eBook - ePub

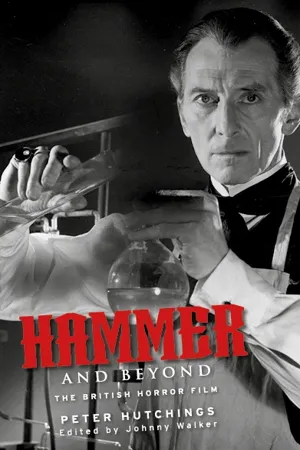

Hammer and beyond

The British horror film

Peter Hutchings, Johnny Walker, Johnny Walker

This is a test

- 328 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Hammer and beyond

The British horror film

Peter Hutchings, Johnny Walker, Johnny Walker

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Peter Hutchings's Hammer and beyond remains a landmark work in British film criticism. This new, illustrated edition brings the book back into print for the first time in two decades. Featuring Hutchings's socially charged analyses of genre classics from Dead of Night (1945) and The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) to The Sorcerers (1967) and beyond, it also includes several of Hutchings's later essays on British horror, as well as a new critical introduction penned by film historian Johnny Walker and an afterword by Russ Hunter. Hammer and beyond deserves a spot on the bookshelf of anyone with a serious interest in the development of Britain's contribution to the horror genre.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Hammer and beyond als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Hammer and beyond von Peter Hutchings, Johnny Walker, Johnny Walker im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas & Historia y crítica cinematográficas. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Part I

Hammer and beyond: the British horror film

Introduction to the first edition

Certain branches of the British cinema are able to weather any crisis: they do not so much rise above it as sink beneath it, to a subterranean level where the storms over quotas and television competition cannot affect them. This sub-cinema consists mainly of two parallel institutions, both under ten years old: the Hammer horror and the Carry On comedy.1

Francis Wyndham’s remarks, written in 1964, reflect upon the way in which through the last part of the 1950s, into the 1960s and then on to the 1970s, British horror was one of the most commercially successful areas of British cinema.2 As Wyndham indicates, easily the most prolific of horror producers was the relatively small company called Hammer Films, from which there emerged from 1956 onwards a series of gothic horrors, most notably those featuring Peter Cushing as Baron Frankenstein and Christopher Lee as Count Dracula, which were to become famous throughout much of the world.

But the story of British horror involves much more than the activities of the filmmakers at Hammer. For one thing, well over one half of British horror production comes from companies other than Hammer. For another, the significance of British horror derives as much from the critical and popular responses to the films on their initial and subsequent releases as it does from the filmmakers themselves. In order to ascertain the importance and the merit of British horror, as well as the reasons for Hammer’s dominance, we also need to recognise that both creators and audiences exist within and in relation to a particular historical context. Of course, this does not mean that British horror reflects in any unmediated way aspects of British post-war reality. Nevertheless, this book will demonstrate that these horror films do draw upon, represent and are always locatable in relation to much broader shifts and tendencies in British social history. It is equally important, however, to think of these films, on the most basic of levels and regardless of how one values them, as aesthetic and artful constructs which are to a certain extent separate from the everyday concerns and experiences of their intended audience. What this means when we look at the films themselves is that we need to be aware of how they fit into and sometimes diverge from the characteristic practices and concerns of British cinema at the time of their production. Only in this way can a sense be gained both of their social resonance and their cinematic specificity.

It follows from this that the aim of this book is primarily a cultural-historical one. In particular, the book will trace the changing nature of British horror from the mid-1940s to the present day as it constantly seeks to redefine itself in the face of social change. In so doing, films of some distinction will be identified and discussed. But the worth of British horror does not reside entirely, or even perhaps mainly, in these. Instead, the genre itself, or movement if you prefer, the possibilities it offers and all the films it contains, can be seen in total as offering a rich, fascinating and multifaceted response to life in Britain over the past few decades.3

I would like to thank Charles Barr for his invaluable comments on an earlier version of this book. I would also like to thank the students and colleagues with whom I have worked over the years who, in all sorts of ways, have supported and encouraged this project.

This book is dedicated to my parents, John and Rosemary Hutchings.

Notes

1 Francis Wyndham, ‘The Sub-Cinema’, Sunday Times Supplement, 15 March 1964.

2 On the Carry On films – still a relatively unexplored area of British film production – see Marion Jordan, ‘Carry On – Follow That Stereotype’, in James Curran and Vincent Porter (eds), British Cinema History (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1983), 312–27.

3 British horror can be considered both as a sub-genre, a category of international horror production, and as a nationally specific movement with a finite beginning and end. I discuss this in more detail in the first chapter of this book. Suffice it here to indicate that later in the book when I discuss the genre of British horror, I mean to refer to a distinctive area of British cinema which has affinities with and can be related to horror films produced elsewhere, but in very important ways is separate and unique.

1

For sadists only? The problem of British horror

Horror is often a problem for critics. The all too visible stress in many horror films on morbid themes and acts of violence; the openly exploitative nature of much horror; the association of the genre with a predominantly adolescent audience: all these factors militate against the horror genre being viewed in anything but the most derogatory or patronising of terms. So much is this the case that even those critics who want to argue for the worth of these films sometimes find themselves negotiating what appears to be an inhospitable terrain, with their work taking on an accordingly defensive tone. Nowhere is this unease more evident than in the various critical responses provoked by British horror cinema over the years. From the outraged to the laudatory, these responses are part of the baggage which British horror inevitably brings with it to any critical discussion. If we are to move beyond some of the less helpful long-standing assumptions about horror and towards a more systematic understanding of this sector of British film production, we need to consider this legacy of criticism.

For our purposes, the press reviews and other critical articles and books that appeared between 1956 and the early 1970s – the period which saw British horror’s great box office success – are of particular interest. These critical pieces form a significant part of the cultural climate within which British horror was created and developed, and for that reason alone are relevant to a contextual understanding of the genre. The relationship between criticism and film production needs to be seen as a two-way process. It is not just a question of films being made and then being critically appraised. It is much more interactive than this, with critical attitudes being defined and redefined in relation to trends in film production and, at the same time, filmmakers responding to these attitudes, sometimes reacting against them (see my later discussion of Michael Reeves in this respect) but often, as in the case of Hammer, cheerfully accepting the place allotted them within a particular map of British cinema.

It is fair to say that the critical verdict on British horror during the time of its proliferation was overwhelmingly negative. More positive critical evaluations began to appear in the early 1970s when horror production (and indeed much of the rest of British cinema) was beginning to wind down. Most notable among these was David Pirie’s 1973 book A Heritage of Horror which sought to locate horror cinema within a British gothic tradition.1 Another approach which has since become apparent is to view British horror as part of ‘the dark side’ of British cinema, ‘a lost continent’ still waiting to be rigorously explored and mapped. The ‘dark side’ metaphor is especially potent in that it suggests not only a repression on the part of earlier critics who have refused to engage with the genre, but also that the films themselves are dealing with the release of forces that are repressed in other, more respectable areas of British cinema.

The first part of this chapter explores the various responses to and readings of British horror. It will demonstrate that while some of these, most notably Pirie’s, are more convincing than others, important issues are still not being addressed. In particular, more thought needs to be given not only to the way in which these films relate to the social and historical circumstances of their production but also to how the aesthetic and the commercial imperatives of the genre interact. The chapter will conclude by offering another way of thinking about British horror, one that seeks to take all these factors into account in an attempt to identify what it is that makes the horror film so distinctive and important a part of British cinema.

The press response

The attitudes of British film critics to British horror were to a large extent formulated in response to a series of immensely popular horror films produced by Hammer in the last part of the 1950s. Two things are apparent from a consideration of the press notices of the Hammer horrors of this period. First, British horror, and Hammer in particular, was not as controversial as some histories of horror have suggested. In discussing the critical receptions of two non-Hammer films, Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960) and Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971), Ian Christie and Charles Barr respectively stress the way in which the critics almost unanimously refused to engage with these films on any level.2 A product of this was symptomatic factual errors in the actual reviews. Hammer horror did not receive such treatment. It was, quite simply, not as threatening as the two films cited above. Certainly, emotive words were used to condemn it, but significantly one finds very few factual errors in the reviews in question. One reason for this might be that the Hammer films tended to lack those formal and rhetorical devices used by both Powell and Peckinpah to implicate the spectator in the violence depicted on screen.

Secondly, perhaps as expected, the reviews of British horror films become shorter in length as time passes. Linked with this, they also begin to use a recognisable shorthand based on the name of ‘Hammer’. For example, only two of the available reviews of The Curse of Frankenstein (Terence Fisher, 1957) mention Hammer at all (Sunday Express, 5/5/57, Evening News, 2/5/57). The reviews for Dracula (Fisher, 1958), released one year later, contain a few scattered references to the studio. A year after that we can find, among other references, ‘the horror boys of Hammer films’ (Nina Hibbin, Daily Worker, 28/3/59 on The Hound of the Baskervilles [Fisher, 1959] – ‘the horror boys’ recurs in other reviews by other writers, implying a certain childish, ‘naughty’ quality about the filmmakers) and ‘Hammer Films’ own baleful province’ (Evening Standard, 3/12/59 on The Stranglers of Bombay [Fisher, 1959]). By the late 1960s one finds, typically: ‘Directed by Terence Fisher, The Devil Rides Out is no better nor worse than any other Hammer horror and, of course, stars Christopher Lee’ (Nina Hibbin, Morning Star, 8/6/68 – complete review) and ‘There’s not much to say about The Devil Rides Out except that it’s the latest Hammer horror release’ (Guardian, 7/6/68). Incidentally, The Devil Rides Out is considered by many supporters of the British horror genre as one of its most distinguished films.

Here the name of Hammer is being used as a reductive, descriptive category. Merely to utter it implies a certain type of film, and in particular a certain type of horror film. Merely to invoke it implies a critical response which no longer requires elaboration. On one level at least, this can be viewed more as a response to Hammer’s self-image, its unabashed foregrounding of the formulaic nature of its product. (Another possible reason for the brevity of the later reviews might be the fact that Hammer simply stopped showing certain films to the press from the mid-1960s onwards.)

Of course, this does not mean that the press reviewers were the passive victims of the manipulations of the Hammer selling machine. Undoubtedly they were sensitive to it, often mentioning, in rather distasteful tones, the gaudy posters and tasteless promotional stunts that surrounded the films. One particularly memorable example of the Hammer approach to marketing is provided by the invitations to the press screening of The Stranglers of Bombay – filmed, according to the poster, in ‘Strangloscope’ – which were written on silk scarves similar to those used as murder weapons in the supposedly factual film. In the midst of such activity, and to a certain extent as a reaction against it, the British critics worked to identify Hammer, and British horror in general, in their own way. As we will see in a later chapter, the evaluation of Hammer that emerged was subsequently used as a yardstick against which non-Hammer horrors were judged and valued.

Perhaps the best way to understand this process of identification, as well as the array of critical attitudes that it involves, is to look at the reception of one particular film, in this case The Curse of Frankenstein, Hammer’s first colour horror film, released in 1957. David Pirie describes the critical reaction to The Curse of Frankenstein thus: ‘at the time outraged critics fell over each other to condemn it’.3 While this is certainly true, it is also the case that the virulently negative reviews were far outnumbered by reviews that were, on the whole, either indifferent to or amused by the film. Of the twenty-three press notices available in the BFI archives, only five could conceivably be described as ‘outraged’. These include the reviews in The Daily Worker (4/5/57, Robert Kennedy) and The Daily Telegraph (4/5/57, Campbell Dixon), in the latter of which the following appears: ‘But when the screen gives us severed heads and hands, eyeballs dropped in a wine glass and magnified, and brains dished up on a plate like spaghetti, I can only suggest a new certificate – “SO” perhaps; for Sadists Only.’ Similar attitudes are expressed in The Sunday Times (5/5/57, Dilys Powell), Tribune (10/5/57, R. D. Smith) and, perhaps most notably, The Observer (5/5/57, C. A. Lejeune): ‘Without any hesitation I should rank The Curse of Frankenstein among the half-dozen most rep...

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- A return to Hammer and Beyond: introduction to the new edition

- Part I: Hammer and beyond: the British horror film

- Part II: Selected writings on British horror film

- Afterword

- Select bibliography

- Index

Zitierstile für Hammer and beyond

APA 6 Citation

Hutchings, P. (2021). Hammer and beyond ([edition unavailable]). Manchester University Press. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/2801702/hammer-and-beyond-the-british-horror-film-pdf (Original work published 2021)

Chicago Citation

Hutchings, Peter. (2021) 2021. Hammer and Beyond. [Edition unavailable]. Manchester University Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/2801702/hammer-and-beyond-the-british-horror-film-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Hutchings, P. (2021) Hammer and beyond. [edition unavailable]. Manchester University Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2801702/hammer-and-beyond-the-british-horror-film-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Hutchings, Peter. Hammer and Beyond. [edition unavailable]. Manchester University Press, 2021. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.