eBook - ePub

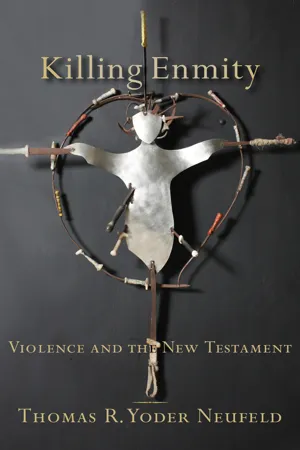

Killing Enmity

Violence and the New Testament

Yoder Neufeld, Thomas R.

This is a test

- 192 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Killing Enmity

Violence and the New Testament

Yoder Neufeld, Thomas R.

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Is the New Testament inherently violent? In this book a well-regarded New Testament scholar offers a balanced critical assessment of charges and claims that the Christian scriptures encode, instigate, or justify violence. Thomas Yoder Neufeld provides a useful introduction to the language of violence in current theological discourse and surveys a wide range of key ethical New Testament texts through the lens of violence/nonviolence. He makes the case that, contrary to much scholarly opinion, the New Testament is not in itself inherently violent or supportive of violence; instead, it rejects and overcomes violence. [Published in the UK by SPCK as Jesus and the Subversion of Violence: Wrestling with the New Testament Evidence.]

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Killing Enmity als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Killing Enmity von Yoder Neufeld, Thomas R. im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Théologie et religion & Critique et interprétation bibliques. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

1

‘Violence’ and ‘New Testament’

We begin our investigation with an exploration of what we mean with ‘violence’ and ‘New Testament’. It may seem obvious what these terms mean, but in actual fact there is a wide range of meanings persons give to these two concepts, and to the approaches taken to them. Given the brevity of this study, the limited number of texts and the limited attention we will be able to give them, this chapter will serve not only as an introduction to the theme but point the way to resources that can help further investigation.

‘Violence’

Reflecting dictionaries generally, the first meaning of ‘violence’ in the Oxford English Dictionary is as follows:

The exercise of physical force so as to inflict injury on, or cause damage to, persons or property; action or conduct characterized by this; treatment or usage tending to cause bodily injury or forcibly interfering with personal freedom.

Violence is intentional physical harm and injury. We think of crimes of violence such as battery or murder, or of war, in which massive harm is done to others, whether by soldiers or civilians. To state the obvious, ‘violence’, ‘violent’ and ‘to violate’ have unambiguously negative implications. Even when such violence is deemed necessary in certain circumstances, it is viewed as highly regrettable. Synonyms of violence are force, coercion, abuse, aggression, fighting, hostility, brutality, cruelty, carnage, ferocity, vehemence and many more. The dictionaries point out that sometimes ‘violence’ can denote vehemence of feelings that come to expression in gestures or words, even if they are not accompanied by physical harm, and that ‘violence’ can be used to designate someone’s use of language in improper ways, or even wilful distortion of the words of others, including texts. But intended physical harm is the primary lexical meaning.

Were violence as ‘intent to injure’ the sole way it is understood in our culture, this book would probably not have been written. More than once I have had to respond to the question, ‘You mean “Old Testament”, right?’ The common assumption is that the New Testament is generally against violence. Jesus’ teaching on non-retaliation in the Sermon on the Mount comes most quickly to mind. However, what counts as ‘violence’ has widened dramatically, with significant implications for how the New Testament relates to violence.

To illustrate, Johan Galtung coined the by now deeply entrenched terms ‘structural’ and ‘cultural violence’, showing that there is violence other than ‘direct’ violence engaged in and suffered by individuals.[1] Political and economic ways in which society is ‘ordered’ can violate whole peoples and classes. Robert McAfee Brown likewise expands the notion of violence:

Whatever ‘violates’ another, in the sense of infringing upon or disregarding or abusing or denying that other, whether physical harm is involved or not, can be understood as an act of violence. The basic overall definition of violence would then become violation of personhood.[2]

Such ‘an act that depersonalizes would be an act of violence’ and might not be obvious ‘except to the victim’.[3] Importantly, in such a case the determination of what constitutes violence has shifted from the intent of the perpetrator to the one who experiences it. Brown cites Brazil’s Dom Helder Camara’s notion of a ‘spiral of violence’, where ‘direct’ violence is often already a response to ‘structural’ (economic, racial, class) violence, a notion Richard Horsley has taken up on his Jesus and the Spiral of Violence.[4] Similarly, the late French sociologist and theologian Jacques Ellul identifies the conflict between economic classes as ‘violent competition’.

The violence done by the superior may be physical (the most common kind, and it provokes hostile moral reaction), or it may be psychological or spiritual, as when the superior makes use of morality and even of Christianity to inculcate submission and a servile attitude; and this is the most heinous of all forms of violence.[5]

These perspectives reflect the issues surrounding violence particularly during the 60s and 70s of the last century, when the threat of nuclear annihilation, revolution and the war in Vietnam established the context for a consideration of the relationship of violence and the New Testament. Was the ‘historical’ Jesus a ‘Zealot’? Did he harbour sympathies for resistance and revolutionary movements? Or was he resolutely anti-violent in his teachings on non-retaliation and love of enemies?[6] Do Paul’s famous words in Romans 13.1–7 regarding being subordinate to the authorities imply he was anti-revolutionary, thus supportive of state violence (‘sword’)? Or does ‘Romans 13’ furnish the grounds for resistance to an unjust and thus ultimately illegitimate regime? Is John’s Apocalypse a blistering prophetic critique against a violent Roman Empire? Or is it a fevered apocalyptic vision of divinely initiated end-time violence, providing theological cover for those dreaming of nuclear Armageddon?

The Vietnam War ended; the Cold War came to an end of sorts; revolutionary rhetoric disappeared from common discourse in the global North. The focus of ‘violence’ has since shifted to terrorism, especially when religiously motivated. More, ‘violence’ has come to be identified not only as deliberate physical harm or injury but also harm done to the environment, through economic inequalities, persistent gender inequalities, racial, sexual and class discrimination, and marginalization and intolerance in general, whether buttressed by state power, culture or religion and, more specifically, sacred texts. Not just ‘fundamentalism’, but religion more generally, has come under intense scrutiny on whether it is a resource against violence or whether it might not be an incubator for it. There is heightened sensitivity to the potential of religion not only to countenance violence but also to nurture and to incite it. Needless to say, this has brought also the New Testament to the attention of critics.

To complicate matters yet more, there is growing awareness of the role of power, social location and vested interests at work in human discourse. This has undermined confidence in interpreting texts as having a particular meaning and, at the same time, increased alertness to the way texts are themselves involved in the exercise and maintenance of power, often masking the violence at work in them. In a postmodern context, the very notion of authority, of revelation and the claim to universal validity fall under the suspicion of purveying violence, broadly conceived.

If the meaning of texts does not reside simply in the author’s intentions, which may or may not be accessible to the reader or interpreter in any case, but rather in the interaction between readers and the text, then a text becomes violent if the interpreter or the reader experiences or employs it as such. This is one aspect of the way in which the shift in determining whether some action or word is violent moves from actor to victim. Clearly texts can themselves fall victim to the use interpreters put them to. We speak frequently of ‘doing violence to a text.’ We might then also ask whether a text ceases to be ‘violent’ if readers do not ‘take it’ that way, or use it that way. For example, scholars might determine a text to be violent in its implications, but not taken that way by a believing community. Should one blame the community for not being faithful to the text’s violence?

Not surprisingly, this way of construing violence as very broad has had a significant impact on the question of the relationship between violence and the New Testament. It has widened the texts that ‘count’ in such an investigation, but it has also opened the door to much greater and more radical critique. As Jonathan Klawans points out, ‘the broader the definition [of violence], the easier it is to indict biblical texts and those who, guilty by association, deem them to be sacred’.[7] In Violence in the New Testament, for example, various authors explore ways in which the documents of the New Testament are implicated in the violence of ‘empire’, even as these writings attempt to varying degrees to escape or critique it.[8] The massive four-volume The Destructive Power of Religion,[9] which contains many articles focused on the New Testament, adds psychology to the mix of criticism, exploring, among other things, the personality (disorders) of Jesus and Paul, the destructive effects of the intolerance in pronouncements of judgement and the violence deemed to be inherent in claims of revelatory truth.

Feminists have drawn attention not only to what they see as the implicit violence in the suppression of memory of the role women played in the early decades of the Church[10] but also to what they consider to be dimensions of the religion reflected in the New Testament as ‘dangerous to [women’s] health’.[11] In particular they have focused on texts requiring subordination of women to men, on what is deemed to be the valorization of suffering and, closely related, on the role of the death of Jesus in atonement and salvation. Some see it as a kind of ‘divine child abuse’,[12] viewing the violence of the cross as anything but ‘redemptive’.

This is by no means a concern only of feminists. Walter Wink has made the critique of ‘redemptive violence’ central to his work on the New Testament,[13] as has the French anthropologist and literary critic, René Girard, whose attention has focused on the sacrificial dimensions of religion, in particular of atonement theories in Christian theology, viewing sacrifice as participation in deep-seated violence endemic to human culture.[14]

If one enquires about the origin of violence, the explanations are again diverse. René Girard sees it as emerging from ‘mimetic rivalry’,[15] in effect from wanting what the other wants. This leads ultimately to murder and then to the various mechanisms to mask that murder and to contain the resulting cycle of violence, including scapegoating and sacrifice. In short, violence adheres to the very core of religion, particularly in the sacrificial and scapegoating mechanisms he sees as central to religion.

Hector Avalos has suggested, rather, that violence emerges from scarce resources and the deliberate restricting of access.[16] With respect to the New Testament, the restriction of salvation only to the elect, or only to believers, thus renders it violent at its very core.

Others propose that human beings are ‘hard-wired’ by nature for competition and rivalry for what it takes to live, and are thus predisposed to violence. Nature is ‘red in tooth and claw’, in Alfred Lord Tennyson’s words.[17]

Jacques Ellul sees violence as reflective of nature, yes, but of a fallen and corrupted nature, an inextricable aspect of the bleak ‘order of necessity’. Violence is not only sin but also rooted in primordial sin that pervades the way things are. With characteristic decisiveness, Ellul sees violence as therefore ‘absolutely’ prohibited for a Christian, as is any justification of violence, precisely because the Christian is ‘free’ from the necessity of the fallen order.

[Christians] must struggle against violence precisely because, apart from Christ, violence is the form that human relations normally and necessarily take . . . If we are free in Jesus Christ, we shall reject violence precisely because violence is necessary! . . . And mind, this means all kinds and ways of violence: psychological manipulation, doctrinal terrorism, economic imperialism, the venomous warfare of free competition, as well as torture, guerrilla movements, police action.[18]

(emphasis added)

Some have pushed back against such a wide construal of violence. Glen Stassen, for example, wishes to establish a thoroughgoing peaceable ethic based on the Sermon on the Mount, while recognizing the need for constraints and even a modicum of force in the interests of protection.[19] Without wishing to downplay the variety of ways persons can mistreat and abuse each other, putting a mugging and a forceful pulling of a person out of danger into the same category is seen as undercutting meaningful ethical discernment and debate.

Our brief survey on the meaning of ‘violence’ suggests that no one definition is by itself operative in public discourse. While there is general agreement that Jesus and the writers of the New Testament for the most part prohibit physical violence, the pervasive presence of warnings of judgement for those who do not live in accordance with the will of God, or who do not confess Jesus as Lord and Messiah, are seen to constitute not just the threat of violence in the future but a form of verbal violence in the present. The clear delineation between believers and unbelievers, between good and bad, are seen to create a mindset predisposed to violence. The prominence of the theme of suffering is under suspicion as valorizing violence, even if the violence is suffered rather than meted out. In the eyes of many the New Testament is androcentric and misogynistic, and thereby violent. Jonneke Bekkenkamp and Yvonne Sherwood insist that pervading the New Testament is a kind of ‘domestic violence’, that is, ‘violence not only as violation/abuse of essentially good material’ but violence taking place ‘at the very heart’ of the New Testament.[20]

These are deeply vexing matters, partly because the meaning of ‘violence’ is not possible to delineate carefully, and most especially because the meaning of texts and their effect is not thought to reside so much in the intentions of the authors as in the interplay between readers and texts located in various contexts.[21] In his Peace and Violence in the New Testament, Michel Desjardins puts it quite simply: ‘Non-physical types of peace and violence cannot be delimited with precision.’[22] However regrettable, to work with a wide definition of violence ‘means giving up the possibility of arriving at a specific understanding of violence that is shared by all’.[23]

‘New Testament’

If ‘violence’ is a complex reality so is ‘New Testament’, and if the New Testament is complex so are the communities invested in it, and the interpreters serving those communities, whether within the Church or in the academy.

As is well known, ‘New Testament’ refers to the 27 diverse documents making up the latter part of the Christian Bible. While now the second part of a ‘book,’ it is a composite of diverse narratives of Jesus’ life, ministry, teaching, death, and resurrection, of letters written by emissaries (‘apostles’) and others unknown to us and addressed to diverse groups of adherents throughout the eastern half of the Roman Empire, as well as an apocalypse, penned by a prisoner languishing on an island in the Aegean. Written over roughly a century, from mid-first to mid-second century, these documents reflect an astonishing period of change: from a Jewish renewal movement, more or less on the radical edges of Jewish society, to increasingly non-Jewish (Gentile) Hellenistic circles of devotees of this Jewish messiah; from rural and small village life to cosmopolitan urban diversity; from the creativity and ‘holy chaos’ of an intensely future-oriented and expectant movement to increasingly routinized and institutionalized life more suited to a ‘long haul’.[24]

We should thus expect to find diverse dimensions of what counts as ‘violence’ reflected on the pages of the New Testament. It is not an exaggeration to say that violence pervaded the world of Jesus and his followers. Herodian and Roman imperial rule, sparking sporadic resistance, and culminating in the catastrophic war against Rome in 66–70 CE, created an ambience of pervasive violence.[25] In addition to the political and military brutalities, the growing disparities between rich and poor, landowners and landless, form a vivid background to Jesus’ parables, for example. The conflict between the rural poor and the temple state centred in Jerusalem is reflected in the final days of Jesus’ life. If what counts as violence is marginalization on the basis of religion and sex, the pages of the Gospels reflect the pervasiveness of such violence as well. The presence in the narratives of Jesus’ life of lepers, prostitutes, tax collectors, haemorrhaging women, and Samaritans testifies to what can fairly be called ‘structural,’ ‘cultural’ and ‘religious violence’. Equally, the landowners, slaveholders, centurions, suspicious and judgemental religious leaders, local kings and Roman overlords populating the narratives of Jesus’ life and his parables represent those in charge of maintaining an order soaked in violence. Violence is seldom if ever beyond the horizon in the Gospels.

When we move beyond Palestine into the wider Mediterranean world, and view that world from the vantage point of believers in Jesus, we see that it too is marked by pervasive violence. Even when the Jesus movement benefited from the order and ‘peace’ the security state brought them, making possible the rapid spread of the movement, the violence of that system was never far out of sight. Apart from the hostility and even physical violence early Jesus-believers experienced at the hands of...

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- 1. ‘Violence’ and ‘New Testament’

- 2. Turn the cheek and love your enemies!

- 3. Forgive, or else!

- 4. Violence in the temple?

- 5. Atonement and the death of Jesus

- 6. Subordination and violence

- 7. Divine warfare in the New Testament

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index of biblical references

- Index of authors

- Index of subjects

- About the author

- Notes

- Back cover

Zitierstile für Killing Enmity

APA 6 Citation

[author missing]. (2011). Killing Enmity ([edition unavailable]). Baker Publishing Group. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/2050867/killing-enmity-violence-and-the-new-testament-pdf (Original work published 2011)

Chicago Citation

[author missing]. (2011) 2011. Killing Enmity. [Edition unavailable]. Baker Publishing Group. https://www.perlego.com/book/2050867/killing-enmity-violence-and-the-new-testament-pdf.

Harvard Citation

[author missing] (2011) Killing Enmity. [edition unavailable]. Baker Publishing Group. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2050867/killing-enmity-violence-and-the-new-testament-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

[author missing]. Killing Enmity. [edition unavailable]. Baker Publishing Group, 2011. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.