to foreground political actors and press outlets more commonly overlooked. By late 1959 and 1960, however, Castro’s insistence that anticommunism itself represented the historical blight that the Revolution most needed to exorcise would tilt the partisan memory balance in clear, influential ways.

Looking back, another dynamic stands out from these early counterpoints of retrospective argument and agitation—one that further complicates the work of interpreting their meaning. Namely, in the course of staking out their credentials, actors in and out of the new government said and wrote things that later they would find more convenient to forget. Whether Fidel Castro’s vague pledges to convene elections, or more moderate anti-Batista voices’ defense of early revolutionary tribunals (subsequently remembered by many as the first sign of the Revolution’s antidemocratic impulses), the domestic press overflowed with declarations that had the potential to embarrass once the ideological die were cast. The exercise in this chapter, then—like in this book as a whole—becomes double: to track the multiple origin stories and claims to historical standing that competed for credibility during the Revolution’s tumultuous first eighteen months or so, while also recovering some of the positions, players, and assertions that a more polarized climate beginning in 1960 would conspire to erase.

As Cuba’s domestic memory battles increasingly collided with the international politics of the Cold War, mounting bilateral tensions with Washington deflected Cubans’ retrospective fissures away from internal matters toward the longer legacies of U.S.-Cuban affairs. Rivalries for historical position along factional lines from the Revolution’s first stage took a back seat to an anti-imperialist dream. Thereafter, privileged narrators in the media and the emerging state would recast what had been a deeply conflicted process of political and economic transformation into a groundswell in favor of unitary change. In this new, radicalized scenario, which led to the declaration of the Revolution’s “socialist” character, ideological labels or a nuanced understanding of Cuba’s recent history mattered less than patriotic belief.

“Ahora sí …”: Historical Communion and Rupture

“This time, the Revolution is for real.” So proclaimed Fidel Castro upon his triumphal entrance into the city of Santiago de Cuba on January 1, 1959. Euphoria had already gripped the island’s streets as news spread the night before that Fulgencio Batista had fled. As the undisputed “maximum leader” of the Revolution’s words made clear, much more was at stake than a mere political turnover. “It will not be like in [the war of 18]95,” Castro declared,

when the Americans came and made themselves the owners of this place (Applause). … It will not be like in [19]33, when just as people began to believe that a revolution was being made, Mr. Batista came along and betrayed the revolution, taking over power and installing a dictatorship for eleven years. It will not be like in [19]44, the year in which the crowds got fired up, believing that finally the people were coming to power, when really those who came to power were thieves. Neither thieves, nor traitors, nor interventionists! This time, the Revolution is for real.6

No matter how often these lines have been quoted, the clarity and reach of the Revolution’s foundational myth continue to be extraordinary. As we saw in the introduction, Cuban politics had been haunted for decades by what felt to many like an “unfinished history.”7 Now, Cubans across the moderate-to-left side of the political spectrum—including some who later became Fidel Castro’s enemies—understood the movement’s victory as the consummation of a longer quest. “The [national] emancipation struggle,” wrote Mario Llerena, former chairman of the 26th of July Movement’s New York chapter and future anti-Castro exile, “can be conceived as a continuous process, moving toward one goal, as much as it seems to present itself in different chapters or eras.”8 “The Cuban Revolution,” agreed editors at the progressive but anticommunist Prensa Libre, “is one, only one, [and it] began at the dawn of the last century and it grew and perfected itself and took shape and authority and victory over the course of space and time, until arriving at our days.” These statements reflect the wide berth of the anti-Batista coalition at the start of 1959. Still, it is remarkable just how much the early prorevolutionary rhetoric of many who eventually found themselves in Fidel Castro’s crosshairs prefigured and echoed the words of the comandante (or commander, one of Castro’s many titles).9

After half a century of political turmoil, most Cubans were more eager than ever to end cycles of repeated disappointment to which they previously felt condemned. With respect to the politics of historical memory, however, such expectations presented the emergent political leadership with a thorny challenge. On the one hand, new officials needed to position their government as the continuation and outgrowth of nationalist struggles that had come before it. On the other, spokespeople for the nation’s new political project also had to differentiate their course, making clear that past mistakes would not be repeated. The first months of the Cuban Revolution in power thus bore witness to ubiquitous displays of historical communion and exorcism—ceremonies headline-grabbing and mundane, all to “render the revolution as vindication of the past and the past as validation of the revolution,” as the historian Louis A. Pérez Jr. has written evocatively.10

Perhaps more skepticism was warranted. Morality, or the pursuit of moral redemption—not Marxism—had long functioned as the dominant idiom of Cuban political life. It was in this spirit that many believed the time had finally come to break with what sociologist Nelson P. Valdés later called the “identical,” tragic “script” of disillusionment—regardless of ideology—that had tended to repeat itself in island affairs to that point.11 Yet what historian María del Pilar Díaz Castañón has labeled the ahora sí or “now, finally” impulse in Cuban political psychology—the idea, or hope, that Cuba’s moment had arrived once and for all—already had an “ancient” and clearly discouraging track record in the island’s history.12 After failing in his first attempt to start an anti-Batista insurrection at the Moncada Barracks of Santiago de Cuba in 1953, Fidel Castro confidently declared, “La historia me absolverá” (“History will absolve me”) at his subsequent trial.13 But, as writer Virgilio Piñera wondered “in silence” just two weeks after the rebel victory six years later, “This time now, will it be like other times past?”14 Cuba’s “myth of subjunctive possibility” cried out to finally come to fruition, but reality could once again disappoint.15

For most of 1959, those holding such doubts were few and far between. Popular mobilizations and rallies across the island, starting with Fidel Castro’s seven-day “Caravan of Liberty” from Santiago to Havana, coalesced a sense of national optimism as never before. Photographs of the spontaneous celebrations greeting his and other rebels’ arrivals in town after town—taken by unofficial and soon quasi-official photographers of the Revolution alike—quickly spread across the pages of the press, becoming iconic parts of an emergent collective visual memory of the Revolution in their own right.16 “When a people learns and knows,” wrote a Dr. Pascual B. Marcos Vegueri that September, echoing the sentiments of the majority, “all that the Cuban people have learned and know … conscious of and justly enthralled with its destiny … that people rejects with intelligence, energy, and courage, any pretension of regressing to its iniquitous, miserable, and despicable past.”17 The uniqueness of this moment in Cuba’s history for most seeme...