![]()

1

Beginnings

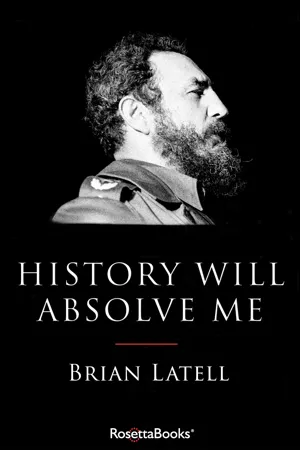

“Condemn me; it does not matter: history will absolve me.” Nothing else the beardless Fidel Castro said at his trial that autumn day in 1953 was remembered for long. But those words he defiantly shouted at his accusers in a provincial Cuban courtroom have reverberated ever since, forever defining the essence of his remorseless revolutionary creed.

“History will absolve me” endures as the most memorable phrase he ever uttered. He was on trial for multiple capital crimes, yet confident he would be exonerated, sure that the violence he unleashed had been just and necessary. Later, during his long run in power, it was always the same. That implacable belief in himself and the rightness of everything he did in the name of revolution never wavered. For decades, his most appreciative followers in Cuba and far beyond invariably agreed. To them, he was a heroic and benign leader, a righteous David pitted against the cruel American Goliath.

In the early years of Fidel’s struggle to win power, “history will absolve me” was the propaganda refrain most often used to rally popular support. It burnished Fidel’s revolutionary credentials, endowing his cause with a noble inevitability. What he had done was honorable and necessary. Nothing he subsequently said has resonated with such force. Those words perfectly encapsulated his warrior ethic.

He stood accused in Santiago, Cuba’s second city, charged with masterminding a burst of revolutionary mayhem a few months earlier. At dawn on Sunday, July 26, 1953, he led a group of followers in a surprise assault on the Moncada garrison in Santiago. There was no denying that he organized and led the attack on one of the largest military bases on the island or that his intent was to overthrow the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista by sparking a popular revolt. Though he failed in every respect, Fidel was proud of what he did, pleased that his exploits were front-page news. With this one explosion of violence, he had made his mark. He was sure that history would approve.

Speaking in his own defense—he was a University of Havana–trained lawyer—he admitted to no regrets about the large loss of life on both sides. He later said that eighty of the young men he recruited had perished. They were the first of his many martyrs, and that too had been part of the plan.

Sharing that plan with a favorite law school professor shortly before the attack, Fidel was cautioned that the chances of success were slight. Characteristically, his response was both cold-blooded and visionary: “There is no turning back,” he said. “We need a rallying point, and if necessary we shall provide martyrs.” By throwing those poorly armed and gullible young men into suicidal battle against a much greater force, he exhibited the incorrigible qualities that would always mark his leadership.

As I came to better understand Fidel’s extraordinary complexity, I read the recollections of one of his contemporaries, an old Havana friend. Max Lesnick lives in Miami but still supports the revolution. Fidel, he said, “had precise plans for creating his own place in history. He was always imbued with the conviction that he had to fulfill some transcendental mission, and he was violent but also always calculating.” He was “obsessed with conquering power, by whatever means.” Lesnick believed that the young Fidel’s quest for a historic destiny would likely produce either greatness or martyrdom.

Epic dreaming began during Fidel’s painful childhood. A Jesuit priest who befriended him at Belen, the elite Havana prep school, now relocated in Miami, recalled that Fidel “often spoke of not really having a family. He suffered considerably as a child. …I counseled him about trauma.” Fidel’s mother, Lina Ruz, was an uneducated teenage maid in the ramshackle house of his father, Ángel Castro, an illiterate, uncultured Spanish immigrant. Ángel and Lina began having children, seven altogether, even as at first he remained married to another woman. He lived with his wife and their two children in Birán, a hardscrabble hamlet in eastern Cuba.

Fidel was the third in Lina’s illegitimate brood. Official records indicate that he was born on August 13, 1926. In fact, Lina and three of Fidel’s sisters admitted that he was actually born exactly one year later. Asked by an American reporter about the discrepancy, Fidel seemed to acknowledge the truth of his age. “I take the less favorable date,” he said. Apparently wanting to enter Belen when he was a year too young, he persuaded Ángel to bribe a local official and purchase a false birth certificate.1

But earlier, he had no standing in Ángel’s house. Banished as an infant to a nearby shanty, he was later exiled to the dark and distant foster home of a destitute Haitian immigrant family. He was isolated, hungry, and emaciated there. There was nothing to do, no escape or stimulation, and… no visitors from Birán. It was devastating. He had been rejected by the indifferent father he knew only from a distance, and abandoned by his mother. Fidel’s Jesuit teacher understood that his illegitimacy was a gnawing embarrassment, a formidable obstacle to his grand aspirations.

Others may have despaired, been ground down by what he suffered, but the young Fidel was steeled by the adversity, learning to manage under duress and rebound psychologically. Realizing that passivity would gain him nothing but more misery, he often prevailed by seizing the initiative and going on the offensive. He later told interviewers how he had learned when young to resort to extreme, even theatrical measures when his plight was dire.

All his life, he demonstrated an extraordinary intelligence. Unquestionably, he would have ranked in the highest percentiles on any standardized test of cognitive ability, a Cuban Mensa. One of his high school classmates described Fidel’s photographic memory to me as “pathological.” When in power, he employed this gift with aplomb. In speeches, he delighted in rattling off streams of mind-numbing statistics and obscure details about subjects as diverse as animal husbandry and sugarcane blights. He often impressed foreign visitors by regaling them with his knowledge of obscure chapters in their country’s history.

Psychologically, Fidel was even more unusual. He never felt a need for mentors, role models, or confidants, once admitting that he had few friends. Even as a youth he was remarkably autonomous and self-assured. “I can’t recall ever having had doubts or lack of confidence,” he told interviewers. Branded in him was the fear that to be dependent on others would make him weak and vulnerable again.

Ángel came to recognize these exceptional qualities in his third son, seeing much of himself in the relentless, indomitable boy. The old man gradually accepted and embraced the audacious child, finally legitimizing him as his son when Fidel was about seventeen.

From these origins, Fidel’s adult psychological makeup coalesced and remained surprisingly constant for the rest of his life. Years of fending for himself made him narcissistic and self-absorbed. In power, no one else was allowed to share the limelight, and knowing that, some, like the celebrated Che Guevara, voluntarily exited the Cuban stage. With adult successes, Fidel’s childhood melodramas flowered into grandiosity. It was impossible for him to empathize over the plight of others. He had no ability to grieve or bond in truly sharing relationships with anyone.

Unable to acknowledge serious errors of judgment, he rarely expressed regrets or contrition. It was not that he actually professed to be infallible, rather that he could not bear critics or doubters. They might betray him. Yet, as unusual as the workings of Fidel’s mind and psyche were, I am aware of no evidence that he ever lost touch with reality or acted irrationally. None of his biographers, family, or associates have said that he suffered from bouts of depression or psychosis. His brand of sanity was spectacularly—perhaps sociopathically—unique.

While at the University of Havana in the late 1940s, he emerged as a notorious gunslinger. A little over six feet tall, burly, and strong, he was feared for his imposing physicality and rough country manner. Almost always armed and cocked for action, he was one of the city’s most menacing young gangsters.

Implicated as the hit man in two murders, including one where witnesses observed him near the scene of the crime, he somehow evaded prosecution. There is no uncertainty about a third case, a cold-blooded assassination attempt in December 1946. According to reliable eyewitness testimony, Fidel severely wounded a popular young student rival by shooting him in the back in an unprovoked ambush. No charges were filed against him that time either.

He could operate with merciless sangfroid. That was apparent again a year later, when he joined young Cubans and Dominicans in an effort to overthrow the dictator of the Dominican Republic. They gathered on a cay off the northern Cuban coast and trained on high-caliber weapons. Juan Bosch, a future Dominican president, was there as nominal leader of the expedition. Years later he told Georgie Anne Geyer, one of Fidel’s biographers, about the heartless young Cuban he met there.

Another trainee shot himself accidentally, Bosch said. “His whole stomach was hanging out.” Fidel witnessed the accident, and Bosch said that he scrutinized his reactions. Fidel’s gaze was fixed on the face of the dying man, and he kept looking: very serious, showing nothing. “I will always remember that Fidel was very cold and serene. The fact was that he made no demonstration of emotion; and he continues to be that way.”2

He was an anarchist in the late 1940s, bereft of any uplifting cause. No inspiring ideology had yet imbued him. The imperative to win fame and glory, somehow to wield political power, was paramount. But toward what end? What purposes other than his own glorification propelled him? He never bothered to say in those days who else might benefit if he were to gain power, or what enduring causes he might champion. The poor and downtrodden were not yet mentioned as the intended beneficiaries of his efforts. It would be several more years before he began to rail against the injustices and exploitation he saw in Cuban society.

Meanwhile, right-wing regimes and leaders attracted him, although he could never admit it. At Belen, he was taught to admire the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco. One of his Spanish Jesuit teachers told me that, as a teenager, Fidel “was more of a Francoist than I was.” At the university, he studied Hitler’s Mein Kampf. It could have been a coincidence that Fidel’s cry that “history will absolve me” nearly duplicated the closing words of Hitler’s speech at his trial in 1923 after the Beer Hall Putsch. But, consciously or not, Fidel most likely appropriated the phrase.

He had no interest in democratic leaders, even the most iconic ones of his youth. He was aware of how Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill were leading free peoples against the tyrannies of the Axis powers. They were the most prominent and inspirational figures on the world stage, and exceptional orators. Always the ardent student of leadership dynamics, Fidel ought to have been interested in their outstanding qualities, but he paid them no attention. Their powers were constrained by institutional checks and balances and the ballot box. His heroes were steely men of action, able to impose their will.

There was one area of settled belief that the young Fidel held dear before the Moncada attack. He was, in his marrow, anti-American. Like his nationalist contemporaries, he was convinced that the United States had been exploiting Cuba since its intervention in the Spanish-American War at the end of the nineteenth century. Cuba’s independence, he knew, had been a farce during its first three decades after the split from Spain.

The Americans demanded the right, enshrined in the Cuban constitution, to intervene by force, using almost any pretext. Humiliating military occupations followed. American ambassadors were often more powerful than Cuban presidents and dictated policies devised in Washington or at the headquarters of American corporations. After the war with Spain, the United States retained the deep harbor and surrounding territory at Guantánamo in eastern Cuba, building a vast naval base. It was still under American control when Fidel died. Cuba, he concluded from knowing its history, was an innocent victim, just as he had been as a boy.

![]()

2

‘My True Destiny’

Fidel was in the grip of these nationalistic passions when he traveled to Bogotá, the Colombian capital, in April 1948. He went determined to make trouble for the United States, not to participate in a revolutionary upheaval. It developed that he did both. American Secretary of State George Marshall and the foreign ministers of the Latin American countries were meeting in Bogotá’s Teatro de Colón.

The charter of the Organization of American States was concluded there, but not before Fidel mounted a vehement protest. With other Cubans, he gained access to the Colón balcony, where, shouting, they managed to scatter anti-American leaflets onto the conference floor below. The message was that the United States was again ravaging benighted Latin Americans.

The incident passed without much notice, but soon Fidel threw himself into the most savage urban violence in modern Latin American history, the bogotazo. A popular presidential candidate had been assassinated and the large city high in the Andes burst into appalling waves of violence. By his own accounts, Fidel reveled in it, seizing arms from hapless policemen, joining local revolutionaries marauding in the streets, and firing on Colombian police and military units trying to restore order. He made it clear that he did not hesitate to join in the bloodletting.

His decision to stay and fight rather than scramble for safety reflected more than anything his gangster instincts. Naturally, he put a better face on it, justifying his actions. They were “in accord with my moral principles,” he would say. He acted with “dignity and honor… incredible selflessness.”

It was during the second day of fighting that, by his own accounts, he had perhaps the most important epiphany of his long career. His decision to participate in the violence suddenly acquired larger meaning. Recalling those events, he said he had fought on the side of the masses and realized in the fog of battle that he “was overcome with internationalist sentiment. …These people are oppressed and exploited. …I may die here but I am staying.” He was not yet twenty-one years old.

Even allowing for post facto bravado, this was the warrior and advocate for the downtrodden emerging in Fidel. Marxist doctrine, however incipient, was beginning to possess him. He remembered being “filled with revolutionary fervor, trying to get as many people as possible to join the revolutionary movement.” In the retelling, it is clear that he had assumed a leadership role in this, his first foreign adventure. Now he had a cause, an obligation larger than himself. He might even be able to put his unsavory gangster reputation behind him.

Fidel’s ideological blank slate was now glowing vividly red. He concluded he had seen a proletarian uprising in action and later made clear how impressed he had been that “an oppressed people could erupt” that way. The raw material of this ideological awakening had been present since his youth, when he learned to resent the Cuban upper classes, their condescension, privileges, and country club poses. Moreover, anti-imperialist rage and his understanding of Cuban history converged naturally with Marxist doctrine.

Back in Havana, he began to frequent the communist party bookstore, studied Marxist tracts, tutored his younger brother Raúl in the intricacies of Marxist-Leninist doctrine, and associated more regularly with communists. His Marxist beliefs would intensify during the ensuing years, and were compelling by the time of the Moncada assault, as Fidel has admitted. They remained secret, however. Fidel knew he could never win power as a Marxist or communist sympathizer. Instead, he delegated to Raúl the task of maintaining ties with leading Cuban communists as his surrogate.

It was the bogotazo that loomed largest in his strategic thinking. Bogotá became the model for Moncada five years later, and also for one of the strangest incidents in Fidel’s early career. After completing law school, he married, had a son, and affiliated with Eduardo Chibás, a promising progressive politician. Chibás actually had no use for Fidel, whom he considered “an unprincipled gangster.” But Fidel was present in August 1951 when the unstable older man shot himself while speaking during a radio broadcast. Cubans poured into the streets, expressing grief and horror. Reminded of the bogotazo, Fidel saw an opportunity, the chance to win power as an insurgent.

At the funeral, after delivering one of the eulogies, he approached one of Chibás’s top associates. “Where would the body be taken after the ceremony?”

“To the cemetery.”

Instead, Fidel demanded that it be carried processionally through the streets of Old Havana, ultimately to the presidential palace. He hoped the mourning masses of Cubans would spontaneously rebel.

“Why the palace?” he was asked.

“So we can seize power.”

It was thought to be madness, and he was ignored. Unlike some of his other bizarre escapades, Fidel reminisced positively about this one in a meeting in 1967 with Latin American journalists. He told them that he was proud of what he had hoped to accomplish with Chibás’s corpse that day. He remembered saying to others at the funeral: “Let’s carry the body to the palace, and there the people will topple the government. In one hour the revolution will have triumphed.”3

He conceived of the Moncada attack with the same mistaken logic. A proletarian, Bolshevik-style revolution led by mobilized workers was never his plan. It was the Bogotá experience that would be his model. The attack on the garrison would spark a popular upheaval against the dictatorship, bringing enflamed masses into the streets. Cubans would be horrified, he thought, repulsed by the savagery inflicted on his small band of idealistic followers. The regime would totter and fall. And if he failed, and survived, he would in an instant become the most formidable opponent of the dictator.

The attack produced many brave young martyrs for the revolution he was igniting. The names and legends of some of them resounded through the years of Fidel’s reign as early heroes of the cause. Many of those expendable young men were felled within the sturdy wa...