![]()

Part One

Perspectives on the Global

Financial Crisis

![]()

1

Moral Hazard and Equity Finance: Why Policy has been Sub-optimal since the Global Financial Crisis

C.A.E. Goodhart

Introduction

Whereas this chapter was written before the coronavirus pandemic struck, I see no reason to amend or alter any of its contents and arguments. Its thesis is that macroeconomic policy remained sub-optimal in the years between the Great Financial Crisis and the onset of COVID-19. The main reason why this has been so is that there has been a generalized failure to appreciate the moral hazard that was introduced into the modern capitalist economy by the legal institution of limited liability for all equity holders. The incentive structure induced by limited liability has led corporate managers, notably bank managers, to seek excessive risk and leverage in the pursuit of return on equity (RoE), egged on by shareholders. There has been a tendency to accuse bankers of moral failings; whereas there is little evidence that bankers are significantly different from other humans, except, perhaps, in having better numerical and computational skills. An associated failing has been to anthropomorphize banks, and treat them as if they were human beings, whereas non-sentient institutions banks have no emotions and cannot make decisions; only bankers can do that. While the policy measures of requiring banks, especially larger banks (SIFIs), to hold significantly more equity capital, has been correct and helpful, the failure to deal with the underlying moral hazard has meant that bankers still have a strong incentive, in pursuit of RoE, to avoid or evade, and manipulate, the regulations, rather than internalize the optimal level of social risk-taking. Section 1 gives a fuller analysis of the implications of the moral hazard inherent in limited liability for all equity shareholders.

This has been one of the factors, amongst several, which has led to investment ratios remaining low, and a surplus developing for the non-financial corporate sectors, in many of our countries, despite the extraordinarily expansionary monetary policies and the high corporate profitability enjoyed by the corporate sectors in most advanced countries. This is documented and further described in Section 2. Again, whereas the expansionary monetary policy was certainly a great improvement on doing nothing, nevertheless it has been accompanied by relatively low investment, stagnant productivity and low wage growth.

This has also led our economies to fall into a debt trap. Although the leverage ratios of banking sectors, and of households in those countries most affected by the Global Financial Crisis, have been pared back, the debt ratios of non-financial corporates and of the public sector have, in many, perhaps even most, cases risen sharply during the last ten years. Such debt ratios have grown so large that it will be difficult for central banks to raise interest rates significantly, or fast, without increasing debt service payments to a level that will potentially place corporate solvency at risk, or in the case of the public sector, be yet another factor leading to the need for increased taxation, with worsening intergenerational inequality. This is discussed in Section 3.

I conclude in Section 4 by suggesting alternative policies which could help to extract us from this debt trap. This has two main planks, both of which involve institutional change, with the purpose of bringing about a major shift in the financial structure of our economies towards equity finance, and away from debt finance.

The first institutional change would be to eliminate the fiscal advantage that debt finance currently enjoys over equity finance. This has already been proposed, and suggestions made as to how this might be introduced first, in the Mirrlees’ book, Tax By Design: The Mirrlees Review (2011), and, second, in the paper on ‘Destination Based Cash Flow Taxation’ (often otherwise called ‘Border Taxation’, see Auerbach et al. 2017a and b).

The second institutional change would involve introducing a legal distinction within equity finance, whereby there are separate categories of shareholders. The first category would involve insiders, i.e. those who have both inside information and the ability either to influence or control the decisions which the corporations makes. These would have multiple liability, possibly, in the case of the CEO, unlimited liability. The second category would be outsiders, who have neither inside information, nor the ability to influence or to control corporate decisions. They would retain limited liability, as at present. The case for doing this is set out in greater length in the associated paper by Professor Rosa Lastra and myself, ‘Equity Finance: Matching Liability to Power’ (Journal of Financial Regulation, March 2020). Again, an alternative would be to require the same set of insiders to be paid primarily in bail-inable debt; see T. Huertas, ‘Pay to Play’ (2019).

1. The moral hazard of limited liability

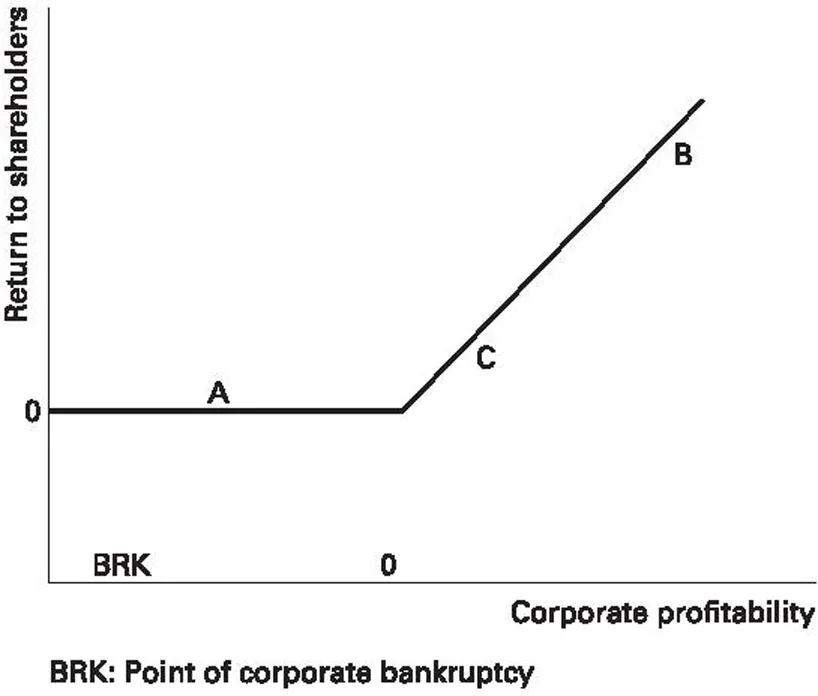

A consequence of limited liability for shareholders is that the return to their investment, as a function of the profitability of the firm in which they have an equity share, is flat when the company is doing badly or becomes insolvent, but slopes upwards strongly when the public company is doing well. This is shown graphically in Figure 1.1 below.

With a return structure of this kind, the shareholders are led to prefer a riskier strategy, as shown in the figure, with an even chance of an outcome of A and B receiving a return equal to the mean profit to the corporation of AB, rather than a completely safe policy, as shown in the diagram at point C. So, shareholders have an innate preference to encourage management to take on riskier activities. Such shareholder preference for risk is somewhat abated by loss aversion; see, for example, Kahneman (2012). But that, in turn, is reduced by appropriate diversification, so that the loss involved on any single portfolio holding is limited. So, the implication is that limited liability naturally leads shareholders to push management to adopt riskier strategies than would be socially optimal.

Figure 1.1 Corporate bankruptcy.

In earlier decades, before the 1990s, this pressure on management was mitigated by the fact that managers were primarily paid by a cash salary unrelated to equity valuation. Moreover, other considerations, such as reputation and pride in developing a successful company over the long term, had the effect of constraining managers willingness to take on risk. But one of the other possible incentives on managerial behaviour, as a result, was to spend resources on activities that might bolster managerial reputation and personal comfort, rather than maximizing profits. Such considerations involved size and spending money on managerial perks, including not only such perks as company planes and chauffeur-driven cars, but also fancy, prestigious architecture, head offices, etc. The cry went up, as a result, that managerial incentives should become better aligned with the interests of shareholders, possibly one of the worst ideas developed by academic economists in recent decades!

Partly in response to public attitudes then, about soaring managerial pay and perks, President Clinton introduced measures in 1993,

when he effectively set a $1 million limit on directors’ pay by making anything above that level non-tax deductible for companies. However, in the small print of his legislation, was a clause that specified payments with performance conditions were exempt from the $1 million rule. That effectively meant company boards boosted all salaries to $1 million and paid bonuses and extras in stock options that directors could cash in for shares at a later date. This prompted an explosion in executive awards…

Hargreaves 2018: 77

The result of such alignment of managerial incentives with those of shareholders, in some large part done consciously, resulted in there being the exact same incentive on management to give priority to policies that would maximize equity valuation; naturally this would generally lead them to pursue additional risk. Moreover, the expected lifetime incumbency of most CEOs is relatively short – five years or less – and that means that the incentive on them is to maximize short-term equity valuations. This can most easily be achieved by accepting a riskier financial structure, e.g. buybacks to increase leverage and raise RoE, reducing employee headcount and cutting out such longer-term investment, notably in R&D, the return on which was unlikely to become clear for a long time.1

So, the criticism of modern capitalism has several facets; it is argued that it leads to managers assuming excessive risk, being overpaid and failing to undertake sufficient long-term investment, especially R&D. The first two criticisms, excessive risk and excessive pay, were particularly levied at banks and other financial intermediaries in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis. There have been a variety of proposals aimed at checking or preventing such malfunctions. One set of such proposals has focussed on limiting the business structures of banks and other financial intermediaries. Examples of such proposals include narrow banking in various guises, ringfencing of core retail financial structures and a variety of other regulatory measures. A recent addition to this set is by Conti-Brown (2012), arguing for the abolition of limited liability for SIFIs, unless they become very highly capitalized.

Another set of responses, aimed more widely at the general governance structure of (public) corporations, has considered such remedies as two-tier governing boards, as can be seen in the German system, and changing the statutory duty of governing boards, for example as argued by Schwarcz (2014).

A third, and final, set of proposals, including those in the accompanying paper by myself and Rosa Lastra, would adjust the link aligning the interests of shareholders and managers, by imposing additional duties on managers, either through tougher legal requirements (see Kokkinis 2018), or by changing the incentive and remuneration terms for management.

2. Why has non-financial corporate investment been so low?

Ever since the financial panic accompanying the Global Financial Crisis abated in 2009, conditions for the corporate sectors in most advanced economies have become extremely favourable. The share of corporate profits in national income over the years 20...