eBook - ePub

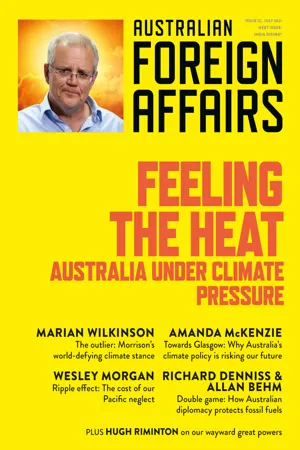

AFA12 Feeling the Heat

Australia Under Climate Pressure

Jonathan Pearlman, Jonathan Pearlman

This is a test

- 144 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

AFA12 Feeling the Heat

Australia Under Climate Pressure

Jonathan Pearlman, Jonathan Pearlman

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

"Australia's climate and energy policy is a 'toxic time bomb'... Now Morrison, feeling the heat from Australia's allies, from growing numbers in the business community and from a majority of voters, needs to work out how he will handle that bomb." MARIAN WILKINSON The twelfth issue of Australian Foreign Affairs examines the growing pressure on Australia as global and regional powers adopt tough measures to combat climate change. Feeling the Heat looks at the consequences of splitting from the international consensus, and at how a climate pivot by Canberra could unlock new diplomatic and economic opportunities.

- Marian Wilkinson probes how Canberra is responding to international pressure on climate and asks if we are at a political tipping point.

- Wesley Morgan warns that Australia's climate policy is undermining our Pacific relationships and proposes a path for rebuilding trust.

- Richard Denniss and Allan Behm expose Australia's efforts to obstruct international climate action and to support fossil fuel exports.

- Amanda McKenzie uncovers how Australia's climate policy impedes its diplomacy and how to address this malaise.

- Anthony Bergin and Jeffrey Wall outline a solution to Australia's dwindling business ties in the Pacific.

- Hugh Riminton examines the future contours of the Asian Century.

- Michelle Aung Thin discusses the brutal Myanmar coup and its impact on the nation.

PLUS Correspondence on AFA11: The March of Autocracy from Fergus Ryan, Kevin Boreham and Yun Jiang.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist AFA12 Feeling the Heat als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu AFA12 Feeling the Heat von Jonathan Pearlman, Jonathan Pearlman im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Politique et relations internationales & Géopolitique. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Correspondence

“Enter the Dragon” by John Keane

Fergus Ryan

In his dense yet sprawling essay “Enter the Dragon” (AFA11: The March of Autocracy), political scientist John Keane explores the features of what he dubs China’s “phantom democracy” and looks ahead to its implications for the country’s expanding “galaxy empire”.

Keane’s contention, first stated in his 2017 book When Trees Fall, Monkeys Scatter, is that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) maintains its power in China not so much through the barrel of a gun as through its use of opinion polls, village elections and social media as a listening post to gauge what the citizenry wants. “In the PRC, state violence and repression are masked,” Keane writes. “Coercion is calibrated: cleverly camouflaged by elections, public forums, anticorruption agencies and other tools of government with a ‘democratic’ feel.”

What Keane misses is that many of the features of his imagined “phantom democracy” in China are either relics of the “semi-liberal” era under General Secretary Hu Jintao, which dated from 2002 to 2012, or have long been mirages that are dissipating as the country grows strong enough to invest more heavily in the tools and infrastructure required for maintaining ideological control.

According to Keane, China’s “phantom democracy” can be seen in the behaviour of Xi Jinping, who presses the flesh like politicians in liberal democracies, as well as in village elections and the spread of “consultative democracy” into “city administration and business”. This approach, he suggests, may soon extend to how China deals with the rest of the world. China’s leaders may be able to succeed “not only in harnessing phantom democratic mechanisms at home to legitimate and strengthen their single-party rule, but also abroad, in the far-flung districts of their empire”.

Before we get too carried away with imagined futures, it’s instructive to note how Beijing is currently attempting to keep other countries in the orbit of its “galaxy empire”. The Chinese embassy in Canberra’s leak of “fourteen disputes” to the Australian media in November 2020 is a good place to start. More a list of demands than disputes, it included calls for Canberra to muzzle our free press, suppress news critical of China, sell off strategic assets and roll back laws designed to counter Beijing’s covert influence operations here.

The release of the demands and Beijing’s subsequent deployment of coercive economic leverage on Australia has flung us further away from China’s gravitational pull. Since its release, the Morrison government has doubled down on a strategy of selective decoupling from China by cancelling the Victorian government’s Belt and Road Initiative agreement with Beijing. The Northern Territory’s ninety-nine-year lease of Darwin Port to Chinese company Landbridge may very well be next.

The title of Keane’s 2017 book is taken from a Chinese proverb he says is top of mind for the CCP leadership from Xi Jinping down, because they fear that if the party falls, the economic, social and political repercussions for the country would be catastrophic. Another simian-related Chinese idiom is no doubt on the tip of their tongues as they consider how to fend off this calamity: killing the chicken to scare the monkeys.

It’s doubtful that Beijing ever expected Canberra to reverse course on any of the grievances leaked by the embassy. In the eyes of China’s leaders, Australia is the chicken, and they fully intend to make an example of us as a warning to other countries considering challenging the People’s Republic of China. The reality is that the CCP is no more interested in winning over the consent of other countries than in gaining the approval of its own citizens. You either fall in line or become tomorrow’s roast chook.

No sooner had Keane published his book in 2017 than the wheels of his argument began to fall off. Time limits on officeholders was included as a feature of his “phantom democracy”, but does not make an appearance in this recent iteration of his argument after Xi Jinping effectively appointed himself emperor for life. But the linchpin of Keane’s “phantom democracy” argument is the country’s use of village elections as a form of “consultative democracy”. The problem with this argument is that village elections have been systematically undermined by Beijing for twenty years and have now been effectively abolished.

First introduced in the 1980s, village elections proved an effective way of improving local governance, but were steadily sidelined in importance as China’s economy grew and the central government was able to dramatically increase investment in its bureaucratic capacity, according to long-time election watchers Monica Martinez-Bravo of CEMFI (Center for Monetary and Financial Studies), Gerard Padró i Miquel of Yale University, Nancy Qian of Northwestern University and Yang Yao of Peking University. “Why would the Chinese government in the 2000s systematically undermine local elections, which we document to have been effective in improving local governance?” the quartet write in their 2017 paper “The Rise and Fall of Local Elections in China”. “Our study suggests a simple explanation: if the autocrat can afford better direct control, then it does not need to suffer the policy costs associated with electoral monitoring.”

The same principle is at play in Beijing’s attempts to bring its bustling social media sphere to heel. Under Hu, online platforms such as Weibo acted as a pressure valve whenever public opinion boiled over. Under Xi, more direct control is possible: surveillance has increased, and the censorship burden has shifted from the internet companies to the users themselves. The project is in a nascent form, but the contours are clear – the internet is to be harnessed as a tool of omniscient control, not as some passive listening post feeding back to the Mandarins in Zhongnanhai.

It’s evident to anyone engaged with Chinese social media that the already narrow space to speak freely online has shrunk considerably under Xi Jinping. In February 2021, China’s internet regulator started to require bloggers to have a government-approved credential before they could publish on a wide range of subjects that extend beyond politics and military topics to health, economics, education and judicial matters. That’s just one of the latest examples of the CCP’s attempts to increase its stranglehold over the Chinese internet. But the strategy goes beyond mere censure. It’s now no longer enough to steer clear of certain topics; it’s everyone’s responsibility to emphasise uplifting messages over criticism – referred to by the CCP as spreading “positive energy” – and engage in national boosterism or “telling China’s story well”, as Xi instructed in his report to the 19th CCP National Congress in 2017.

Until the early years of the Xi era there had always been enough of a democratic patina in the party’s rhetoric and the PRC’s structure to fool the odd CEO, prime minister or visiting scholar. Not only does the PRC have a parliament; it also has a judiciary and eight legally recognised parties. This belief has long since dissipated from boardrooms and party rooms and yet appears to persist in academia. One wonders how long it will be before some scholars stop pretending China is a democracy, phantom or not.

Fergus Ryan is an analyst with the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s

International Cyber Policy Centre.

International Cyber Policy Centre.

Kevin Boreham

In his tough-minded essay on China’s return to world pre-eminence, John Keane assesses how China “throws its cultural weight around on the global stage” while domestically “[t]he slightest whiff of a challenge to the CCP’s power can bring down the hammer”. China’s aggressive rejection of human rights is the result of three decades of indifference to its human rights violations from the international community, including Australia, as nations pursued the riches flowing from China’s economic opening.

In March 2021, geopolitical strategist Robert D. Kaplan wrote in Foreign Policy, “China knows that in a world where everyone trades with it – and therefore requires, at some level, its approval – states will pay lip service to human rights while acting on their economic interests.”

Western and other like-minded states, including Australia, have long acquiesced in excluding China’s human rights violations from UN action. Back in 1997, China blocked a resolution over its human rights abuses in the UN Commission on Human Rights, the forerunner of the UN Human Rights Council. The United States and the European Union sent signals even before the commission meeting that they would not stand up to China over this: the EU procrastinated on how it would deal with the issue, while Washington indicated that Sino–US relations would not be “held hostage” to human rights concerns. Since then, there has been no effective consideration of holding China to account in an international forum.

China regards Geneva, where the UN Human Rights Council meets, as its front line. No one who has observed China’s tough, effective and well-resourced efforts to suppress any consideration of its human rights record could doubt that China takes the deliberations of UN human rights bodies very seriously.

Keane aptly shows that the Chinese leadership embraces a “phantom democracy” governing style that is entirely superficial and entirely geared to maintain the control of the CCP. His discussion of the mechanisms of control – data-harvesting through the People’s Daily Online Public Opinion Monitoring Centre and opinion polling through organisations such the Canton Public Opinion Research Centre (C-por) – is illuminating.

China’s strategy in multilateral bodies, particularly the Human Rights Council, complements the manipulation of domestic opinion that Keane identifies. China builds common interests with other states that also have poor records of democratic governance and observance of human rights. A 2017 Human Rights Watch report observed China’s tendency to marshal support from developing countries “by strategically positioning itself as [their] champion” and “defending them in the Council when they receive specific attention”.

There has been token pushback against China’s aggressive stance over criticism of its human rights record. In March 2016, Australia issued a joint statement with eleven other states at the Human Rights Council criticising China’s “deteriorating human rights record”. In July 2019, twenty-two countries, including Australia, formally urged China to end its mass arbitrary detentions and related violations against Muslims in the Xinjiang region.

Most significantly, during the latest council meeting, in March 2021, seventy countries signed a statement by Belarus that supported China’s policy towards Hong Kong, noting that “non-interference in internal affairs of sovereign states is an important principle enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations and a basic norm governing international relations”. A joint statement led by the United States and signed by fifty-three nations including Australia rebutted this position, asserting that “states that commit human rights violations must be held to account”. This statement reflects the human rights policy of the Biden–Harris administration. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, speaking at the launch of the department’s annual “Country Reports on Human Rights Practices” on 30 March, confirmed that “we will bring to bear all the tools of our diplomacy to defend human rights and hold accountable perpetrators of abuse”.

We will have to see how this determination to hold to account human rights violators plays out in relation to other national interests. For the moment, as the International Service for Human Rights commented about previous joint statements, they “fall short of decisive action”.

Meanwhile, China has skilfully proposed alternatives to the Geneva process. A diplomat whose country engages in bilateral human rights dialogues with China told Human Rights Watch in 2017 that some observers thought the Chinese government used approval for the next human rights dialogue “like a cookie”, agreeing to a date only when the other parties had refrained from publicly issuing human rights criticism.

In 1997, Australia agreed to start a formal and regular bilateral dialogue on human rights with China. The dialogue has become mute: the last round of the Australia–China Human Rights Dialogue was held in February 2014. This preference for more easily controllable bilateral channels on human rights was implied in the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper, which states that “Australia will promote human rights through constructive bilateral dialogue”.

These weak reactions to China’s human rights violations have reinforced what Keane calls “China’s greatest flaw: its lukewarm and contradictory embrace of public accountability mechanisms”. They show the need for the process fellow essayists in the issue, Natasha Kassam and Darren Lim, urge: “working with partner states to develop clear parameters of unacceptable behaviour [by China], particularly on … egregious human rights violations”. More generally, they show the dire consequences of soft options in responding to gross human rights violations.

Kevin Boreham has been DFAT assistant secretary, South-East Asia branch, and assistant secretary, International Organisations branch, and taught international law at the Australian National University.

John Keane responds

I thank Kevin Boreham and Fergus Ryan for their comments on my essay. Both authors are silent about its principal aim – to offer a fresh interpretation of China’s emerging role as a global empire. They are instead exercised by single issues. Their analysis of these is disappointing, and the consequences less than satisfying.

Kevin Boreham, a former public servant and scholar of international law, is preoccupied with human rights. His comments are important, for they remind us of the continuing political importance of the marriage of the languages of human rights and democracy that happened for the first time during the late 1940s. The crowning achievement of that decade was the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Drafted in 1947–48 in response to genocide in the aftermath of global war, its preamble spoke of “the inherent dignity” and “the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family”. The declaration – the most translated document ever, available nowadays in 500 languages – proclaimed a series of inalienable rights for everyone, “without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status”.

Boreham is aware that the project of guaranteeing that every human being enjoys the right to have rights remains utopian. It is unfinished business – he could have added – often because of the human rights games played by states. Human rights attract swindlers, prevaricators and peddlers of double standards. Boreham wags his finger at China’s “aggressive rejection of human rights”. He underscores China’s “tough, effective and well-resourced efforts to suppress any consideration of its human rights record”. He has a point, but things are more complicated than his let’s-pick-a-fight-with-China reasoning supposes. It should be remembered that China has consistently emphasised the social dimensions of human rights. In this it finds justification in the wording of the original declaration, which envisaged a world in which human beings enjoy “freedom from fear and want”. It’s why vaccines, healthcare, education, transportation and anti-poverty programs are among China’s policy priorities at home and abroad. Human rights in this selective sense are its thing – and a key reason why the PRC regime generates loyalty at home and respect abroad, in such regions as Central Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Worth bearing in mind too is that there are moments when China takes the lead on gross human rights abuses, as happened recently when China, president of the Security Council for the month of May 20...

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Editor’s Note

- Marian Wilkinson: The Outlier

- Wesley Morgan: Ripple Effect

- Richard Denniss and Allan Behm: Double Game

- Amanda McKenzie: Towards Glasgow

- The Fix: Anthony Bergin and Jeffrey Wall on How Australia Can Boost Business Ties with the Pacific

- Reviews

- Correspondence

- The Back Page by Richard Cooke

- Back Cover

Zitierstile für AFA12 Feeling the Heat

APA 6 Citation

Pearlman, J. (2021). AFA12 Feeling the Heat ([edition unavailable]). Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/2088143/afa12-feeling-the-heat-australia-under-climate-pressure-pdf (Original work published 2021)

Chicago Citation

Pearlman, Jonathan. (2021) 2021. AFA12 Feeling the Heat. [Edition unavailable]. Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd. https://www.perlego.com/book/2088143/afa12-feeling-the-heat-australia-under-climate-pressure-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Pearlman, J. (2021) AFA12 Feeling the Heat. [edition unavailable]. Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2088143/afa12-feeling-the-heat-australia-under-climate-pressure-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Pearlman, Jonathan. AFA12 Feeling the Heat. [edition unavailable]. Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd, 2021. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.