THE BUILDING OF A REPUTATION

Through annotations in his personal diaries, we know that Whitman referred to the continuous writing and rewriting of Leaves of Grass as “The Great construction of a New Bible.”3 He also referred to his project as “the construction of a Cathedral.”4 Some scholars are of the opinion that Whitman was at all times conscious that he was writing a text that would appear to be mystically inspired, and that the messianic mission, made clear in the 1855 Preface, just became stronger over time.5 Indeed, Whitman, who despised the established churches and clergy, was intensely attracted to religion. Religion was for him the crown of democracy. It was not conventional religion that he had in mind, though, but a new type of religion.

Profoundly influenced by evolutionary theory and scientific ideas of progress, he believed the time had come to replace the old religions with a new one appropriate to the times. Of this new religion, he would be recognized as the prophet and high priest. In light of this, it is not too surprising that an apostolic college should develop around him (“the hot little prophets” as they were called by Bliss Perry, an early and controversial biographer of Whitman), whose members devoted themselves to disseminating the new gospel and glorifying their messiah. Their works generated the myth of Whitman the prophet, the redeemer, the new messiah, a myth that has not endured, but that at the time afforded the poet a controversial role in public life that he skillfully utilized to his advantage. In Asselineau's words, “[t]o some fanatics he [Whitman] appeared as a saint or a prophet, as the equal of Christ or Buddha. In the space of a few years his renown had become international.”6 Whitman's disciples praised him as if he were a new kind of messiah, and Whitman himself encouraged the spreading of the movement to all parts of the world.7

To Emory Holloway, one of the more enthusiastic of his early twentieth century biographers, Whitman was an intellectual and emotional planet big enough to attract lesser minds out of their true orbits.8 If not major literary figures, these little prophets were, nonetheless, individuals of some intellectual standing. For example, Richard Maurice Bucke, a medical doctor and psychiatrist, as well as Whitman's most inspired apostle, was superintendent of an insane asylum in Canada. He had studied in Europe and had received a number of important academic awards, while John Burroughs, another of the poet's inner circle disciples, was a leading nineteenth-century American naturalist.

The authors who took upon themselves the task of spreading Whitman's new gospel were successful in establishing the poet as a (controversial) public figure and, to a large extent, they were also successful in their avowed missionary purpose. Among the works that were responsible for building Whitman's messianic reputation during his lifetime and for years after his death are William Douglas O'Connor's The Good Gray Poet (1866) and The Carpenter (1868), John Burroughs's Notes on Walt Whitman as Poet and Person (1867) as well as Walt Whitman: A Study (1896), Richard Maurice Bucke's Man's Moral Nature (1879) and Cosmic Consciousness (1901), John Addington Symonds's Walt Whitman, A Study (1893), William Sloan Kennedy's Reminiscences of Walt Whitman (1896) and The Fight of a Book for the World (1926), Henry Bryan Binns's Life of Walt Whitman (1905) Edward Carpenter's Days with Walt Whitman (1906), Horace Traubel's With Walt Whitman in Camden, an oftentimes trivial, but still truly monumental, nine-volume record of his conversations with the poet during the latter's last four years of life, and In Re Walt Whitman (1893) by Horace Traubel and Whitman's literary executors. Of the above authors, Symonds, Kennedy, Carpenter and Binns were British, and by no means the only British disciples.

From early on, the missionary impulse crystallized in the form of an international federation, The Walt Whitman Fellowship International, founded in Philadelphia in 1894, two years after the death of the poet, with the stated goal of extending the influence of Whitman's writings. It developed chapters and associated clubs in New York, Chicago, Atlanta, Knoxville, Canada (Toronto and Bon Echo), Bolton (England), Germany, France and other places. The Fellowship emanated out of the Walt Whitman Reunion (or “Re-Union”—we find both spellings in the documentation), a more informal group that had been meeting regularly since 1887 to celebrate Whitman's birthday.9 That same year, an attempt was made by Sadakichi Hartmann, a young multifaceted critic of Japanese-German origin, to found a Whitman society in Boston, but he could not find enough support for his project.10 In 1919, after the death of Traubel—a Boswellian biographer to the poet, the John of the apostolic college, and the indefatigable heart and mind of the Whitman movement—the Walt Whitman Fellowship properly ceased to exist, although it reconstituted itself in 1920 as The Walt Whitman Foundation, and as such became incorporated in 1945. As late as 1958, there was still at least one active chapter of the Fellowship in Chicago.11 As with the Reunion, the Fellowship held yearly meetings on May 31, to celebrate Whitman's birth. These meetings attracted “[s]ocialists, anarchists, communists, painters, poets, mechanics, laborers, business men [ … ] drawn together by the magnetism of a common love.”12 Traubel was not only one of the founding members of the Fellowship but also its secretary and treasurer during the approximately twenty-five years that the organization was in existence. There were fifty-four people present at its foundational meeting in 1894. By 1903, records show it had two hundred and forty members. By this time, the Fellowship held its meetings at the Hotel Brevoort, on Eighth Street and Fifth Avenue, in New York, and its attendees included famous anarchist Emma Goldman and writer Walter Lippmann. It wasn't always a smooth ride for Traubel, who had problems collecting the dues (initially $2 per year). After 1896, it was decided the Fellowship would depend upon voluntary contributions. However, a large majority ignored Traubel's requests for contributions, a minority simply refused to contribute, and only a small number of them did pay.13 This prevented the organization from advancing its publications program, which, after the first few years, was left to its bare minimum.

In March 1890, Traubel began publishing The Conservator, a quality monthly review that reached a circulation of about one thousand. Devoted ultimately to disseminate Whitman's poetry and his message of comradeship, The Conservator regularly featured articles by Whitman's most fervent disciples, together with progressive, even radical, articles on a variety of social and political issues. On its pages we oft en find articles in support of Socialism, against war, for women's rights and vegetarianism, and against vivisection, racism, anti-Semitism, and the death penalty (which Whitman had consistently opposed14), all of it side by side with articles on spirituality, religion, ethics and, of course, central to every issue, Whitman and his work. The paper also kept track of all new reviews and criticisms of the poet. It also promoted the sale of his poetry through large display advertising. Although labeled “an American Communist” by the German press,15 Traubel, who leaned towards anarchism rather than communism,16 did not shy away from publishing opposing viewpoints, and negative, or even openly hostile, criticisms of Whitman or of himself.

An indefatigable Traubel ran and edited The Conservator all by himself for thirty years—a truly colossal task. Occasionally, in the later years of the paper, he was the sole writer in some issues. He managed to keep the monthly publication running until 1919, the centennial of Walt Whitman's birth. Shortly after the publication of the last issue Traubel died. Gary Schmidgall, in his excellent compilation of articles from The Conservator, brings our attention to the final line of the last article in the last issue of the paper: “Leaves of Grass—biography of a man—is the biography of God.”17

The missionary writings published during Whitman's lifetime by O'Connor, Carpenter, Burroughs, Bucke, Kennedy, and Traubel, the poet himself approved of, as well as of the kind of messianic aura they invested him with. In fact, quite often Whitman edited the texts or, as in the case of Burroughs's Notes, shamelessly did part of the writing himself (perhaps as much as half the book).18 When, years later, Burroughs published his Walt Whitman, A Study, a more ambitious work intended as a critical study, even there his criticism is in essence Whitman's conception of himself, not the expression of an independent judgement.19

As a matter of fact, in these extensive missionary writings Whitman was presented in precisely the way he wanted to appear to the world—although that was not always the case. A number of European maverick disciples—among them, British scholars Edward Carpenter and John Addington Symonds, and, in Germany, Eduard Bertz, the most belligerent of all,20—insisted on seeing Whitman as a homosexual prophet, a role that the poet emphatically denied.21

Born in Long Island, N.Y., in 1819, Whitman lived most of his life in the city of New York and its vicinity. Life in New York allowed him to be in contact with and absorb the artistic and intellectual currents of his time, as well as the popular pseudosciences. A source of inspiration for his worldview, as well as an important support for his messianic claims, came from phrenology. Its novel terminology provided the basic paradigm for Whitman's ideal man (or “superman,” as it is referred to by some authors), and a solid justification for his own messianic aspirations. Whitman's steadfast belief in this pseudo-science had a profound influence on his work, not only as the source of some of his most suggestive terminology, but also in shaping the ideal human he represents himself to be in Leaves of Grass.22

As early as 1849, Whitman visited Fowler and Wells's phrenological cabinet in Nassau Street, with the intention of having his phrenological chart done. Believers in this pseudoscience had their intellectual and emotional capacities, and even their moral tendencies, evaluated on a scale of 1 (minimum) to 10 (maximum). The number of points for each capacity or tendency measured depended literally on the size and shape of cranial bulges, forehead and overall volume of the head (on the assumption that these reflect the shape and size of the brain). Although Whitman's “chart of bumps” was unsurprisingly flattering, he probably felt that, after all, he knew himself better than the phrenological experts, and decided to improve his scores by small amounts.23 This he did in an obvious attempt to strengthen his extraordinary claims about himself. Whitman published the improved chart on at least three different occasions as a credential for Leaves of Grass.24 As an extended explanation to the chart, in several editions of Leaves of Grass he even reprinted some of the most flattering comments that Lorenzo Fowler added:

This man has a grand physical construction, and power to live to a good old age. He is undoubtedly descended from the soundest and hardiest stock. Size of head large. Leading traits of character appear to be Friendship, Sympathy, Sublimity and Self-esteem, and markedly among his combinations the dangerous fault of Indolence, a tendency to the pleasure of Voluptuousness and Alimentiveness, and a certain reckless swing of animal will, too unmindful, probably, of the conviction of others.

This was precisely the light in which Whitman wanted to be seen by the world. Even negative traits such as voluptuousness, indolence, animal will and unmindfulness had in Whitman's mind the most seductive connotations, which made them an essential part of his idealized self-portrait:

Walt Whitman, a Kosmos, of Manhattan the son, Turbulent, fleshy, sensual, eating, drinking and breeding, No sentimentalist, no stander above men and women or apart from them. (“Song of Myself,” 24)

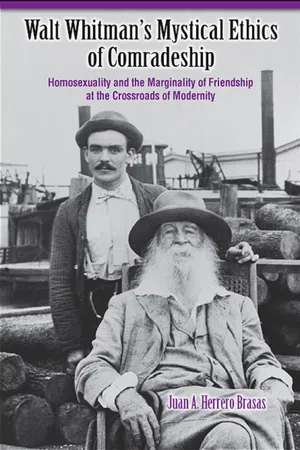

Sometimes he would publish his reviews anonymously (under the guise of an independent observer);25 at other times, he would ask someone else to sign what he had written, as he did, for example, with the Introduction that appeared in the first British edition of Leaves of Grass.26 In other cases, he would encourage such descriptions by others to the point of editing their texts, as pointed out earlier. In O'Connor's The Good Gray Poet (1865), the attempt is clearly visible to link the poet's idealized physical appearance with his messianic mission—the physical appearance being the expression of the inner illumination:

[A] man of striking masculine beauty—a poet—powerful and venerable in appearance; large, calm, superbly formed; oftenest clad in the careless, rough, and always picturesque costume of the common people [ … ] I marked the countenance, serene, proud, cheerful, florid, grave, the brow seamed with noble wrinkles; the features massive and handsome; the eye brows and eyelids especially showing that fullness of arch we...