![]()

1

James Lowell Gibbs Jr.

A Life of Educational Achievement and Service

DALLAS L. BROWNE

Family Background and Early Values

James Lowell Gibbs Jr. was born on June 13, 1931, in Syracuse, New York, to Huldah Dabney, a schoolteacher, and James Lowell Gibbs, executive director of the Paul Laurence Dunbar Community Center in Syracuse. Gibbs was a premature baby who had to fight to enter the world and has repeatedly fought and won since then on matters dear to him.

Gibbs’s family ancestry can be traced back to 1814 to his paternal great-grandfather, who was born in Florence, South Carolina. His parents grew up in Richmond, Virginia, where they experienced what a full black community was like, with its own institutions and possibilities. Jim’s parents made him aware early in life that the working-class community of Ithaca, New York, where he grew up was not the only kind of black community. Jim made summer visits to Richmond, where he witnessed thriving black institutions. His sister, Huldah, remembers traveling by train to Richmond; the passenger cars were integrated until the train reached Washington, DC, she recalls, but from DC to Richmond they had to travel in segregated Jim Crow passenger cars.

Jim and Huldah’s parents subscribed to the Afro-American and the Pittsburgh Courier, both of which were major African American newspapers; by reading them, his family was able to stay abreast of major issues facing black communities nationwide. As a boy he sold both papers to earn spending money. Throughout his life Jim remained deeply connected with the black community wherever he went.

Jim’s father attended Auburn High School in Richmond alongside Jim’s mother. Both earned high school diplomas; his mother was valedictorian of her class, while his father was an honor student. His father was the first in his family to earn a high school diploma, and his family was very proud of this fact, because at that point in history, earning a high school diploma was considered a great achievement in America. It took considerable determination, courage, and effort to get that far then; thus most African Americans who earned diplomas did so despite considerable resistance. During the slavery and post-slavery era, whites saw education and learning among blacks as a threat to their power, because blacks who could read and write had organized slave revolts.

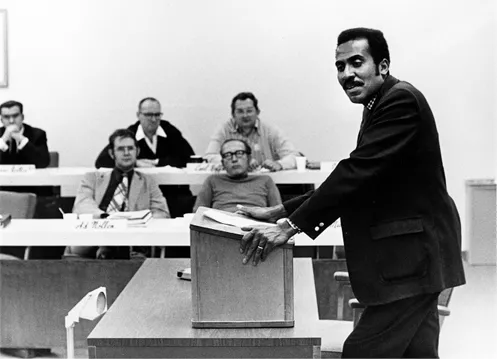

James Lowell Gibbs Jr.

Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections and University Archives. Stanford News Service / Leo Holub.

His father was a pillar of the black community since he served as director of the Ithaca Southside Community Center, which was the pride and focal point of the black community. He was accorded more respect than most social workers because he worked closely with white captains of industry, as well as leaders of the African American community, to place black workers in jobs. He was civic minded, and as head of the local chapter of the NAACP, he sought to peacefully advance the concerns of blacks for justice and equality.

Jim’s parents would later take college courses, but neither ever earned a college degree; this was not unusual for African Americans of their generation. Even today, it often takes African Americans who are the first in their family to complete a college degree eight or more years to finish a four-year course because they have to work to support themselves, have to perform military duties, or are forced to drop out to support a family. The same issues plague many white students but in lesser numbers. The huge gains in educational achievement in subsequent generations is staggering and demonstrates how far African Americans have come in a few generations, even though there is much further to go to reach parity with whites.

Jim’s mother, Huldah Hortense Gibbs, was an elementary schoolteacher before her marriage. After her family moved to Ithaca, she became very active in the community and in her church. She served as the president of Church Women of Ithaca, ran for the city alderman’s office but lost, and was appointed by the governor of New York to the board of visitors of the Elmira State Reformatory. She was very active in the Democratic Party and the local chapter of the NAACP. Both of Jim’s parents were excellent community service role models, which would shape his later involvement in civil rights and political activism. Jim was proud of both of his parents for being professionals who led their community; it made him feel special. Huldah says that they always felt themselves to be part of the local African American elite and were well aware of the privileges they enjoyed that few other African Americans did.

Early Education and Goals

Jim attended Henry St. John’s Elementary School, skipping second grade. He later attended Boynton Junior High School and Ithaca High School, where he excelled as a student.

Jim and his family lived on the third floor of the Southside Community Center. His family often invited HBCU professors to dinner when they came to visit or study at Cornell. Arthur Teele, then the chair of the Political Science Department at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University impressed Jim greatly. Throughout his life Jim maintained a friendship with Teele’s son. His parents also knew several black graduate students at Cornell and often invited them to Sunday dinners. One of these students was Fenton Sands, who earned a BS and PhD and went on to become one of the Tuskegee Airmen during World War II. Sands enjoyed a distinguished career as an agriculturalist. Later in life, Sands, who was teaching at Cuttington College in Liberia, welcomed Gibbs when he arrived there to do fieldwork for his PhD in anthropology. The environment in which Gibbs was raised made it clear to him even as a boy that black people could become professors who could shape and mold future generations of scholars.

Eslanda Robeson’s Influence on James Gibbs

Gibbs initially wanted to become a commercial artist or an architect, and his sister told me that he spent a lot of time making papier-mâché dolls for puppet shows that he performed for classmates. All of this changed when he read a book, written by Eslanda Goode Robeson, titled African Journey (1945). Eslanda studied anthropology under Bronislaw Malinowski and participated in his famous seminar at the London School of Economics. Among her seminar mates were colonial officers, as well as Allison Davis and Jomo Kenyatta (the first president of an independent Kenya). This book challenged white colonial rule over black Africa and was among the first voices to call for “Africa for the Africans.”

Eslanda Robeson and her husband, Paul, initially aspired to a conventional middle-class status. Paul earned a law degree from Columbia University and wanted a career as a lawyer, but someone discovered that he had a great voice, and this took his life in a direction that he never imagined. Eslanda was a chemist by training who studied anthropology to fill her time while Paul traveled internationally. You might say that she backed into anthropology. She found the views of her seminar mates offensive. These former colonial officials voiced negative views of Africans.

When Eslanda would try to stand up for Africans and argue that their minds were not primitive but rather they had been discriminated against and held back, they would say that she was naïve and had no experience among Africans. Eslanda was wealthy and asked Bronislaw Malinowski and Professor Issac Schapera, who held an appointment at Rhodes University in Grahamstown, South Africa, to introduce her to people throughout Africa so that she could see for herself what Africans were like on the continent. (Gibbs would later make use of Schapera’s work on Tswana traditional law when he collaborated with Stanford law professors to produce a book on comparative law.) Eslanda sought empirical knowledge of Africa. She traveled to Africa in 1929 but did not find time to publish her findings until 1945 (Ransby, Eslanda). This book was an attempt to defend the honor and innate ability of Africans. Unlike many books of its day, it did not characterize Africans as “savages” who were incapable of self-governance. Given that James Gibbs was brought up to see himself as a defender of the black quest for justice and equality, it is easy to understand the strong influence this book may have exerted on him. Perhaps anthropology would reveal the equality of all humans.

Growing up in the college town of Ithaca, New York, Gibbs came to think of professors as VIPs. He asked, “Why become a doctor when you could become a professor?” Cornell professors made up a large part of the local elite, and this made the idea of becoming a professor attractive to him.

Gibbs states that in the 1940s Ithaca had one junior high school and one high school. This meant that students were exposed to people their own age of all socioeconomic backgrounds and races. He had classmates who modeled good student behavior that classmates could emulate. Good students tend to participate in a wide variety of extracurricular activities. College towns value excellent education, and even though Ithaca did not have its first black teacher until long after Jim graduated from high school, he had many teachers who encouraged him. All successful students need a supportive environment to thrive.

Cornell University

Gibbs graduated from Cornell University, where he was elected senior class president. He was the first African American man from Ithaca to earn a degree from Cornell University. His Cornell BA in sociology and anthropology was awarded in 1952. Jim loved Sociology 101 at Cornell because he learned about social stratification, which fascinated him. He enjoyed reading W. Lloyd Warner’s books because he could see evidence of stratification all around him. This course explained why “whoever was up was up and whoever was down was down,” in Jim’s words. It explained why people behaved the way that they did.

Jim secured research opportunities each summer while still an undergraduate. He worked as a research assistant for Robin Williams, John Dean, and Edward Suchman for their book Strangers Next Door (1964), which examines the desegregation of American ethnic enclaves. Robert Johnson, the son of Charles Johnson, who was a sociologist and president of Fisk University, was one of the graduate students who worked with Jim on this project and mentored him in research methodology, as well as the ins and outs of academia.

While an undergraduate at Cornell, Jim participated in many extracurricular activities. He joined Watermargin, the first interracial fraternity at a major American college, and he was invited to join Quill and Dagger, an honor society for outstanding students who have good grades and are active in community service. He also worked part time at various jobs on campus to supplement his scholarship.

The Harvard Years

During his first year at Harvard he enrolled in the new multidisciplinary social relations degree program. In 1946 Harvard College decided to create an experiment in social science education known as the Department of Social Relations. It drew faculty from three departments that continued to exist alongside this interdisciplinary department. The Social Relations Department insisted that first-year graduate students take core courses in anthropology, sociology, and psychology so that their training would be cross-disciplinary; after that, students would major in one of these fields, and that department would award their degrees. Thus, Gibbs took core courses in all fields as well as in the Department of Anthropology. Coursework included tutorials and comprehensive examinations.

Gibbs took a class with Ernest Hooton at the Peabody Museum, and he was surprised when, on the first day of class, Hooton announced, “I have not seen one of you since Allison Davis took courses with me!” Gibbs never met Allison Davis, but he was aware of him. He feels that he was a beneficiary of Davis’s sterling performance as a student and professor and that people like Davis made it easier for him to pursue his dreams by paving the way for him. Harvard’s interdisciplinary approach is reflected in the fact that both Gibbs and Davis dabbled in psychology and published in this area, although neither was a psychologist by training. This eclectic approach is also seen in Gibbs’s writing on law, although unlike Sally Falk Moore or John Comaroff, he did not hold a degree in law. Again, this reflects Harvard’s interdisciplinary approach to anthropology.

Talcott Parsons taught the sociology course. Parson’s daughter Ann sat next to Jim in class, and they became friends. Later that year Ann invited Jim home for dinner, where he got to know the great professor better. During that same year Gibbs was informed that he had been awarded a Rotary Fellowship that he could use anywhere in the world to further his studies. Jim consulted with Parsons about universities, and Parsons suggested that Jim consider Cambridge because Parsons had an invitation from Meyers Fortes, who chaired the Anthropology Department at Cambridge. Fortes convinced Gibbs to spend a year at Cambridge so he could take courses from and become familiar with Great Britain’s leading Africanist anthropologists.

Under the Cambridge University system students had to enroll in a particular college. Not being familiar with the college system, Gibbs asked Fortes for advice and Fortes recommended Emmanuel College. Among the many distinguished alumni of this college was John Harvard, after whom Harvard University is named. Affiliating himself with this college was an appropriate way to honor John Harvard.

Gibbs enrolled in Emmanuel College but he had to live off campus because Cambridge had few American students in those days and their housing was off campus. Fortes felt bad about this, so he arranged for Gibbs to live for the year on campus in the Anthropology Department’s guest housing for visiting scholars.

At Harvard, Jim was the first black resident tutor at Adams House, and he also served as a teaching fellow in social relations between 1954 and 1956. Jim believes that his Cambridge experience helped him to secure a tutoring position at Harvard because English universities have residential colleges where students work closely with tutors.

One of the students living at Adams House was Paul Riesman, the son of renowned sociologist David Riesman. David Riesman became a mentor to young James Gibbs. Throughout his life Gibbs has enjoyed phenomenal good luck. It seems that he met many influential social scientists early in his education and career who befriended and mentored him.

While taking graduate classes at Harvard he met his wife, Jewelle Taylor, an undergraduate at Radcliffe College, who was the only African American woman in her class. She barely noticed Jim, so he set up a blind date with her and later took a class in the sociology of law with her. They courted for a year and then married in August 1956. She accompanied Jim while he conducted fieldwork among the Kpelle of Liberia and conducted her own studies of Kpelle women while Jim studied Kpelle men and their legal system. Jewelle Taylor Gibbs is a scholar in her own right; she earned a doctorate in psychology and then joined the faculty of the School of Social Welfare at the University of California at Berkeley. She ultimately became the first African American professor to be appointed to an endowed chair in the ten-campus University of California system. She retired from there in 2000 as the Zellerbach Family Fund Professor of Social Policy, Community Change, and Practice Emeritus. They have two sons; their older son, Geoffrey Taylor Gibbs, is a lawyer who lives in Alameda, California, with his Brazilian wife, Cristina, and their two young children. Their younger son, Lowell Dabney Gibbs, is a financial adviser who lives in Sonoma, California.

Gibbs believes that the Cambridge model of residential education made him a most effective tutor at Harvard and in ma...