![]()

PART I

The Problem Persists

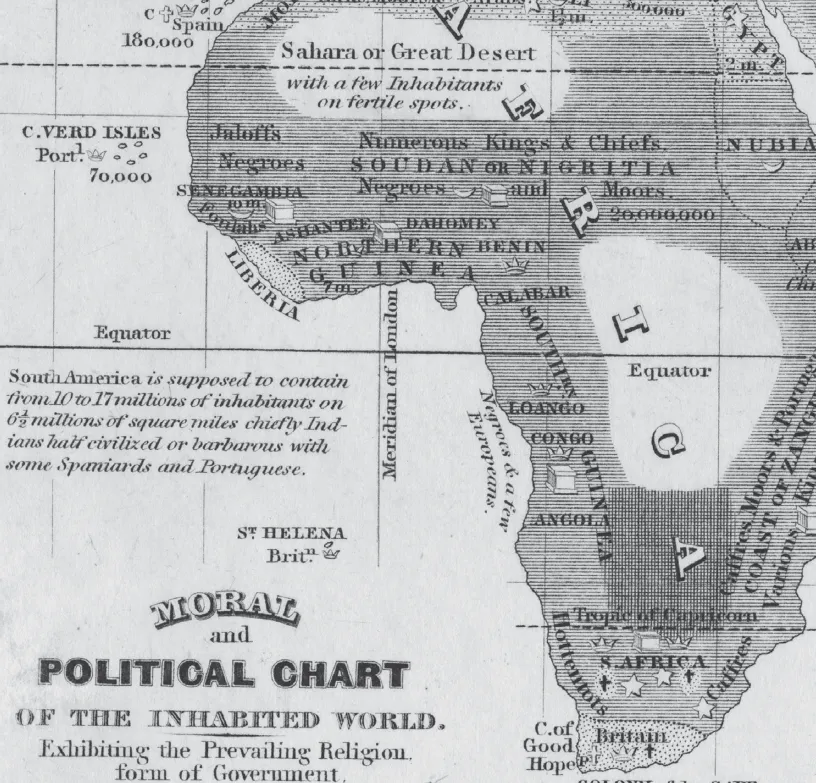

Moral and Political Chart of the Inhabited World (1845)

Creator: William Channing Woodbridge

Source: The Cornell University PJ Mode Collection of Persuasive Cartography.

![]()

1

Dark History

Men also, and by his suggestion taught,

Ransacked the centre, and with impious hands

Rifled the bowels of their mother Earth

For treasures better hid. Soon had his crew

Opened into the hill a spacious wound,

And digged out ribs of gold. Let none admire

Paradise Lost1

This quote from Milton’s Paradise Lost describes the fallen angel Mammon, who values earthly treasure over all other things. Milton is not subtle in describing a doomed and evil character as the original miner who passes the practice on to man. This is an early portrayal of mining and its association with sin.

Mining and conflict often run together. The extractive industry is filled with significant human rights disputes, environmental concerns and, in some cases, has even led to warfare. These concerns date back to at least the sixteenth century with the global ascent of the Spanish Empire. Prior to the Spanish conquest of New Spain, primitive mining techniques had been used on a small scale by the Indigenous peoples of the Americas since 1500 BC.2 The Spanish began mining precious metals on a commercial scale after the conquest of the Aztec and Tarascan states in the sixteenth century, enslaving large numbers of Indigenous people to work in their mines, including men, women and children.3 These slaves were branded on their cheek to demonstrate that they were the property of the Spanish Crown.4

Beyond the practice of forced labour, the Spanish looted palaces, graves and other sacred places for precious ceremonial artifacts.5 Large tracts of forests were cut to make charcoal for fueling smelters as part of the mining operations. This led to the significant depletion of vegetation surrounding the mines. A special mining ordinance was enacted in 1542 for one mine in modern day Mexico to prevent any further logging.6

Enslavement and environmental damage were not the only injustices the Spanish inflicted on the local Indigenous population. Aggressive missionary activities, the occupation of lands to block foreign aggression and the cultivation of crops on the most fertile soil for European markets were also the effects of Spanish colonisation in the Americas.7

The ‘New Laws’ of 1542 abolished slavery in New Spain partially on account of the advocacy of the Dominican friar, Bartolomé de las Casas.8 However, the abolition was not enforced effectively and the institution of slavery continued into the 1550s.9 During this period, Spain endured difficult economic times on account of a shortage of silver within its boundaries due in part to its exportation by Genoese and German merchants. The diminishing volume of precious metal imports and the rise of illegal exporting negatively impacted the prosperity of Spain.10 Believing there was a link between their economic misfortune and the exportation of silver, the Spanish Crown began to embrace a form of mercantilism known as bullionism, a concept based on the notion that wealth is ultimately bound up in precious metals.11

This belief led to a growing demand for silver in Spain during the seventeenth century. For example, from 1621 to 1631, spending on silver doubled every year by the Spanish Crown.12 In order to meet the growing demand for precious metals, the Spanish devised various methods for ramping up production and output from their mines in New Spain.13

Given that slavery was now abolished, the Spanish needed to create a new method to exploit the local Indigenous population as a source of labour. They did so through a system known as the mit’a in what is now modern day Peru. The mit’a is considered an ancient version of mandatory state service. Before the arrival of the Spanish, the majority of Inca subjects performed their mit’a obligations in local agricultural settings near their homes.14 The original Inca version of the mit’a provided public goods and services, such as the maintenance of roads, irrigation and other agricultural systems.15

In contrast, the Spanish used the mit’a to service their vast silver mines. This created a subsidy for private mining interests and the Spanish Empire, which used the revenues to finance wars in Europe.16 Under Spanish rule, the use of the mit’a became increasingly abusive as miners were taxed and forced to purchase their own food while they participated in the mit’a. On account of these costs, the miners were persistently in debt, a burden they passed down to the next generation. This oppressive practice permitted the rapid expansion of silver mining by the Spanish who exploited tens of thousands of miners under the mit’a system. The system also severely impacted the Inca population by reducing the amount of healthy workers capable of producing food sources. This led to famine in the local communities and was further exacerbated by fleeing workers who evaded the Spanish mit’a.17 Little changed into the eighteenth century as the Spanish exploitation of the mit’a continued.18

The disparity between the miners and those who conquered them was stark. While the miners toiled away in slavery, the mine owners received wine and clothing from foreign merchants.19 It was not only the local inhabitants near these mines who were forced into these repressive conditions by the Spanish. For example, in the gold fields of the New Kingdom of Granada, Spanish mine owners relied on the importation of African slaves to form the bulk of their labour force.20 Thus, the Spanish Empire’s pursuit of precious metals was an example of a global human rights catastrophe centred in the Americas.

This practice of exporting slaves from Africa was also utilised for copper mining in the mountains of Cuba. Since the sixteenth century, the copper mining industry has continuously operated in Cuba and control has passed from the Spanish Crown, to private contractors, foreign companies and eventually to the socialist state. In 1670, the Spanish Crown confiscated a neglected mine, El Cobre, from a former contractor that failed to abide by the terms of its licence. In doing so, 270 slaves originally from Africa became the property of the Spanish Crown and the mines’ production level began to increase.21 In the 1830s, a British corporation took over the mine and continued to rely on African slave labour well into the nineteenth century.22

A similar history can be found in Brazil in which the Portuguese Crown began to exploit the colonised land for minerals in the early seventeenth century.23 It has been suggested that news of gold strikes in Brazil during the 1690s set off the first significant gold rush in Western history that was unparalleled until the gold rush in California 150 years later.24 As in the Spanish American Empire, the Portuguese Crown owned all subsurface rights but granted use and benefit to local miners in return for a concession payment.25 Soon after Brazilian independence was declared in 1822, the Constitution was amended to allow foreign investment into the nation.26 This produced a flood of British investment into Brazilian mining.27

By the nineteenth century, corporations became the predominant vehicle that British investors used to manage their Brazilian extractive operations. As one example, the Saint John d’el Rey Mining Company was formed in London in 1830. The first acquisition made by the company was a 25-year lease of a Brazilian gold mine. The stockholders purchased these rights from three British merchants and a German physician who obtained an imperial decree to the resources located at the mine in 1828.28 The company’s reliance on slave labour to operate the mine had some commercial complexities. For instance, the costs of purchasing healthy African slaves nearly tripled from the 1850s to the 1870s.29 Therefore, the company began to rely on rented slaves at a reduced cost. These slaves were often rented from failed mining ventures.30 The management of the Saint John d’el Rey Mining Company created an elaborate rating system to evaluate rented slaves based on age, health, demeanor and gender.31 Thus, slave labour was commoditised so that the company directors could ensure the mine’s operations were sufficiently profitable. This continued even after the British Parliament passed the Aberdeen Act of 1845, which prohibited British citizens from purchasing slaves.32 Subsequent to 1845, the company’s board of directors lobbied successfully to allow for the continued renting of slaves and to keep slaves purchas...