eBook - ePub

Designing the Search Experience

The Information Architecture of Discovery

Tony Russell-Rose,Tyler Tate

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 320 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Designing the Search Experience

The Information Architecture of Discovery

Tony Russell-Rose,Tyler Tate

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Search is not just a box and ten blue links. Search is a journey: an exploration where what we encounter along the way changes what we seek. But in order to guide people along this journey, designers must understand both the art and science of search.In Designing the Search Experience, authors Tony Russell-Rose and Tyler Tate weave together the theories of information seeking with the practice of user interface design.

- Understand how people search, and how the concepts of information seeking, information foraging, and sensemaking underpin the search process

- Apply the principles of user-centered design to the search box, search results, faceted navigation, mobile interfaces, social search, and much more

- Design the cross-channel search experiences of tomorrow that span desktop, tablet, mobile, and other devices

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Designing the Search Experience als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Designing the Search Experience von Tony Russell-Rose,Tyler Tate im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Design & UI/UX Design. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Thema

DesignThema

UI/UX DesignPart 1. A Framework for Search and Discovery

“This is a huge change to the overall user experience. It transforms the way we think and opens opportunities to use search in a disruptive fashion. I love it!”

“Personally, I think people will get annoyed with it. The interface itself isn’t anything new, and it’s an outdated concept. When you think about state-of-the-art search, it should be less about searching and more about finding.”

“I’m excited to see how this will affect our searching habits. It has proven to be very useful and intuitive in my research work. In fact, it has also opened perspectives that I would otherwise have missed. Fantastic!”

“I can’t stand it—it’s a hindrance, not an aid. It slows me down. It is an unnecessary feature that has ruined the interface. I am so annoyed that I have to manually turn this nonsense off.”

These are a few of the views that were expressed when Google introduced instant search results that dynamically update as the user types into the search box (Figure P1.1). It’s a simple concept, but one that polarized opinion—some declared that it would revolutionize the way we search; others saw it as a mere distraction.

Figure P1.1 Instant search results from Google.

The same debate could apply to almost any aspect of the search experience. Different people have different views, so conflict is inevitable. Design is a matter of opinion, and there is no “right answer.” Right?

Although it’s difficult to rule out subjectivity entirely, there are productive ways we can move such a debate forward. The most fundamental step is to recognize that the opinions are themselves based on a set of assumptions—in particular, assumptions about who is doing the searching, what they are trying to achieve and under what circumstances, and how they are going about it. Each of these assumptions corresponds to a separate dimension by which we can define the search experience.

The Dimensions of Search User Experience

The first of these dimensions is the type of user, in particular his or her level of knowledge and expertise. For example, consider the users of an online retail store: are they knowledgeable enthusiasts or novice shoppers? Likewise, for an electronic component supplier: are the users expert engineers or purchasing agents with limited domain knowledge?

Once we understand the user, we can move on to the second dimension: his or her goal. This goal can vary from simple fact checking to more complex explorations and analyses. For example, are users searching for a specific item such as the latest Harry Potter book? Or are they looking to choose from a broader range of possibilities, such as finding shoes to match a business suit? Or are they unsure of what they are looking for in the first place, knowing only that they would like to find a suitable gift?

Knowing the users and their goals, we can now consider the third dimension: the context. Context includes a range of influences, from the physical to the intangible. For example, is the user at the workplace, where the task and the organizational setting dominate? Or is the user at home, where social context might become more important? Perhaps he or she is using a mobile device while travelling, during which physical context shapes the search experience.

Finally, based on our understanding of the users, their task and the wider context, we can consider the fourth dimension: their search mode. Search isn’t just about finding things—on the contrary, most finding tasks are but a small part of a much larger overall task. Consequently, our focus must be on understanding the complete task life cycle and helping users complete their overall information goals. This includes activities such as comparing, exploring, evaluating, analyzing, and much more.

So returning to the opening exchange, we can now see the debate in a different light: to understand those differences in opinion, we need to recognize the underlying assumptions. Likewise, to understand human information seeking behavior, we need a framework by which it can be defined: the users, their goals, the context, and search modes. In the following four chapters, we examine each of these dimensions and explore how to apply them in designing the search experience.

Chapter 1

The User

“Man is a being in search of meaning.”

— Plato

We begin where every discussion of design should: with the user. Although the entire book is about crafting user-centered search solutions, Chapter 1 homes in on the human mind itself. We want to know what makes people tick. What are the cognitive processes that govern how information is perceived, stored, and retrieved? What are the individual differences between how people learn, analyze information, and approach problems? By applying insights from cognitive psychology, we’ll be able to better understand how users approach the tricky problem that is search.

The rest of Part 1 deals with situated users: their goals (Chapter 2), context (Chapter 3), and modes of interaction (Chapter 4). Here, however, we look at users in isolation and focus on their intrinsic characteristics. We begin by looking at behavioral differences between novices and experts, continue by contrasting cognitive styles, and end by considering modes of learning.

Novices and Experts

Are you more comfortable taking a photograph using your mobile phone, a point-and-shoot camera, or an SLR brimming with buttons and dials? How you answer that question is probably a good indicator of your photographic expertise. If you primarily take quick, off-the-cuff snapshots, your phone or point-and-shoot camera will probably suffice. If you’re a professional photographer (or a serious amateur), on the other hand, you probably prefer using an SLR that gives you full control over the focus, aperture, exposure, and other variables of the image. In other words, both novices and experts gravitate toward the tools that best match their abilities.

Expertise plays a significant role in how people seek information. Understanding the differences between novices and experts will enable us to design better search experiences for everyone. But first, it’s worth distinguishing between two dimensions of expertise.

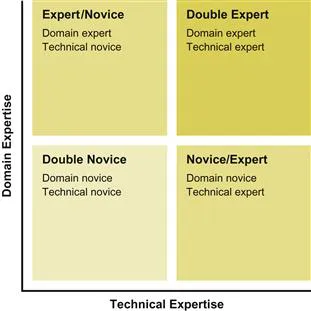

Domain expertise versus technical expertise

Expertise is frequently lumped into a single category, but there are in fact two types of expertise that affect information seeking: domain and technical expertise. Domain expertise defines one’s familiarity with a given subject matter; a professional photographer, for instance, has substantial domain expertise in the field of photography. Technical expertise, on the other hand, indicates one’s proficiency at using computers, the Internet, search engines, and the like.

Each dimension of expertise is valuable, but users are most likely to succeed when both are present. Jenkins et al. (2003) observed that domain novices have difficulty discerning the relevance of information or the reliability of its source, whereas domain experts make these judgments much more naturally. They also found that technical novices tend to practice a breadth-first strategy to information seeking that helps them avoid the disorientation caused by venturing too far away from the their starting point. Technical experts, on the other hand, apply a depth-first approach by following a number of links deeper into the information space. In other words, novices orienteer by slowly scouting out the territory (O’Day and Jeffries, 1993), and experts teleport, quickly jumping to their destination (Teevan et al., 2004).

In combination, the domain and technical dimensions of expertise describe four types of users (Figure 1.1):

• Double experts

• Domain expert/technical novices

• Domain novice/technical experts

• Double novices

Figure 1.1 Two dimensions of expertise: domain and technical.

Double novices orienteer

The discipline of orienteering originated in the Swedish military in the 1800s and is now a sport practiced throughout Scandinavia. Equipped with a map and compass, participants navigate between control points spread over miles of unfamiliar terrain as they strive to complete the course. But the journey is anything but direct. If an orienteerer loses his bearings along the way, heading back to the previous control point may be the only option to avoid becoming lost in the wilderness.

The information seeking of novices shares similarities with the practice of orienteering. Although both domain and technical novices face resistance along the way, the ...