![]()

PART ONE

Forming Energies

![]()

ROUTES/ROOTS/RAÍCES I

Recuerdos familiares [Family Memories]

I COME FROM ISLAND PEOPLES with Puerto Rican, Spanish, and Irish roots. At various times and in various places, my ancestors have contributed to and suffered the cruelties of colonialism and empire. In this first “Routes/Roots/Raíces” reflection, I piece together fragments of various memories, passed down in the form of intergenerational stories, and an “official” family history, contained in a self-published book written by one of my family members.1 Together, these materials constitute familial, migratory, technological, corporeal, and other energies shaped by powerful systems and relations that, while personal, also relate profoundly to the broader histories and conversations animating Energy Islands.

I vividly recall the last time I saw my grandmother’s sister, Consuelo, or “Titi Consi,” as I called her. On the way up to my great aunt’s apartment, I shared the elevator with a couple who just had purchased two Coleman camping gas tanks to restock their cooking fuel supply. More than two months after Hurricane María, the large apartment complex still was running on generators. I read in Claridad that the local government did not prepare residents for the health consequences of using emergency generators for several hours at a time. Journalists reported house fires and cases of carbon monoxide poisoning across Puerto Rico. When I arrived at the eleventh floor, Confesora, Titi Consi’s Dominican care provider, opened the door to my great aunt’s apartment and warmly guided me to where my relative was lying immobile on her narrow twin bed. Well into her nineties and recently having survived Hurricane María, Titi Consi’s frail body and facial features signaled the end was near. Like many Puerto Ricans, she was born on Puerto Rico’s largest island and migrated to the United States in early adulthood. She later returned to the archipelago to spend her final years, passing shortly after my November 2017 visit. Across the years and miles, Titi Consi and I had been dedicated pen pals, writing regularly to each other during my youth. As a child and teenager, I loved receiving her letters and feeling the connection they created between us. Though Titi Consi’s experiences and my own in the United States and Puerto Rico were very different, they both were influenced by intergenerational relationships, stories, and their consequences.

FIGURE 3. Titi Consi and me. Hato Rey, Puerto Rico, July 2014. Author photo.

“La gran familia puertorriqueña” [The great Puerto Rican family] popular narrative uncritically features three raíces contributing to Puerto Rican heritage: Indigenous Taíno, African, and Spanish. Underlying the story of these supposedly pleasantly interwoven roots is hispanofilia, which prefers all things and people associated with the Iberian Peninsula via strong affective connections.2 Varied expressions of colorism, racism, anti-Indigeneity, and anti-Blackness denigrate and erase Indigenous and especially African cultural influences and ancestries. This hierarchy encourages blanqueamiento [whitening] by reproducing with lighter-skinned people.3 Encountering these logics and practices rooted in imperialism, colonialism, and white supremacy, many of my relatives participated in and experienced the impacts of these oppressive relations.

My great grandparents were born in the western coastal city of Mayagüez under the absolutist and antiautonomous Spanish colonial government of General Romualdo Palacios González in the 1880s. My grandmother, Esther María Irizarry Rubio, shared the same birthplace as her parents and was born in 1913. She benefited from her upper-middle class and light-skinned privileges. Her father served as an administrator for Pro Patria magazine and as a cofounder of El Diario del Oeste newspaper. He later developed Tipografía Comercial, one of two main printing presses in the western part of the largest island. When Esther was five years old, her mother died, shortly after giving birth to her eighth child. Her death represented just one of millions caused by the 1918 pandemic.

Many years later, after graduating from high school, in 1932, my grandmother migrated to the United States. She took the four-day journey from San Juan to New York on the Borinquen ship, which symbolized extractivist power not only in the vessel’s oil boilers but also in the taking and respelling of the Indigenous Taíno people’s name for Puerto Rico to label the ship.4 Joining her oldest sister in New York City, Esther found employment as an IBM typist. The company liked to showcase her ability to translate quickly between English and Spanish. Later, she was hired for secretarial work at Columbia University, where she met a Spanish immigrant who became her spouse. Esther gave birth to my father, Carlos, in 1942, shortly before my grandfather went to war in Europe.

My dad and I have many fond memories of my grandmother. According to my father, she was “una refranera,” a living, walking book of refranes [proverbs]. He also remembered her as having “a lot of affection and goodness.” In my recollections, I recall our singing songs in Spanish and watering her plants together. “Nana,” as I called her, taught me how to dance. When I visited her home, we would squeeze next to each other in her chair and excitedly say, in unison, “¡Uno, dos, tres!,” before using our collective strength to push ourselves into a reclining position. I loved my time with her. Though these memories still fill me with joy and longing to be with Nana again, not all was good in her household in earlier years.

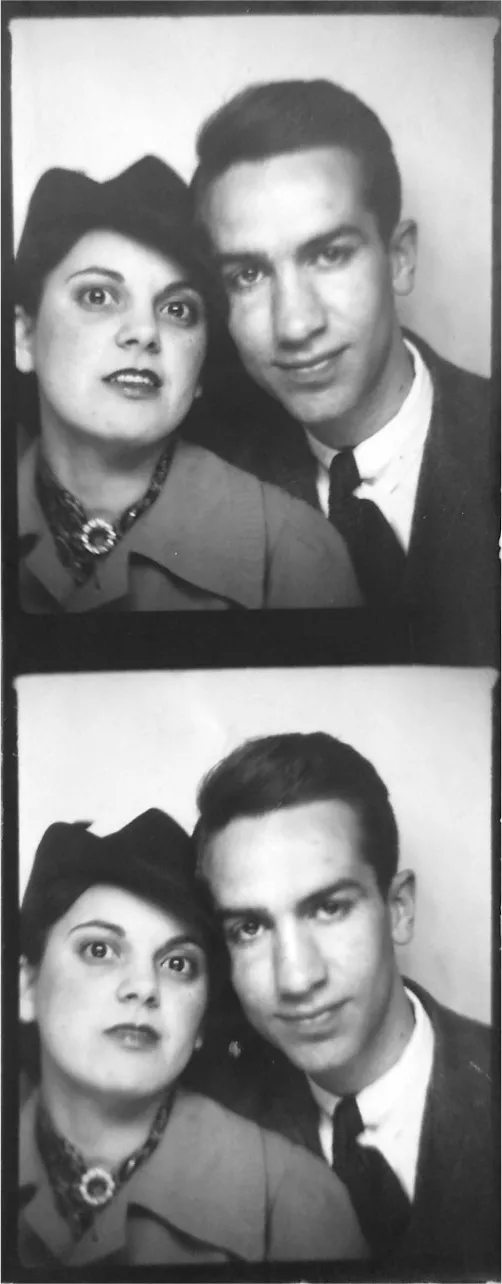

FIGURE 4. My grandparents began their six-decade relationship in New York. Late 1930s or early 1940s. Family photo.

Resulting in much suffering for my grandmother and her children, my grandfather developed boxing skills while at Fort Bragg and was a Central Intelligence Corps officer during World War II. Hence, he could pack a punch and was a trained interrogator. The entanglements of misogyny and colonialism deeply shaped the union of my Spanish-immigrant grandfather and my Puerto Rican grandmother. According to multiple sources, my grandfather snarled at her and said, “When the Spaniards came to Puerto Rico, your people still were hanging from trees.” These cutting words exemplified my grandfather’s colonial machista ways that stemmed from and contributed to a violent familial tutelage, passed down from Spanish fathers to their sons. Over the years, I have heard explosive tempers and cruel actions to discipline, dominate, and dehumanize women and girls in my family described and dismissed as expressions of “energy.”

FIGURE 5. My dad and his cousin race along a Puerto Rico shoreline. c. 1950. Family photo.

Many miles and an ocean away, my grandmother’s Puerto Rican brothers remained in the Caribbean. Guillermo served as Puerto Rico’s budget director under Puerto Rican Governor Luis Muñoz Marín and as secretary of state under Governor Roberto Sánchez-Vilella. In contrast, one of his older brothers, Humberto, was a journalist and an independentista [independence advocate]. On the day of the Ponce Massacre, Palm Sunday 1937, US colonial authorities responded to an unarmed nationalist protest by killing twenty people and wounding more than 150 others. Humberto had planned to attend, but my great grandfather forbade his participation, so he stayed home. My father also recalls Humberto’s story of being questioned by local police for his proindependence activities. He was very fortunate to avoid the persecution and violence that many other nationalists faced.5 My dad met and spent time with Guillermo and Humberto when he returned to his mother’s birthplace, which helped him to understand both her origins and his own.

After the war, my father moved incrementally west with his parents, ultimately contributing to settler colonialism in Colorado. Around 1950, my grandfather purchased a small home. When a white neighbor, who also was a minister, discovered “Hispanics” would be joining the neighborhood, he unsuccessfully created and circulated a petition to bar their move. Meanwhile, my dad sensed his otherness from the white, English-speaking children with whom he grew up. Until kindergarten, he only spoke Spanish. In elementary and middle school, his primary language was English, given structural monolingual dictates, as well as his family’s efforts to assimilate him. However, my father recalled understanding and listening to his parents speak Spanish with each other at home and often in public. This language exposure enhanced his ability to relearn Spanish in high school. A few years later, during his college junior year abroad in Spain, my dad made the political decision not to speak Castilian Spanish, with the strong th sound. He explained that this act consciously sought to honor his mother and his Puerto Rican identity.

Unlike my father, I have chosen, for the most part, to exist between cultures—an option he and so many others like him do not have. I cannot begin to equate my realities with the experiences of first-generation diasporic or Puerto Rico–born individuals. As a Diaspo-Rican, I feel both stranger to and sometimes at home in the archipelago, although I know the Antilles is not my home nor should I try to make it my place to occupy. To visit the Mayagüez cemetery, where numerous family members are buried, creates in me a sense of connection, while also a feeling of being apart. My privileged positionality allows me to visit and leave as I please by having the choice to deepen ties to my ancestral routes/roots, while benefiting from my ability usually to fit in when needed in the United States. These reflections are not intended to suggest my experiences always have been easy, as I often had different cultural perspectives and an ethnicized physical appearance compared to most of the people around me growing up in Montana. I also have struggled to reconnect with parts of my identity that were denied or lost.

While this “Routes/Roots/Raíces” narrates my paternal family history, there is another story that merits acknowledging: my mother’s working-class, Irish-American family. As much as I grew up eating arroz con habichuelas [rice with beans] and pork chops seasoned with adobo, dancing to Gloria Estefan’s Latin American music with mi hermanita, Victoria, and reciting Spanish-language children’s songs and prayers, I also enjoyed learning Irish rebel tunes and danced basic jigs, supported by the unconditional love, sacrifice, and hard work of my mother, Ann. Notably, there are important connections linking Puerto Rican and Irish independence movements, as well as individuals who forcibly and freely moved between these island contexts, but these entanglements are for another time.6 This first “Routes/Roots/Raíces” narrative seeks to show how conquest and resistance exceed tidy binaries of colonizer and colonized. Furthermore, ethnicity, race, class, gender, language ability, and other identity and positionality considerations, intersectional oppressions, and perseverance in the most difficult of circumstances must be part of conversations about Puerto Rico’s energetic past, present, and future.

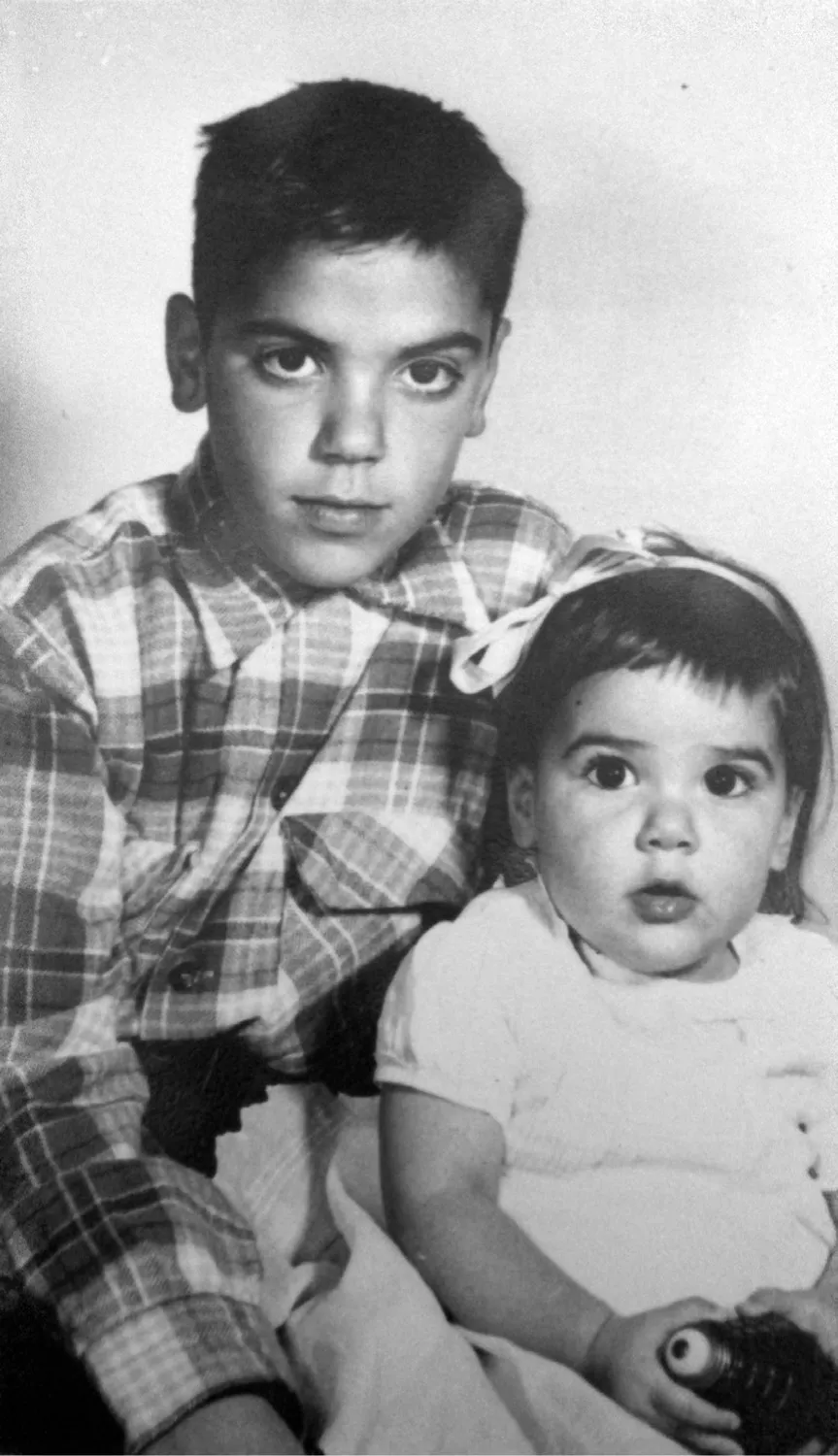

FIGURE 6. My dad and his late sister, María del Carmen, spent most of their youth and young adulthood in the Rocky Mountains of the United States. Boulder, Colorado, 1950s. Family photo.

![]()

ONE

Dis/empowering Terms of an Energy Rhetorical Matrix

THE PREVIOUS “ROUTES/ROOTS/RAÍCES” SECTION provided an account of one family’s experiences in Puerto Rico and in the US diaspora across several generations. This history expressed how different individuals used their energies and power to migrate, harm, care for, work, resist, and create. This chapter continues this historical, energetic interest by interweaving key events, policies, concepts, and interviews to tell one narrative of Puerto Rico, from the late fifteenth-century colonial invasion to the present. To do so, I study how different dis/empowering terms assist in making sense of t...