![]()

1

Dionysus

Dionysus is the largest role in Aristophanes’ Frogs, and the character appears in almost every scene. Dionysus was a god of exuberance and community building, and these qualities are evident in his responsibility for both wine and theatre. From theatre, however, come impersonation and masks; and from wine comes responsibility for madness and departure from one’s self. His rituals could emphasize fertility and vegetation. The worship of Dionysus in Athens recognized all of these aspects and more, and it is a mistake to try to contain the god within too narrow a compass.1 At the same time, as Albert Henrichs has argued, ‘No other Greek god has created more confusion in the modern mind, nor produced a wider spectrum of different and often contradictory interpretation.’2 Multiple conflicting stories exist about the god’s double- or triple-birth, and his death and restoration: Dionysian exuberance embraces life beyond death, and some rituals focus on a happy afterlife for his believers. His name is found on Bronze Age Linear B tablets from c. 1250 BCE. In the earliest Greek literature, he is ‘a joy for mortals’ (Homer, Iliad 14.325) who is nevertheless already associated with death (Odyssey 11.325 and 24.74); as Heraclitus observed, ‘Hades and Dionysus are the same’ (fr. 15 DK).

Traditionally, Dionysus was first recognized as a god and worshipped in Attica – the area controlled by the polis (city) Athens – in the community (deme) of Ikarion. He taught viticulture to the Athenian Icarius, and he avenged the hero’s death when he was killed by drunken shepherds. Ikarion was also supposedly the deme of Thespis, the legendary inventor of tragedy. Dionysus was worshipped annually in a local festival organized by the deme, and the celebration included productions of tragedies. Not every Rural Dionysia included theatrical performances, but many did, and there are indications of theatrical performances in twenty-three demes and the area of Brauron in the classical period, though not all were in existence in the late fifth century.3 In an early comedy of Aristophanes (Acharnians 237–79, dated 425 BCE) a character performs a procession (pompē) and song that was recognizable enough to evoke among spectators the procession, accompanied by a phallic song, from a Rural Dionysia.4 These processions, with an oversized phallus-pole, imagined satyrs as attendants of Dionysus. The Roman writer Pausanias describes a painted version of the myth in Athens (1.20.3), which provides a model for these processions.5

In the Attic festival calendar, the Rural Dionysia begins a season of Dionysus worship that extends through the winter, as ‘Rural Dionysia, Lenaia, Anthesteria, and City Dionysia succeed one another at intervals of roughly a month over the period from about December to March’.6 In different ways, all of these festivals are relevant to the study of Frogs. The Lenaia and the City Dionysia will be discussed later [2], as will Dionysus’ connection to the Eleusinian Mysteries [12], but the Anthesteria, which the historian Thucydides calls the ‘older Dionysia’ (2.15.4), is also relevant: ‘It is a festival at which some social norms are overturned–slaves dine with their masters, young men insult their betters from wagons – and even (so to speak) some cosmic norms: the dead roam the streets, a god visits the city (arriving from the sea?) to take a mortal bride.’7 The festival lasted three days, each of which is associated with a particular clay vessel: Pithoigia, Choes and Chytroi. It was celebrated at the Limnaion, an old (unidentified) temple of Dionysus ‘in the marshes’. Pithoigia celebrated opening large jars (pithoi) of wine; Choes poured wine from pitchers (choes) and featured a drinking contest, in which silence commemorated Athens receiving the polluted Orestes into its community, and concluded with libations for the dead; Chytroi continued the association with the dead as porridge was made in pots (chytroi) offered to Hermes.

This description sidesteps the life of Dionysus, his birth and youthful adventures, his rescue of Ariadne after she is abandoned on Naxos by Theseus, his defeat of pirates by metamorphosing them into dolphins, his arrival from the East and reception in Greece, among many other stories, because from the perspective of Frogs, very little of that matters. While Euripides’ Bacchae can offer a sophistic debate about the nature of his birth (Bacch. 286–97), ‘the Dionysos of Frogs has little or nothing to do with representations of the god in fifth-century sculpture or vase painting, and by his dress alone he would have been recognized as a figure quite distinct from the mythic or cultic manifestations of the god.’8 Aristophanes’ Dionysus drinks no wine, does not carry the thyrsus (a fennel staff wrapped with ivy with which Dionysus is associated) and is not attended by dancing maenads or satyrs.9

Even his visual appearance in Frogs is uncertain. Until the fifth century, Dionysus is always represented with a dark beard. Vase fragments from the 470s begin to show a beardless Dionysus, which may be influenced by a notable theatrical presentation of the god: Aeschylus’ lost play Edonians, where Dionysus is presented as womanish (fr. 61), is one possible source for this influence.10 Whatever the case, this was the image the sculptor Pheidias displayed on the east pediment of the Parthenon in the 430s, and subsequent artists could feel free to use either appearance.11 In Euripides’ Bacchae (left unproduced at the author’s death in 406, and possibly presented a few months after Frogs), Dionysus appears disguised as a mortal but is young and unbearded.12 While the Dionysus of cult presented a mature god with dark hair and beard, the Dionysus of myth, as seen in tragedy and satyr play that often focused on his youthful adventures, presented a young man. Both of these possibilities were available to a comic poet presenting Dionysus onstage in the late fifth century.

Dionysus had appeared on the comic stage before Frogs, for example in Dionysalexandros (‘Dionysus-becomes-Paris’/’Dionys-is-Alexander’) by Cratinus, whose theatrical career flourished c. 454–423. The play was produced in 430, 429 or perhaps 437.13 A plot summary preserved on papyrus (the ‘hypothesis’, POxy 663) allows us to say much about this play. Dionysus appears to disguise himself as the shepherd Paris (= Alexander), in order to judge the beauty contest between goddesses that will lead to the Trojan War. The chorus of satyrs tease Dionysus as he appears, perhaps because his beard is shaved and he is dressed as a shepherd:

After this he sails off to Sparta, takes Helen away, and returns to Ida. But he hears a little while later that the Greeks are ravaging the countryside <and looking for> Alexander. He hides Helen very quickly in a basket and changing himself into a ram awaits developments. Alexander appears and detects each of them, and orders them to be taken to the ship, meaning to give them back to the Greeks. When Helen refuses, he takes pity on her and holds on to her, to keep her as his wife. Dionysus he sends off to be handed over. The satyrs go along with him, encouraging him and insisting that they will not betray him.

POxy 663, lines 20–4414

Many questions remain unanswered, but the spectacle offered by the play is obvious: Dionysus, perhaps shaved to become Paris (fr. 48, ‘I appeared shorn, like a fleece’; cf. Thesmophoriazusae 215–48), is somehow also transformed into a ram (fr. 45, ‘And the silly fool just walks about going “baa baa” ’); Helen, perhaps used to finer living (fr. 42, ‘Do you [sing.] want gateposts and fancy porches?’), is indecorously hidden in a basket, allowing a jack-in-the-box appearance when the real Alexander arrives. Dionysalexandros also involved political satire: ‘In the play Pericles is very persuasively made fun of through innuendo [di’ emphaseōs] for having brought the war on the Athenians’ (POxy 663, lines 44–8). Exactly what emphasis means is debated, but somehow the appearance of Dionysus or Alexander evoked the general Pericles, without making the connection explicit.15 Whatever his exact appearance, somewhere in the play Dionysus was described with his usual iconographic attributes (fr.40.2: ‘<He had> a thyrsus, saffron robe [krokotos] with lots of decoration, large drinking cup’).16

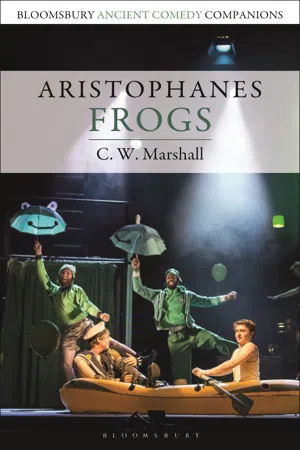

There were, then, many Dionysus comedies.17 Relevant to Frogs, Aristophanes wrote Babylonians for production at the City Dionysia of 426 [3], in which Dionysus was also a character (fr. 75) and may have been presented as an inept rower, who must learn aspects of seafaring.18 Dionysus rowing an onstage ship, perhaps assisted by the chorus of Babylonians, again suggests a moment of theatrical spectacle. Indeed, a scene with Dionysus at the oar recurred, in Eupolis’ Taxiarchs and Aristophanes’ Frogs, with rowing scenes also attested in plays by Hermippus and Cratinus [9].19 These plays engage with the Dionysus of ritual and of myth, yet they are similarly free to do with him whatever is needed by the plot.

![]()

2

Lenaia

The two principal theatrical festivals in Athens were the Lenaia and the City Dionysia. The City Dionysia was celebrated in the sanctuary of Dionysus Eleuthereus on the south slope of the Acropolis, where the theatre can still be seen today. The cult title Eleuthereus evokes ‘freedom’ from responsibilities, the ‘bounty’ of the god and the ‘liberty’ from tyranny that Athens enjoyed after the democracy was established in 508/507, but it was explicitly tied to the town Eleutherai, which bordered Boeotia and came under Athenian control around this time.1 The cult image of the god was taken to the town, and was returned in a torchlight procession (pompē) and celebration that evening. The next day, a proagōn (‘pre-contest’) ceremony announced the competitive events that would follow, and perhaps offered a preview of what was to come. After the mid-440s, this occurred in the Odeion, a large roofed building immediately next to the theatre. Another procession led to the theatre, where pre-play ceremonies might display the richness of Athens and its political control over the ...