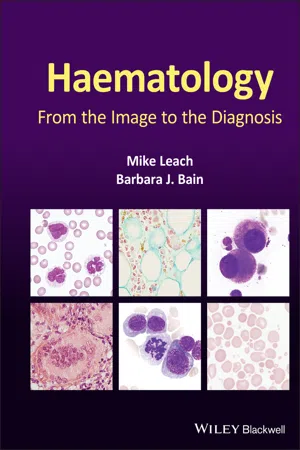

Haematology

From the Image to the Diagnosis

Mike Leach,Barbara J. Bain

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

Haematology

From the Image to the Diagnosis

Mike Leach,Barbara J. Bain

Über dieses Buch

Haematology

Diagnostic haematology requires the assessment of clinical and laboratory data together with a careful morphological assessment of cells in blood, bone marrow and tissue fluids. Subsequent investigations including flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry, cytogenetics and molecular studies are guided by the original morphological findings. These targeted investigations help generate a prompt unifying diagnosis. Haematology: From the Image to the Diagnosis presents a series of cases illustrating how skills in morphology can guide the investigative process. In this book, the authors capture a series of images to illustrate key features to recognize when undertaking a morphological review and show how they can be integrated with supplementary information to reach a final diagnosis.

Using a novel format of visual case studies, this text mimics 'real life' for the practising diagnostic haematologist – using brief clinical details and initial microscopic morphological triage to formulate a differential diagnosis and a plan for efficient and economical confirmatory investigation to deduce the correct final diagnosis. The carefully selected, high-quality photomicrographs and the clear, succinctdescriptions of key features, investigations and results will help haematologists, clinical scientists, haematology trainees and haematopathologists to make accurate diagnoses in their day-to-day work.

Covering a wide range of topics, and including paediatric as well as adult cases, Haematology: From the Image to the Diagnosis is a succinct visual guide which will be welcomed by consultants, trainees and scientists alike.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Information

1

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma with haemophagocytic syndrome

MCQ

- ALK‐negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma:

- Generally occurs at an older age than ALK‐positive cases

- Has a better prognosis than ALK‐positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma

- Has similar histological and immunophenotypic features to breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma

- Is usually associated with t(2;5)(p23.2‐23.1;q35.1)

- Usually presents with localised disease

For answers and discussion, see page 206.

2

Bone marrow AL amyloidosis