eBook - ePub

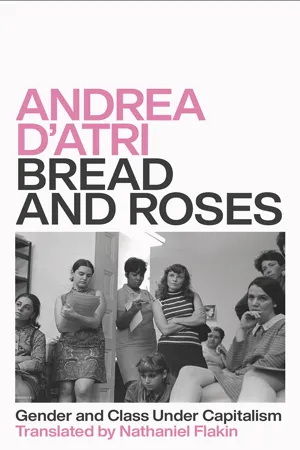

Bread and Roses

Gender and Class Under Capitalism

Andrea D'Atri, Nathaniel Flakin

This is a test

- Spanish

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Bread and Roses

Gender and Class Under Capitalism

Andrea D'Atri, Nathaniel Flakin

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Is it possible to develop a radical socialist feminism that fights for the emancipation of women and of all humankind?

This book is a journey through the history of feminism. Using the concrete struggles of women, the Marxist feminist Andrea D'Atri traces the history of the women's and workers' movement from the French Revolution to Queer Theory. She analyzes the divergent paths feminists have woven for their liberation from oppression and uncovers where they have hit dead ends.

With the global working class made up of a disproportionate number of women, women are central in leading the charge for the next revolution and laying down blueprints for an alternative future. D'Atri makes a fiery plea for dismantling capitalist patriarchy.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Bread and Roses als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Bread and Roses von Andrea D'Atri, Nathaniel Flakin im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Politics & International Relations & Political Freedom. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

1

Grain Riots and Civil Rights

Women, wake up; the tocsin [alarm bell] of reason sounds throughout the universe; recognize your rights.

—Olympe de Gouges

BREAD, CANNONS, AND REVOLUTION

In the epoch of the struggles against feudal absolutism and of the consolidation of the bourgeoisie as a ruling class, a wave of peasant revolts passed through Europe. From the sixteenth century onwards, these revolts continued without interruption, and only ended with the formation of modern nation-states in the nineteenth century. Women were the protagonists of these rebellions that frequently led the masses to use violence. On numerous occasions, it was women who led them.

In 1709 and 1710, at the dawn of the eighteenth century in England, the housewives of Essex led riots against their living conditions, together with the miners of Kingswood and the fishermen of Tyneside. In 1727, the tin miners of Cornwall and the coal miners of Gloucestershire did the same. In 1766, the revolts spread across Great Britain. In 1725 in France, there were revolts in Caen, Normandy, and Paris. In 1739 and 1740, the riots spread to Bordeaux, Caen, Bayeaux, Angoulême, and Lille. In 1747, the masses rose up in Toulouse and Guyenne. In 1752, in Arles, Bordeaux, and Metz; in 1768, in Le Havre and Nantes. Finally, in 1774 and 1775, the so-called “Flour War” spread throughout northern France.

These riots imposed “popular taxation” (price controls) and also raised political demands. The burden of rents and taxes, the shortage of food, the loss of rights, and the abuses by the nobility were the central motives for the rebellions. It was also very common for revolts to be caused by an increase in the price of wheat and bread, by the competition of foreign workers who threatened the job opportunities of native workers, or by the speculation of merchants who monopolized scarce goods.

According to the historian E.P. Thompson, women were often the main instigators of riots.

In dozens of cases it is the same—the women pelting an unpopular dealer with his own potatoes, or cunningly combining fury with the calculation that they had slightly greater immunity than the men from the retaliation of the authorities.1

In all cases, the means of action were similar:

The small-scale, spontaneous action might develop from a kind of ritualised hooting or groaning outside retailers’ shops; from the interception of a wagon of grain or flour passing through a populous centre; or from the mere gathering of a menacing crowd.2

Thompson recounts numerous anecdotes, for example, in 1693, when women went to the Northampton market with knives hidden in their corsets to force the sale of grain at a price they had set themselves. According to contemporary reports, the people of Stockton rose up in 1740 after being incited by a woman armed with a stick and a bugle. Among these stories is also one about a justice of the peace who once complained that it was women who incited the men to fight, and who, like “perfect furies,” beat him on the back.

On October 5, 1789, in France, the women of Les Halles and Saint Antoine, two crowded neighborhoods in Paris, demanded bread in front of the city hall and marched toward Versailles, where the kings resided. This women’s march became one of the motors of the revolutionary mobilizations that led to what has entered into history under the name of the “French Revolution.”

As in other historical processes, the great French Revolution, which united all classes and social sectors in the struggle against absolutism, began with a revolt led by the women of the poor neighborhoods of Paris.

We will allow ourselves to quote extensively from a text by Alexandra Kollontai, in which she points to the role of women throughout the revolution:

The “women of the people” in the provinces of Dauphiné and Brittany were the first to challenge the monarchy. […] They took part in the election of deputies for the Estates General and their votes were universally accepted. […] The women of Angers drew up a revolutionary manifesto against the tyranny of the royal house, and the proletarian women of Paris took part in the storming of the Bastille, entering with weapons in hand. Rose Lacombe, Luison Chabry, and René Ardou organized the women’s march on Versailles and brought Louis XVI to Paris under strict guard. […] The women of the fish market sent a delegate to the Estates General to “encourage the deputies and remind them of the women’s demands.” “Do not forget the people!” called out this delegate to the 1,200 members of the Estates General, that is, the National Assembly of France. […] Long after the collapse of the revolution, the memory of the horribly cruel and bloodthirsty “tricoteuse” [knitting women] continued to haunt the dreams of the bourgeoisie. But who were these “knitters,” these furies, as the oh-so-peaceful counter-revolution liked to call them? They were artisans, peasants, laborers in the home or the workshop, who suffered from hunger and all sorts of torments, and hated the aristocracy and the ancien régime with all their hearts and strength. Confronted with the luxury and waste of the arrogant and idle nobility, they reacted with a healthy class instinct and supported the most militant vanguard for a new France, in which all men and women would have a right to work and children would not starve to death. In order to avoid wasting time unnecessarily, these honest patriots and diligent workers knit stockings not just at festivities and demonstrations, but also at the sessions of the National Assembly and at the foot of the guillotine. They did not knit these stockings for themselves, by the way, but for the soldiers of the National Guard—the defenders of the revolution.3

The newspapers of the time describe some of the heroic women of the demonstrations of 1789 that led to the revolution, such as

that 18-year-old girl who was seen fighting, dressed as a man, next to her lover, and that coal seller who, after the siege, is searching for the body of her son and responds with haughtiness to those who comment about her serenity: “In what more glorious place could I go to look for him? If he gave his life for his fatherland, is he not blessed?”4

Marie-Louise Lenoël, later a member of the National Assembly, remarks on these episodes:

The first assembly attended only by women took place at eight o’clock in the morning in front of the city hall, in order to find out why it was so difficult to get bread and at such a high price; other women demanded that the king and queen should come and settle in Paris.5

According to another account from the time, women:

tie ropes to the chassis of the cannons, but since they are cannons from ships, this artillery is difficult to move. So the women requisition carriages, load their cannons onto them, and tie them down with cables, loading gunpowder and cannonballs as well. Some lead the horses and others, seated on the cannons, carry the fearsome fuse and other instruments of death in their hands. At the beginning of the march at the Champs Élysées, their number already exceeds 4,000, and they are escorted by 400 or 500 men, who had armed themselves with everything they could find.6

The women of the Grenoble region, for their part, sent an insolent letter to the king: “We are not willing to bear children destined to live in a country subjected to despotism.”7

There were also women whose names transcended this historic episode, like Madame Roland or the journalist and author Louise Robert-Kévalio, who sympathized with the moderate wing of the Girondins. Or Théroigne de Méricourt, who called on the people to take up arms, took part in the storming of the Bastille, and received a sword from the National Assembly as a reward for her courage. As legend has it, on October 5, 1789, she went ahead of the march on Versailles and entered the city on horseback, dressed in red, trying to win the women for the revolutionary cause.

FEMALE CITIZENS DEMAND EQUALITY

In 1789, when the National Assembly voted for the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, two documents about women appeared. On January 1, 1789, the anonymous pamphlet Petition of Women of the Third Estate to the King was published. The other, titled Notebook of Women’s Grievances and Demands, signed by one Madame B.B., proclaims in one of its paragraphs:

Gather, daughters of Caux, and you, female citizens of provinces governed by customs as unjust as they are ridiculous, go to the feet of the monarch, the best of kings, take an interest in everything that surrounds him, demand, solicit the abolition of a law that reduces you to poverty as soon as you are born.8

The best-known manifestos for women’s rights are On the Admission of Women to the Rights of Citizenship by the Marquis de Condorcet,9 and the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen by the legendary Olympe de Gouges, from 1790 and 1791 respectively. Olympe de Gouges’ real name was Marie Gouze. She was born in 1748 and in 1765 married an officer named Pierre Aubry with whom she likely had a son. She later embarked on a career as a writer, chiefly of plays. In 1791, when the king was arrested, she declared: “In order to kill a king it is not enough to cut off his head; he lives on long after his death; he is only truly dead once he has survived his fall.” In a pamphlet, she proposed holding a referendum about the following alternatives: a single and indivisible republican government, a federal government, or a monarchic government. For this reason, she was arrested and guillotined on November 3, 1793.

It was not only in France that demands for the rights of female citizens were raised. In England, Mary Wollstonecraft published her Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792, lamenting that women “are only considered as females, and not as a part of the human species.”10 Wollstonecraft did not limit herself to demands for political rights; she spoke up against society’s hypocrisy and against inequality. She had been born in England in 1759 and received instruction from a Protestant pastor. Her first job was as a governess, an experience that led her to write Thoughts on the Education of Daughters. She defended the French Revolution and moved in Girondin circles in Paris. Other works she wrote include A Vindication of the R...

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface to the English Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Biography

- Introduction

- 1. Grain Riots and Civil Rights

- 2. Bourgeois Women and Proletarian Women

- 3. Between Philanthropy and Revolution

- 4. Imperialism, War, and Gender

- 5. Women in the First Workers’ State in History

- 6. From Vietnam to Paris, Bras to the Bonfire

- 7. Difference of Women, Differences Between Women

- 8. Postmodernity, Postmarxism, Postfeminism

- By Way of Conclusion

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index

Zitierstile für Bread and Roses

APA 6 Citation

D’Atri, A. (2020). Bread and Roses (1st ed.). Pluto Press. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/2059055/bread-and-roses-gender-and-class-under-capitalism-pdf (Original work published 2020)

Chicago Citation

D’Atri, Andrea. (2020) 2020. Bread and Roses. 1st ed. Pluto Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/2059055/bread-and-roses-gender-and-class-under-capitalism-pdf.

Harvard Citation

D’Atri, A. (2020) Bread and Roses. 1st edn. Pluto Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2059055/bread-and-roses-gender-and-class-under-capitalism-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

D’Atri, Andrea. Bread and Roses. 1st ed. Pluto Press, 2020. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.