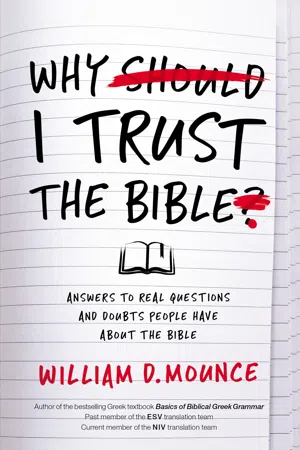

Why I Trust the Bible

Answers to Real Questions and Doubts People Have about the Bible

William D. Mounce

- 224 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

Why I Trust the Bible

Answers to Real Questions and Doubts People Have about the Bible

William D. Mounce

Über dieses Buch

A Clear Guide to Help Readers Understand Why They Can Trust the Bible

We are often told we can no longer assume that the Bible is trustworthy. From social media memes to popular scholarship, so many attacks have been launched on the believability of Scripture that many have serious questions about the Bible, such as:

- Did Jesus actually live?

- Did the biblical writers invent their message?

- How can we trust the gospels since they were written so long after Jesus lived?

- How can we believe a Bible that is full of internal contradictions with itself and external contradictions with science?

- Aren't the biblical manuscripts we have just copies of copies that are so corrupted they don't represent what the original authors wrote?

- Why should we believe the books that are in the Bible, since many good ones were left out, like the Gospel of Thomas?

- Why trust the Bible when there are so many contradictory translations of it?

If you find yourself unable to answer questions such as these, but wanting to, Why I Trust the Bible by eminent Bible scholar and translator William Mounce is for you. These questions and more are discussed and answered in a reasoned, definitive, and winsome way.

The truth is that the Bible is better attested and more defensible today than it ever has been. Questions about the Bible are perhaps the most significant challenge confronting Christian faith today, but they can be answered well and in a way which will lead to a deeper appreciation for the truth and ongoing relevance of the Bible.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Information

TEXTUAL CRITICISM

Challenge

Notes

Chapter 7

ARE THE GREEK TEXTS HOPELESSLY CORRUPT?

Nature and Significance of Textual Differences

Historical Process

Principles of Textual Criticism

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Abbreviations

- Preface

- The Historical Jesus

- Contradictions

- The Canon

- Textual Criticism

- Translations

- The Old Testament

- Conclusion: Why I Trust the Bible

- General Bibliography