![]()

1 A Career of Despair

Angst essen Seele auf/Fear Eats the Soul (1973) won the German Film Prize and Fassbinder himself listed it in his own Top Ten. The director’s then current boyfriend, El Hedi ben Salem m’Barek Mohammad Mustafa, stars as Ali, a guest worker from Morocco who marries a widowed cleaning woman thirty years his senior. Their cross-generational, cross-cultural and mixed-race love affair is met with ridicule and consistent acts of cruelty from nearly everyone around them. A portrait of prejudice and pettiness in everyday postwar Germany, Fear Eats the Soul is, despite an abundance of awful wretchedness, perhaps Fassbinder’s most tender and optimistic work.

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

From 1966 until his early death in 1982 at the age of thirty-seven, Rainer Werner Fassbinder made over forty films. The years of his output roughly coincide with the halcyon years of rock and roll, which were, not coincidentally, years of intense political and personal rebellion in Germany and elsewhere. Like the primary innovators in rock music who generally lacked professional training in voice or guitar, Fassbinder was himself a self-taught film-maker. His films wrestle with the medium of film-making, with the act of cultural representation itself and with the authority invested in all conventions – including those of cinema – and suggest that art must change life to make life more livable. ‘At some point’, Fassbinder insisted during a 1974 conversation about Fear Eats the Soul, ‘films have to stop being films.’1

In his brief, excessively prolific career, Fassbinder worked in a range of genres, often combining more than one together in a single film, including gangster, satire, crime, noir, autobiography, pseudo-Western, television soap opera, social criticism, Brechtian ethnography, literary classic, science fiction, documentary and melodrama. Emotional violence, shame, self-pity and regret permeate Fassbinder’s films and were inter-twined in the roller-coaster of euphoria and angst that was his life. As noted Fassbinder historian Thomas Elsaesser exclaims: ‘Here, surely, is a director who practiced an unparalleled symbiosis between living and filming, loving and hating, working and dying.’2 In Fassbinder: The Life and Work of a Provocative Genius, Christian Braad Thomsen introduces him like this:

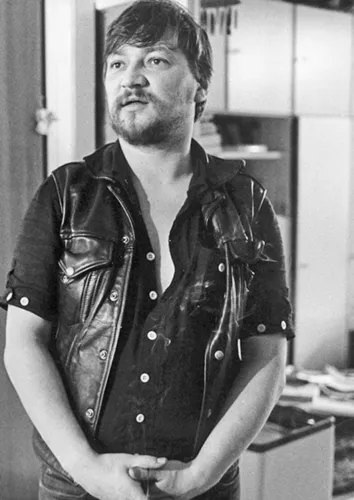

He was gentle and brutal, tender and cynical, self-sacrificing and egocentric; he was ruthlessly dictatorial and yet always dreamed of working in groups and collectives. He was obese, unkempt, slovenly, went around in a leather jerkin and looked like a boozer in the bar on the corner. But when he worked with the camera and actors, he had the grace and vitality of a ballet dancer. The ugly frog turned into a handsome prince when he was kissed, not by a princess, but by the film camera, which in an early film Fassbinder described as a ‘holy whore’.3

Fassbinder insisted that he made films ‘for personal reasons only’. Certainly no major film-maker has ever worked as closely, crudely or honestly with the personal histories of his actors and himself. ‘Few directors’, asserts one of his American interpreters, ‘insinuate their own lives into their films with as much passionate intensity.’4

This is not to say that his films are autobiographical in the way that a memoir or a documentary attempts to be. All artists, but especially those working within a narrative tradition, necessarily draw on life experience. Fassbinder’s particular distinction is the depth, temporal and political, embedded in his characters and situations. He understood that history is written into our very bodies, that events of the past have determined not only our names, the colour of our skin, the way we dress and speak, whom we love and marry, but also the way we feel – even in our most innermost thoughts. History, language, custom, culture, politics, economics, memory: these are the prison houses his work tries to unlock. Dealing directly with the history and situation of his own Germany, his films address the personal and political problems faced by all of us who live in highly industrialised societies built on exploitation, imperialism and nationalism. Because of his unique contributions to film-making, his work remains rich in suggestion and demonstration for those of us concerned with the future of film and art.

Like Bertolt Brecht, Fassbinder utilized different theatrical conventions and cinematic ploys to encourage his audience to think. His comments on Effi Briest (1972–4), the film he worked on while simultaneously making Fear Eats the Soul, provide some insight into his thoughts at that time:

It is an attempt to make a film entirely for the head, a film, that is, in which one doesn’t give up thinking but instead begins to think, and just as in reading one really makes sense of letters and sentences only through imagination, so it should also happen in this film. Thus everyone should have the possibility and the freedom to make this film his own, as he sees it.5

His creative energies were continually drawn toward themes of entrapment, including the claustrophobia of marriage and family life, the oppressive labour conditions of workers, the inherent distrust between petty criminals and the hypocritical conventions of middle-class living. Commentaries on Fassbinder, especially those circulated in his native West Germany during his lifetime, ‘make frequent reference to the director’s unhappy childhood and parents’ divorce, as if the social and emotional disarray of his individual youth sufficiently explains a pessimistic view of society, marriage and the family.

Fassbinder was born in Germany in 1945, less than a month after World War II ended. Postwar West Germany maintained many of the ideological components that had been central to Nazi philosophy: suspicion of foreigners, contempt for non-Aryan people, subordination of women, the criminalization of homosexuals. Nazi ideals and Nazi supporters necessarily inhabited the Germany of Fassbinder’s youth: hardly anyone else was left. The Jews, intellectuals, Communists and other dissidents had all been slaughtered or exiled. Some of the same officials served under both Hitler and his successors. The narrowly elected first Federal Chancellor of West Germany, Konrad Adenauer, had been forced into exile during the war for trying to resist Hitler. Postwar, as Federal Chancellor during the Wirtschaftswunder or ‘economic miracle’ of 1949–63, Adenauer faced the daunting task of rebuilding and reconciling an economically and otherwise destroyed Germany. Or, rather, ‘half’ of Germany. East Germany was itself a material and symbolic manifestation of the suicide Germany committed in World War II: the nation literally cut itself in two. Fassbinder’s expansive filmography includes historical works, such as his international success, The Marriage of Maria Braun (1978), which consider Germany’s immediate postwar years, along with films, including the epic, Berlin Alexanderplatz (1979–80), set during the rise of National Socialism. Fassbinder himself was dead before the unification of East and West Germany in 1989.

In Fear Eats the Soul, the film’s heroine, Emmi Kurowski (Brigitte Mira), acknowledges she was a member of Hitler’s party as casually as if admitting to being a baptized Catholic, a practizing Lutheran or a Saturday-evening pinochle player. Fassbinder’s films not only dare to attest to the widespread support the Third Reich received from the general population but also, more importantly, continuously reiterate that fascism is not simply a governmental problem but a psychic corruption that begins at home, in marriage, in the family, in the self. Like so many other social critics, Fassbinder was not often able to control the horrible things he recognized around him or in himself. It is a testament to his artistic honesty that he frequently cast himself, as he does for his appearance as Emmi’s son-in-law in Fear Eats the Soul, as a swinish, barbaric, sadistic man. Though the legacy of the Third Reich fuelled his political and creative imagination – and set the historical stage for his own life drama – he identified the root prejudices of Nazi ideology as aspects of European culture that predated and outlasted Hitler’s Germany.

Fassbinder as Emmi’s son-in-law Eugen in Fear Eats the Soul

The standard narrative structure in a Fassbinder film is that it opens in the middle of a problem and, as the film progresses, the problem gives rise to further difficulties. ‘Repetition, variation and reversal – that is the pattern of Fassbinder’s closed melodramas,’ observes James Roy MacBean. ‘But the reversal is not reversal of fortune; no, on the contrary, it’s a redoubling of misfortunes, a compounding of the woes of life, which by the end of the film have come to press in from new, unexpected quarters as well as from their old sources.’6 The vice-like grip Fassbinder’s films exert on the viewer, the psychological and political tightening of so many harsh and often unpredictable screws, not only alienated Fassbinder from the entertainment-seeking members of his first-run audiences but also greatly dismayed – even outraged – politically progressive viewers during the 1970s who had reason to hope that Fassbinder would provide new and affirmative characterizations of the emerging civil rights, gay rights and feminist mobilizations. One critic attacked Fox and His Friends (1974), Fassbinder’s only outwardly homosexual film, claiming its ‘version of homosexuality degrades us all and should be roundly denounced’.7 Similarly appalled by the ‘freak show’ aspect of The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972), critic Caroline Sheldon concluded that Fassbinder and ‘other gay film-makers are no more sympathetic to lesbians than straight ones’.8 But Fassbinder never affirms. The political value of his work exists, as Richard Dyer first suggested, in ‘the way the films can be taken up, used, made to do political work through discussion, critical debate and so on’.9

The standard pattern of negative escalation that accompanies Fassbinder’s plots takes its toll on his lead characters, who usually find themselves dead, in hospital or otherwise wrecked by the end of a film. A stiff silence of existential desperation creates a continuous tension in his films, technically communicated in his tendency to allow the camera to remain fixed on a troubled face or strained group. Frequently his films not only end unhappily but without any resolution at all, as if Fassbinder, in a desperate attempt to reveal the suppressed aspects of human social dynamics, is himself left groping. His unique insight was that politics, economics and prejudice divide human beings so far from each other that we can never be whole. It could be said that all of his work is about hypocrisy. Or perfidy. Or self-deception. In response to the routine charges of ‘pessimism’ lobbed against him, he countered with:

I don’t see my films like that. They developed out of the position that the revolution should take place not on the screen, but in life itself, and when I show things going wrong, I do it to make people aware that this is what happens unless they change their lives. If, in a film that ends pessimistically, it’s possible to make clear to people why it happens like that, then the effect of the film is not finally pessimistic.10

The rapidity with which Fassbinder worked – ‘This guy turns out movies like other people roll cigarettes,’ they used to say – guaranteed that at least some of his work would be sloppy – and it is. But his best films, including Fear Eats the Soul, Fox and His Friends, The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, In a Year of Thirteen Moons, The Third Generation, Fontane: Effi Briest, Mother Küsters Goes to Heaven, The Merchant of Four Seasons, Beware of a Holy Whore, The Marriage of Maria Braun, Berlin Alexanderplatz and Fear of Fear, succeed remarkably. His prescience was such that more than a few of the themes he explored that were considered idiosyncratic or of fleeting, sensational-only interest when they were made in the 1970s have subsequently emerged as crucial social and political issues in the twenty-first century. These include the Gastarbeiter theme in Fear Eats the Soul; the male-to-female gender reassignment in In a Year of Thirteen Moons (1978); the complications of gay male love in Fox and His Friends; the chemical tranquillization of the housewife in Fear of Fear (1975); and the suggestion, in The Third Generation (1979), that contemporary governments might manufacture terrorism to support their own political agendas.

Fassbinder’s mother, Lilo Pempeit (on the right), as a busybody in Fear Eats the Soul

Fassbinder’s capacity for social prophe...