![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Changing Face of Ireland 1830-1880

The story of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century female emigration from Ireland begins in the half century before 1880. In the course of those fifty years, the country was in a state of flux, as overpopulation and periodic famine forced people to alter their way of life. Between 1830 and 1880, depopulation replaced overpopulation, and land consolidation and market agriculture replaced land subdivision and subsistence tillage, first in the north and the east, then in the south, and, finally, in the west. Despite these changes, in 1880 Ireland still depended on population decline to maintain an economy based on agriculture rather than industry. Emigration was responsible for much of this decline.

The changing demographic and economic conditions in Ireland during the course of the nineteenth century reflect the incomplete modernization of this British colony on the periphery of western Europe. Like its counterparts in the region, Ireland underwent an agricultural revolution in the eighteenth century when the potato was introduced as the subsistence crop of the island. By the early nineteenth century, although poverty was ubiquitous, the Irish were taller and heavier than their counterparts elsewhere in western Europe.1

Contemporaries remarked on their robust health, and historians have noted that the average Irish person, male or female, although confined to a potato diet, was extremely well nourished.2 “Let [the] ignorant . . . who say that potatoes and milk is not nourishing food, look at the children, generally in rags, but with every appearance and reality of ruddy health,” admonished one such informant touring Ireland in the early nineteenth century, “. . . [or] let them attend a football or hurling match, and see the superiority of potatoes and milk over . . . cheese and . . . beer—the young men performing feats of activity that would astonish a bread-and-cheese Englishman.”3

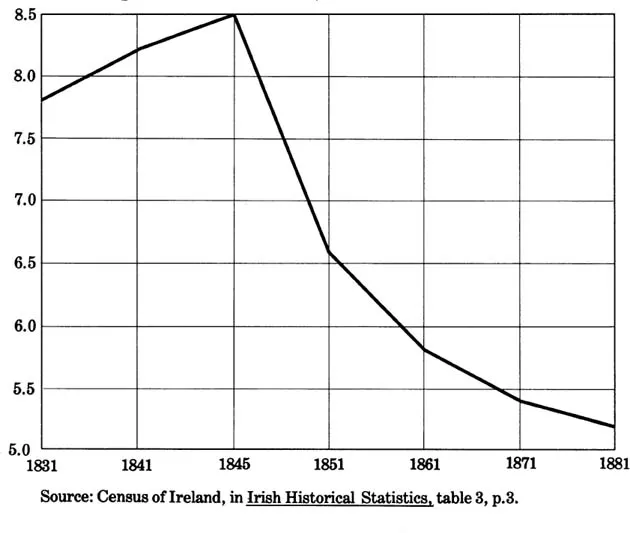

Population of Ireland, in Millions, 1831-1881

As a result of the healthful spread of potato cultivation after 1750, the Irish population increased at the highest rate in the British Isles, doubling from 4.4 million to 8.5 million between 1788 and 1845.4 After 1850, however, while the population elsewhere in western Europe continued growing, that of Ireland fell. By 1881 fewer people lived in the country than had in 1831.

Throughout western Europe, the population increases that began in the eighteenth century contributed to subsequent revolutions in agriculture, industry, and political organization. These changes, in turn, provided new means of support and accommodation for continuing population growth. In England, the agricultural revolution and subsequent population increase were followed by widespread changes in the economy. By the early nineteenth century, as England’s population began to rise at an unprecedented rate, industrialization absorbed this new human surplus. Little such economic development took place in Ireland, however, where the economy remained primarily agricultural and preindustrial.

Since Britain needed a market, not competition, for its burgeoning industries, its polices favored British enterprise rather than Irish. In addition, Ireland lacked some of the natural resources, the capital, and the entrepreneurial class needed for an industrial revolution. As a result, Irish agricultural, industrial, and political systems remained static despite dramatic demographic change.5 Without new economic resources to support the population increase, ever larger numbers of Irish faced a future of diminishing economic returns. Nevertheless, although contemporaries remarked on the widespread poverty of the Irish in the first half of the nineteenth century, as long as potatoes could be grown, population increase could be sustained. By the turn of the nineteenth century, Malthusian restraints on population growth in Ireland had disappeared.

These changes affected women in two major ways. First, most could marry and reproduce because potato cultivation allowed the establishment of new households in the subsistence economy. Second, because women held an important demographic and economic position in the labor-intensive economy of pre-Famine Ireland, they exercised a high degree of autonomy over their choice of when and whom to marry. As coproducers within the subsistence family economy, wives enjoyed a high status in rural Irish life.

After 1830, and especially after the devastating famine of the late 1840s, however, unchecked population growth and reliance on subsistence potato cultivation had mostly disappeared in the north and the east. The Famine was only a partial check to the demographic and economic patterns that had emerged after 1780, nonetheless. Although the Famine marked the end to overall population growth, patterns of early and universal marriage and reliance on subsistence tillage persisted among the much depleted laboring class, especially in the west and southwest, into the 1880s. High marital fertility also remained uncurbed among all population groups throughout the country.

Consequently, although the trauma of the Famine signaled the end of population increase in most areas of Ireland, other factors also contributed to the falling population levels after 1845. Since industrialization and land redistribution did not occur after the Famine, the Irish economy remained precariously perched on an archaic agricultural system. As a result, the rural majority soon demonstrated new demographic and economic behaviors. These new ways of life lowered the birthrate by delaying and restricting marriage, and reduced the number of people who could be supported by agriculture by changing the patterns of land use. Although Ireland eventually recovered from the worst ravages of overpopulation and mass starvation, renewed economic well-being came about only at the price of continuing depopulation and persistent emigration. As a result, increasing numbers of Irish women lost their reproductive as well as their productive roles in the third quarter of the nineteenth century.

The mass migration of women from Ireland in the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, therefore, reflected the simultaneous impact of the new demographic and economic patterns of post-Famine Ireland and the loss of the older but equally innovative patterns of Irish female life that had appeared in the late eighteenth century.

Changing marriage patterns in the half century before 1830 had a direct impact on population levels in those years. Beginning in the late eighteenth century, as the population rose with the spread of potato cultivation, most Irish men and women conformed to the European custom of marrying in their midtwenties.6 As one early nineteenth-century observer wrote, “An unmarried man . . . or a woman . . . is rarely to be met in the country parts.”7 Although the average age of marriage partners slowly increased after 1830, especially among land-holding tenant farmers, more Irish married and at younger ages before the Famine than they ever would again.

The decade following 1841 saw a rapid rise in the age at which most Irish would marry as economic disaster forced agricultural laborers to adopt the marital behavior of the better-off farming classes in order to survive. This trend continued throughout the late nineteenth century, and into the twentieth. By the 1880s the Irish married at the latest ages in Europe, over age thirty-four for men and over age twenty-nine for women.8

The marriage rate decreased as the marriage age increased. While at least three quarters of the Irish married before the Famine, by 1881 only one-third of their descendants were husbands or wives.9 Although the west was the last region to abandon pre-Famine demographic and economic behavior, by the 1870s marriage rates had decreased even there. For instance, while slightly more than ten marriages for each one thousand in the population of Knockainy Parish in County Limerick took place in 1840, fewer than half that number occurred in the parish in 1880.10

Changing marriage patterns in turn affected population levels. Since most women married at relatively young ages before the Famine, and because fertility rises with the length of marriage if birth control is not used, population increase among the mostly Catholic agricultural majority was inevitable. Although population statistics are unreliable before 1851, one trustworthy estimate places the birthrate at 33-40 per 1,000 in the population in 1841, the highest rate in the British Isles.11 Another indication of the high rates of population increase in pre-Famine Ireland is the high number of people living in the average Irish household. Though households were smaller among the poorer laborers than among the richer farmers, who often kept servants, the average pre-Famine Irish household, which usually contained a nuclear family, held five or six individuals, larger by one than its English counterpart. In the west, the region with the highest birth rate before the Famine, six or more individuals lived together in each typical household.12

After the Famine, the trend toward delayed and restricted marriage played an equally important role in the rapid and persistent decline in population. As marriage rates fell and as the age of marriage rose in the half century after 1830, fewer and fewer children were born over time. In 1864, the first year of the civil registration of births, 136,414 children were born. In 1880 only 128,086 births were recorded. By that year the birthrate had fallen to 24.7 for each 1,000 in the population.13

Once again the birthrates in Knockainy Parish, like those in Inishkillane Parish in County Clare, mirrored the countrywide pattern. In Knockainy, 37.3 births per 1,000 in the population occurred in 1830. By 1880 only 22 births per 1,000 in the population were entered into parish records. In 1843, 209 baptisms were performed in Inishkillane. By 1893 only 63 took place. Although marital fertility remained stable throughout the period, the low numbers of marriages in these parishes offset any potential population growth.14

Throughout the half century after 1830, changing population levels reflected the economic well-being of the Irish. As the population rose in the first half of the nineteenth century, the standard of living worsened. Conversely, as the population fell after 1845, the lives of the still agricultural population gradually improved. Confined to a finite amount of land, the Irish limited their numbers to promote economic recovery. By the late nineteenth century, population growth and subsistence tillage had ended almost everywhere in Ireland. These changes, in turn, would have a dramatic impact on the position of women in rural Ireland, as we shall see.

“Nothing can be more extreme than the poverty of the peasant,” exclaimed one traveler in Ireland in 1844,15 echoing the general view of his contemporaries that Ireland on the eve of the Famine was one of Europe’s most undeveloped areas. Irish agriculture and manufacturing had not always been on the brink of disaster, however. At the turn of the century, few Irish had lived at the subsistence level. Rents were paid in cash earned from domestic textile production, dairying, and poultry and egg sales—activities dominated by women. But the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 and the rescission of the laws protecting Irish manufacturing in the late 1820s allowed British goods to flood Irish markets, causing a fall in demand for both Irish products and labor.16 Furthermore, as population growth outstripped that of available resources, Irish home manufacturing simultaneously succumbed to mechanized British competition. As supplementary sources of cash income disappeared, more and more Irish were forced to depend on subsistence agriculture alone for their survival.

The greatest population growth before the Famine was recorded in areas least able to support it. While the total population in Ireland rose by 20 percent between 1821 and 1841, the population of the west, the region hardest hit by agricultural depression and the contraction of cottage industry, increased by 30 percent in the same two decades. In areas of Sligo, Kerry, and Leitrim, population increases of 40 percent occurred between 1821 and 1841.17 Moreover, the proportion of landless laborers and their families increased in the overall population in those years. In 1821 only between one-quarter and one-third of the population had been subsistence laborers and their families. By 1841 over one-half of all adult males lived on the subsistence level, and over 40 percent of the remaining population were dependents under age fifteen or over age sixty-five.18 The observation that “the only solace these miserable mortals have . . . is in matrimony; accordingly, they all marry young,”19 made in the late eighteenth century, continued to describe the marital behavior of the poorest groups among the Irish well into the nineteenth century.

As the number of people dependent on subsistence potato cultivation climbed, the fragmentation of land into ever smaller holdings kept pace. Since each child in a family was given part of his or her parents’ holding upon marriage, the average size of land holdings decreased with each new and larger generation. By 1841 over 80 percent of all land holdings in Ireland covered less than fifteen acres and fully 45 percent of all tenant-held farms averaged less than five acres in size. The number of holdings smaller than one acre also increased, especially in the overpopulated west. For instance, in 1841, on the Gweedore Estate in Donegal, more than twenty-six people lived on a land subdivision only one-half acre in size.20 On the eve of the Famine, over four-fifths of the Irish subsisted on densely populated, ...