eBook - ePub

The Art and Practice of Costume Design

Melissa Merz, Melissa Merz

This is a test

- 294 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

The Art and Practice of Costume Design

Melissa Merz, Melissa Merz

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

In The Art and Practice of Costume Design, a panel of seven designers offer a new multi-sided look at the current state and practice of theatrical costume design. Beginning with an exploration of the role of a Costume Designer, the subsequent chapters analyse and explore the psychology of dress, the principles and elements of design, how to create costume renderings, and collaboration within the production. The book also takes a look at the costume shop and the role of the designer within it, and costume design careers within theatrical and fashion industries.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist The Art and Practice of Costume Design als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu The Art and Practice of Costume Design von Melissa Merz, Melissa Merz im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas & Teatro. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE MAGIC OF COSTUME DESIGN

Designing costumes can be a wonderful and magical experience, but it also requires hard work and dedication. The desire to please everyone in the process may be prevalent; the ability to do so may be more difficult. Designers must balance the needs of the director, actors, and costume shop without losing their creativity in the process.

In a perfect world, every fabric and trim would be available at a price the designer could afford. Knowing the world is not perfect, designers have to constantly look at what is available, what can be built, what should be rented, what has to be bought, and how to balance everything to create the best show possible. Decisions need to be made often and quickly. Any designer will say time is the rationale behind many decisions, as costumes could be worked on endlessly if time permitted. But productions include deadlines, such as opening dates, which can dictate certain decisions. The audience is hoping for the best show possible, and that means bringing all viable ideas together and compromising as needed in order to create a cohesive and effective design.

“It [costume design] requires the study of history, knowledge of the decorative arts, an examination of psychology. It’s also like painting in motion. A costume designer works with composition, value, and color as does any artist. She analyzes character and monitors behavior as does any social scientist. She identifies theme, plot, and style as does any literary analyst. Not claiming expertise in any of these fields, a costume designer enjoys juggling.”

Marcia Dixcy Jory1 from The Ingenue in White, p. 4

THE COSTUME DESIGNER

A costume designer must possess practical knowledge in a variety of areas, particularly pertaining to the history of clothing. Recognizing the way in which clothing and architecture worked together to create popular styles and movements throughout history is also valuable. Understanding the psychology of clothing, or the reason people wear what they wear, is essential for creating a cohesive design. Its study is both fascinating and valuable. A designer may not find it necessary to be an expert on all aspects of humanity, but continued study into the mannerisms, movements, culture, purpose, evolution, fabrics, construction, and social histories will be useful with different periods of dress. It is important to look at the rules of design while understanding that intuition also plays a part in the final outcome. Since costume design is an art, many of the same tenets apply; a designer knows about composition and balance and allowing imagination to influence creativity.

In addition to the abovementioned skills, one of the most important traits a costume designer can possess is openness and a willingness to change. A designer who feels what they have created on paper is the only choice will continually have problems. They must be willing to focus on the overall image the directors are trying to convey and take into account what the audience will see. They should be willing to work with other designers to understand their views of the play and how their art works within the needs of the production.

While designers cannot help but dream of the ultimate designs, most are faced with the hard realities of budgeting time and money. Almost anything can happen if you have unlimited resources, but few have that luxury. For example, the desire to find that perfect fabric is not always fulfilled. You may want wool made as it was in the 1700s, but instead, the wool blend at a local fabric store may be the only thing that will work within the constraints of your time and budget. Does it make the costume any less appropriate? No. It is important to remember this is a theatrical production. The goal is not to reproduce or create a piece that would fool a museum. At the same time, within the production itself, it might appear to be a work of art that makes the actor feel like they have walked out of a painting, which will delight and enchant the audience. Still, designers must balance what will be effective against cost and the availability of supplies.

Once designers know who has been cast in each role, they have to take into account the actors’ natural attributes and understand how to highlight them, not work against them. Different shapes and sizes of the actors’ bodies offer wonderful variation on stage. If an actor’s appearance differs from that which the designer had in mind, it may require an adjustment in the costume to accent the actor’s qualities. For example, if the designer envisioned a short, thin man in a role, but a large, tall man is cast, it could affect the shape, fit, and scale of detail on the clothing.

All of this costuming art does not happen without the help of those who build the costumes. This includes the dyers, who are chemists as well as artists, who give each fabric the perfect shade; the cutters, who begin with a sketch to develop the patterns; the stitchers, who sit for hours at a sewing machine to make everything just right; and those individuals who alter the ready-made garments. It includes all of the artists who contribute to the overall look, which may include wigs and makeup. Whether there is an entire team of people performing these jobs, or the designer is doing it all, the results can be truly magical.

Due to the number of people with whom designers closely work, there is often a need to leave their ego at home and engage their sense of humor. Being a designer means working with different personalities with different needs. Keeping a sense of humor about oneself and the work helps everyone enjoy the experience. Theatre production teams all want the same thing: a production that thrills all involved, including the audience. Most involved feel as though they have put everything into the production. While it may be true that actors feel the most exposed, the designers also feel exposed or vulnerable when it comes to the opinions concerning the overall quality of the production. It is chancy to put your art out there for others to see. Because of this, theatre practitioners can be tense and even insecure at times. Costume designers are no different. This is the time when both understanding and a sense of humor are needed the most. Designers must keep their wits about them, roll with the changes, overcome stress, and, hopefully, still enjoy themselves. If they can understand this and know that life does not revolve around such things as which buttons to use, for example, they have a greater chance of becoming truly great at what they do. Fine details are a valuable asset as long as the whole picture is kept in focus. Costume designers cannot think they or the costumes are more important than the other elements of the production.

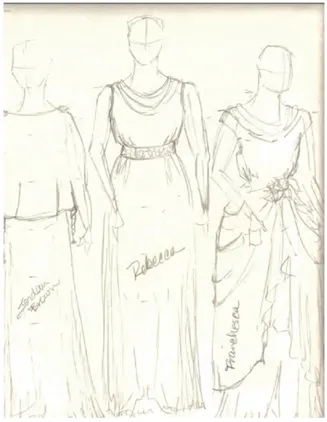

One of the greatest tools in any designer’s toolbox is the ability to draw. Whether by traditional means, or with the latest technology, the need to express ideas by drawing is a very important part of the dialogue with a production team. If you have sketches in a meeting with a director, it is important to be able to re-draw or draw over them as needed. The more complete the sketch, the better it will convey your ideas to the production team and the costume shop. The more a designer can draw with confidence, the more believable the drawing will be. Ultimately, while it is wonderful if the rendering is beautiful, the main purpose is to convey information. The more detailed a rendering, the more control the designer will have.

Not all productions require drawn renderings. If working on a production where the costumes will be completely bought or pulled from stock, it might be more effective to show pictures from several resources. If the opportunity is available, showing actual garments may be the most useful. But certainly photos of different garments are helpful as well. Probably the most popular way of expressing initial ideas is through a collage, creating a series of images from magazines, the internet, and even photos of stock costumes, that show a production team a series of ideas about how a character is conceived. The majority of images will probably be of clothing. Images expressing color ideas or even patterns can also be included.

Each designer decides how to arrange the images to best fit the circumstances. The most common way of arranging these images is by male/female, lead characters/chorus, or even each character positioned individually. These pictures can be arranged and overlapped in several different ways—whichever method is most effective in relaying ideas. One of the most recent methods is the use of paper dolls. This includes using a figure—found or drawn—with clothing added on top. Images of specific clothing can be used. Other clothing can be cut to shape from a print appropriate to the item. It can be an effective way to get specific ideas across to a director and the production team, especially when relaying more contemporary designs. (See Chapter 4 for more details on rendering).

HOW TO BEGIN

“What makes costume design so interesting to me is that rather than responding to a work of dramatic literature as a purely intellectual, critical exercise, a theatrical designer joins her own creative sensibility and artistic skill with the poetic genius of the playwright.”

Marcia Dixcy Jory1 from The Ingenue in White, p. 4

With any play, the process starts with reading the script, which provides inspiration and information. The written play is the basis for style, rhythm, and characterization. While reading it the first time, movement, images, and emotions should flow through the mind, without any particular reason. Logic, or a sense of correctness, is not important during the first reading. The emphasis should be on experiencing the play as it is written. It is difficult not to form an opinion about the play, concerning likes and dislikes. However, designers must be mindful not to allow their opinions to cloud their judgment in regards to what they have to do. Allow those opinions to form, then push them aside. Think about what the playwright is saying, the plot of the script, and how it all comes together. Absorb the story and encourage the imagination to flow. After the initial assessments and images are formed, some designers like to spend a moment writing down those thoughts or creating sketches which do not limit them to one area of design. These ideas and images may remain personal, or they can be shared with others in the production team. They may be the catalyst for an initial design or they may be held until further readings. The whole point is to have these notes available when or if they are needed.

What If There Isn’t a Script? What If It’s an Idea?

Not all productions begin with a script. With devised theatre, it may be a line, an object, or a movement. If that is the case, there is not a play to read before rehearsals or the more traditional design process begins. A theme or idea may be the catalyst for a production. A number of companies have been established that use the devised theatre technique: Blessed Unrest, The Ghost Road, Gecko, and Faulty Optic among others. More than with a traditional play, the process of using the devised theatre technique includes exploring ideas, some of which work, while others are abandoned. In the end, the final product may be completely different from what was started. Maybe the central theme is the only idea that survived from the first rehearsals. Costume designers should contribute to the experience whether they end up having little or a significant impact on the ...

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: What is Costume Design?

- Chapter 1 The Magic of Costume Design

- Chapter 2 Identifying Character Through Clothing

- Chapter 3 Costume & Character: The Elements and Principles of Design in the Creation of Sculptures in Motion

- Chapter 4 Costume Rendering

- Chapter 5 Costume Collaboration

- Chapter 6 In the Costume Shop

- Chapter 7 Costume Design Training: Creating in other Contexts

- Chapter 8 Show Business: No one Calls it “Show Art”

- Glossary

- Index

Zitierstile für The Art and Practice of Costume Design

APA 6 Citation

[author missing]. (2016). The Art and Practice of Costume Design (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/2192855/the-art-and-practice-of-costume-design-pdf (Original work published 2016)

Chicago Citation

[author missing]. (2016) 2016. The Art and Practice of Costume Design. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/2192855/the-art-and-practice-of-costume-design-pdf.

Harvard Citation

[author missing] (2016) The Art and Practice of Costume Design. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2192855/the-art-and-practice-of-costume-design-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

[author missing]. The Art and Practice of Costume Design. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2016. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.