eBook - ePub

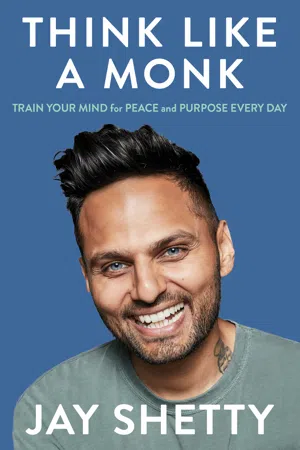

Think Like a Monk

Train Your Mind for Peace and Purpose Every Day

Jay Shetty

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Think Like a Monk

Train Your Mind for Peace and Purpose Every Day

Jay Shetty

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Jay Shetty, social media superstar and host of the #1 podcast ‘On Purpose’, distils the timeless wisdom he learned as a practising monk into practical steps anyone can take every day to live a less anxious, more meaningful life.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Think Like a Monk als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Think Like a Monk von Jay Shetty im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Teologia e religione & Buddismo. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Thema

Teologia e religioneThema

BuddismoPART ONE

LET GO

ONE

IDENTITY

I Am What I Think I Am

It is better to live your own destiny imperfectly than to live an imitation of somebody else’s life with perfection.

—Bhagavad Gita 3.35

In 1902, the sociologist Charles Horton Cooley wrote: “I am not what I think I am, and I am not what you think I am. I am what I think you think I am.”

Let that blow your mind for a moment.

Our identity is wrapped up in what others think of us—or, more accurately, what we think others think of us.

Not only is our self-image tied up in how we think others see us, but most of our efforts at self-improvement are really just us trying to meet that imagined ideal. If we think someone we admire sees wealth as success, then we chase wealth to impress that person. If we imagine that a friend is judging our looks, we tailor our appearance in response. In West Side Story, Maria meets a boy who’s into her. What’s her very next song? “I Feel Pretty.”

As of this writing, the world’s only triple Best Actor Oscar winner, Daniel Day-Lewis, has acted in just six films since 1998. He prepares for each role extensively, immersing himself completely in his character. For the role of Bill the Butcher in Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York, he trained as a butcher, spoke with a thick Irish accent on and off the set, and hired circus performers to teach him how to throw knives. And that’s only the beginning. He wore only authentic nineteenth-century clothing and walked around Rome in character, starting arguments and fights with strangers. Perhaps thanks to that clothing, he caught pneumonia.

Day-Lewis was employing a technique called method acting, which requires the actor to live as much like his character as possible in order to become the role he’s playing. This is an incredible skill and art, but often method actors become so absorbed in their character that the role takes on a life beyond the stage or screen. “I will admit that I went mad, totally mad,” Day-Lewis said to the Independent years later, admitting the role was “not so good for my physical or mental health.”

Unconsciously, we’re all method acting to some degree. We have personas we play online, at work, with friends, and at home. These different personas have their benefits. They enable us to make the money that pays our bills, they help us function in a workplace where we don’t always feel comfortable, they let us maintain relationships with people we don’t really like but need to interact with. But often our identity has so many layers that we lose sight of the real us, if we ever knew who or what that was in the first place. We bring our work role home with us, and we take the role we play with our friends into our romantic life, without any conscious control or intention. However successfully we play our roles, we end up feeling dissatisfied, depressed, unworthy, and unhappy. The “I” and “me,” small and vulnerable to begin with, get distorted.

We try to live up to what we think others think of us, even at the expense of our values.

Rarely, if ever, do we consciously, intentionally, create our own values. We make life choices using this twice-reflected image of who we might be, without really thinking it through. Cooley called this phenomenon the “Looking-Glass Self.”

We live in a perception of a perception of ourselves, and we’ve lost our real selves as a result. How can we recognize who we are and what makes us happy when we’re chasing the distorted reflection of someone else’s dreams?

You might think that the hard part about becoming a monk is letting go of the fun stuff: partying, sex, watching TV, owning things, sleeping in an actual bed (okay, the bed part was pretty rough). But before I took that step there was a bigger hurdle I had to overcome: breaking my “career” choice to my parents.

By the time I was wrapping up my final year of college, I had decided what path I wanted to take. I told my parents I would be turning down the job offers that had come my way. I always joke that as far as my parents were concerned, I had three career options: doctor, lawyer, or failure. There’s no better way to tell your parents that everything they did for you was a waste than to become a monk.

Like all parents, mine had dreams for me, but at least I had eased them into the idea that I might become a monk: Every year since I was eighteen I’d spent part of the summer interning at a finance job in London and part of the year training at the ashram in Mumbai. By the time I made my decision, my mother’s first concern was the same as any mother’s: my well-being. Would I have health care? Was “seeking enlightenment” just a fancy way of saying “sitting around all day”?

Even more challenging for my mother was that we were surrounded by friends and family who shared the doctor-lawyer-failure definition of success. Word spread that I was making this radical move, and her friends started saying “But you’ve invested so much in his education” and “He’s been brainwashed” and “He’s going to waste his life.” My friends too thought I was failing at life. I heard “You’re never going to get a job again” and “You’re throwing away any hope of earning a living.”

When you try to live your most authentic life, some of your relationships will be put in jeopardy. Losing them is a risk worth bearing; finding a way to keep them in your life is a challenge worth taking on.

Luckily, to my developing monk mind, the voices of my parents and their friends were not the most important guidelines I used when making this decision. Instead I relied on my own experience. Every year since I was eighteen I had tested both lives. I didn’t come home from my summer finance jobs feeling anything but hungry for dinner. But every time I left the ashram I thought, That was amazing. I just had the best time of my life. Experimenting with these widely diverse experiences, values, and belief systems helped me understand my own.

The reactions to my choice to become a monk are examples of the external pressures we all face throughout our lives. Our families, our friends, society, media—we are surrounded by images and voices telling us who we should be and what we should do.

They clamor with opinions and expectations and obligations. Go straight from high school to the best college, find a lucrative job, get married, buy a home, have children, get promoted. Cultural norms exist for a reason—there is nothing wrong with a society that offers models of what a fulfilling life might look like. But if we take on these goals without reflection, we’ll never understand why we don’t own a home or we’re not happy where we live, why our job feels hollow, whether we even want a spouse or any of the goals we’re striving for.

My decision to join the ashram turned up the volume of opinions and concerns around me, but, conveniently, my experiences in the ashram had also given me the tools I needed to filter out that noise. The cause and the solution were the same. I was less vulnerable to the noises around me, telling me what was normal, safe, practical, best. I didn’t shut out the people who loved me—I cared about them and didn’t want them to worry—but neither did I let their definitions of success and happiness dictate my choices. It was—at the time—the hardest decision I’d ever made, and it was the right one.

The voices of parents, friends, education, and media all crowd a young person’s mind, seeding beliefs and values. Society’s definition of a happy life is everybody’s and nobody’s. The only way to build a meaningful life is to filter out that noise and look within. This is the first step to building your monk mind.

We will start this journey the way monks do, by clearing away distractions. First, we’ll look at the external forces that shape us and distract us from our values. Then we will take stock of the values that currently shape our lives and reflect on whether they’re in line with who we want to be and how we want to live.

IS THIS DUST OR IS IT ME?

Gauranga Das offered me a beautiful metaphor to illustrate the external influences that obscure our true selves.

We are in a storeroom, lined with unused books and boxes full of artifacts. Unlike the rest of the ashram, which is always tidy and well swept, this place is dusty and draped in cobwebs. The senior monk leads me up to a mirror and says, “What can you see?”

Through the thick layer of dust, I can’t even see my reflection. I say as much, and the monk nods. Then he wipes the arm of his robe across the glass. A cloud of dust puffs into my face, stinging my eyes and filling my throat.

He says, “Your identity is a mirror covered with dust. When you first look in the mirror, the truth of who you are and what you value is obscured. Clearing it may not be pleasant, but only when that dust is gone can you see your true reflection.”

This was a practical demonstration of the words of Chaitanya, a sixteenth-century Bengali Hindu saint. Chaitanya called this state of affairs ceto-darpaṇa-mārjanam, or clearance of the impure mirror of the mind.

The foundation of virtually all monastic traditions is removing distractions that prevent us from focusing on what matters most—finding meaning in life by mastering physical and mental desires. Some traditions give up speaking, some give up sex, some give up worldly possessions, and some give up all three. In the ashram, we lived with just what we needed and nothing more. I experienced firsthand the enlightenment of letting go. When we are buried in nonessentials, we lose track of what is truly significant. I’m not asking you to give up any of these things, but I want to help you recognize and filter out the noise of external influences. This is how we clear the dust and see if those values truly reflect you.

Guiding values are the principles that are most important to us and that we feel should guide us: who we want to be, how we treat ourselves and others. Values tend to be single-word concepts like freedom, equality, compassion, honesty. That might sound rather abstract and idealistic, but values are really practical. They’re a kind of ethical GPS we can use to navigate through life. If you know your values, you have directions that point you toward the people and actions and habits that are best for you. Just as when we drive through a new area, we wander aimlessly without values; we take wrong turns, we get lost, we’re trapped by indecision. Values make it easier for you to surround yourself with the right people, make tough career choices, use your time more wisely, and focus your attention where it matters. Without them we are swept away by distractions.

WHERE VALUES COME FROM

Our values don’t come to us in our sleep. We don’t think them through consciously. Rarely do we even put them into words. But they exist nonetheless. Everyone is born into a certain set of circumstances, and our values are defined by what we experience. Were we born into hardship or luxury? Where did we receive praise? Parents and caregivers are often our loudest fans and critics. Though we might rebel in our teenage years, we are generally compelled to please and imitate those authority figures. Looking back...

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Part One: Let Go

- Part Two: Grow

- Part Three: Give

- Conclusion

- Appendix: The Vedic Personality Test

- Acknowledgments

- Author’s Note

- Notes

- Next Steps

- List of Searchable Terms

- About the Publisher