eBook - ePub

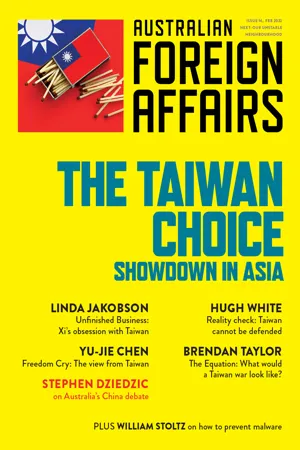

AFA14 The Taiwan Choice

Showdown in Asia

Jonathan Pearlman, Jonathan Pearlman

This is a test

- 144 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

AFA14 The Taiwan Choice

Showdown in Asia

Jonathan Pearlman, Jonathan Pearlman

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

The latest issue of Australian Foreign Affairs examines the rising tensions over the future of Taiwan as China's pursuit of 'unification' pits it against the United States and US allies such as Australia. The Taiwan Choice looks at the growing risk of a catastrophic war and the outlook for Australia as it faces a strategic choice that could reshape its future in Asia.

- Hugh White on why war over Taiwan is the gravest danger Australia might be facing

- Lead essays exploring Australia's military capacity to enter a war over Taiwan; the significance of the strategic choice that lies ahead for Australia; and the view from Taiwan

- Award-winning writer Richard Cooke on foreign policy jargon

- PLUS correspondence on AFA13: India Rising?

Australian Foreign Affairs is published three times a year and seeks to explore – and encourage – debate on Australia's place in the world and global outlook.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist AFA14 The Taiwan Choice als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu AFA14 The Taiwan Choice von Jonathan Pearlman, Jonathan Pearlman im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Politics & International Relations & Geopolitics. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Correspondence

“Pivot to India” by Michael Wesley

Lavina Lee

Michael Wesley’s article “Pivot to India?” (AFA13: India Rising?), shines a much-needed spotlight on the surprisingly underdeveloped relationship between Australia and India. Wesley carefully traces the trajectory of the relationship, from the estrangement of the Cold War era and the depths of discord after India’s 1998 nuclear tests, to the relationship’s recent peak in June 2020, when a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between the two countries was declared.

Wesley offers some key insights into why both countries have neither valued each other nor understood each other’s strategic culture, geopolitical anxieties and predicaments. India’s historical experience as a subjugated rather than a privileged member of the British Empire gave rise to a post-independence worldview characterised by a high value for sovereign autonomy, an affinity with the ‘have nots’ of the global order and a reluctance to take on the mantle of great power status based on “might, coercion and exploitation”. In contrast, Australia’s Anglo-Saxon heritage and experience within the Empire allowed it to place trust and confidence in “great and powerful friends” – first Great Britain, then the United States – to “assuage its central anxiety – that it has too few people to defend such a large landmass”.

That was then. Currently, Australia is dealing with a more economically and militarily powerful India that has the will to assert and defend its regional and global interests. The rise of an assertive and revisionist China, alongside the relative decline in US predominance in our region, has raised the hope and expectation that India will add to the strategic balance preventing Chinese dominance in the Indo-Pacific.

This leads to a central question in Wesley’s article: will India emerge as a new “great and powerful friend” to Australia? While recognising that the two Indian Ocean democracies have increasingly congruent views of China, Wesley warns Canberra against setting its expectations of India too high. Predictions of India’s imminent rise to great-power status have indeed been proved wrong many times before. India’s economic growth has been held back by poor institutions, a restrictive regulatory environment, a dysfunctional democracy and stubborn protectionist sentiments that have persisted since its socialist beginnings.

Wesley could have gone further in recognising other factors preventing India from playing a more robust role in balancing Chinese expansionism in our region. Compared to Australia, India is more vulnerable to Chinese retaliation and has less capacity to absorb punishment. The current border crisis in Ladakh demonstrates both India’s susceptibility to Chinese salami-slicing tactics and how easy it would be for China to stretch Indian forces. Beijing could also encourage Pakistan to challenge to the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir. With a military budget almost four times smaller, and a nominal GDP one-sixth of China’s, India is far more vulnerable to instability in its neighbourhood.

Further, while India has abandoned its formal commitment to “non-alignment”, it retains a deep aversion to alliances and instead pursues “strategic autonomy” via multiple strategic partnerships. Wesley might have acknowledged the reality that this entrenched strategic culture precludes India from playing the role of security guarantor as our “great and powerful friends” have done in the past.

Nevertheless, it is still in Australia’s interest to help India increase its material power on the basis that a stronger India will contribute to a more favourable strategic balance, regardless of whether the two countries are in alignment on all issues. India’s recent enthusiasm for the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue shows its commitment to defending the rule of law, promoting quality infrastructure investment standards, partnering with advanced democracies in emerging technologies and becoming a trusted manufacturing hub and location for supply chains in critical sectors.

In the concluding section of his article, Wesley raises his most contentious arguments. He asserts that Washington has “ceded its pre-eminence in the Pacific” and “Australia will have to adapt to a multipolar regional order”. For this reason, he argues, our “heliocentric perspective is a liability in a multipolar world”.

The foundations for these assertions are not established. While US predominance is in relative decline, it would be premature to conclude that we are entering a multipolar regional order “in which China and the United States become two among a series of great powers … seeking to prevent any single state from dominating the region”. The United States has not yet “ceded its pre-eminence in the Pacific” but has retained and reinvigorated its alliances and increased its forward presence.

Moreover, China might well be emerging as a regional peer competitor to the United States, but we are a long way from a regional order “in which China and the United States become two among a series of great powers”, as Wesley asserts. For example, China spends more on its military each year than the combined military budgets of the whole of Asia and Oceania, and that gap is increasing. This is not suggestive of multipolarity. The iron law of numbers suggests that there can be no regional balance of power without the United States.

To be sure, deepening our relationship with India complements the overall objective of maintaining a favourable balance in the region. But with India’s continuing limitations, Japan’s military and demographic constraints, and Indonesia still some distance away from becoming a significant power, Australia has no choice but to enhance, encourage and support the US presence and power projection in our region and ensure that the United States remains our “great and powerful friend”. The alternative would be to accept a regional order based on Chinese hegemony.

Lavina Lee is a senior lecturer in politics and international relations at Macquarie University and a member of the ASPI Council.

“The Fix”

by Elizabeth Buchanan

by Elizabeth Buchanan

Bob Brown

Canberra’s twenty-year action plan for Antarctica aims to “minimise the environmental impact of Australia’s activities”. The arrival of the new Antarctic ship Nuyina (noy-yee-nah) in Hobart last October met that aim.

Built in Romania and fitted out in the Netherlands, Nuyina is “the world’s most advanced Antarctic icebreaker, science and resupply ship”. It is 160 metres long, 50 metres tall, painted bright orange and almost silent. The ship cost $529 million, and the Australian government has committed $1.9 billion to its operation over the next thirty years.

According to Sussan Ley, Minister for the Environment, “RSV Nuyina will soon be the backbone of the Australian Antarctic Program. It will establish a scientific legacy that will last for generations.”

On the day of the vessel’s arrival in Hobart, Prime Minister Scott Morrison noted that, since the time of Sir Douglas Mawson, Australia has “led the way in the care, protection and understanding of Antarctica … one of the planet’s greatest treasures”.

Nevertheless, in 2018, Morrison flagged a much bigger commitment to building a concrete airport near Australia’s Davis Station in Antarctica – one that would not “minimise” Australia’s environmental impact.

The multibillion-dollar 2700-metre runway, capable of handling Boeing 787 Dreamliners and RAAF Boeing C-17A Globemasters, would require more than 3 million cubic metres of earthworks and the transport from Australia of 115,000 tonnes of concrete pavers.

Sixty vertical metres of the Vestfold Hills would be levelled, using explosives. Nearby Adélie penguin and Weddell seal breeding colonies would face displacement. A lake would be destroyed.

The infrastructure would include a taxiway, aircraft apron, runway lighting and buildings for services such as air traffic, rescue and firefighting.

The Australian Antarctic Division considered building a runway in the Vestfold Hills in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, but it abandoned the idea each time because of the immense environmental impacts involved. Ski-fitted aircraft, using ice runways, were a more flexible aerial alternative.

According to the US aviation news service AeroTime, in addition to increased air connectivity, “another argument for the new aerodrome is Australia’s strategic concerns to counter China’s growing presence in Antarctica”.

In “The Fix” (AFA13: India Rising?), Elizabeth Buchanan agrees: “In theory, the case for developing the runway is essentially benign … but in practice, the Davis runway would be a strategic asset for Australia. It would afford Canberra quick unfettered access to the continent on our southern flank’.

The practical reason for developing the runway is strategic: to create just the menace that the 1959 Antarctic Treaty was meant to avoid.

This boiled down to Australia – a time-honoured leader in keeping Antarctica a global environmental asset, free of commercial and military competition – getting ready to set off a race for strategic control of the continent.

Even if Australia were to offer free and unfettered use of the airport to China, Russia, India and all other nations, how could an Australian concrete runway not give others licence to build their own?

Australia would be offering the perfect excuse for the long-dreaded age of Antarctic commercial and militaristic exploitation, which the Antarctic Treaty, the 1980 Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources and the 1998 Madrid Protocol, prohibiting mining, specifically aimed to prevent.

Buchanan notes that China has plans to build an Antarctic runway of its own at nearby Zhongshan Station (though these plans were stalled, “with Beijing employing a ‘wait and see’ approach to the Vestfold Hills site. Why build on a sub-par site when the best site might remain vacant?”). Like all other airstrips in Antarctica, Zhongshan would be on the ice.

Morrison’s proposed runway was in line with the view of Antarctica expressed by Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce after he visited Casey Station in 2006: “There’s minerals there, there’s gold, there’s iron ore, there’s coal, there’s huge fish resources and what you have to ask is: ‘Do I turn my head and allow another country to exploit my resource … or do I position myself in such a way as I’m going to exploit it myself before they get there.’”

Joyce’s words increased the fears of many of Australia’s Antarctic scientists, who saw a concrete Davis airport as environmental desecration, if not a Trojan horse for exploitation.

They were therefore delighted at the arrival of the Nuyina in Hobart. Here was the perfect next step for facilitating Australia’s historic lead in peaceful scientific research in Antarctica – not least research into the impacts of global warming on the continent, and their flow-on to the rest of the planet.

Three decades ago, the French ship L’Astrolabe docked in Hobart, loaded with explosives and bulldozers to build a runway at its Antarctic Dumont d’Urville Station. This involved blowing up Adélie penguin rookeries. Environmentalists hung a giant banner opposite L’Astrolabe reading “NON!”, and two stowed away on the ship to complicate its progress. In the event, a winter storm smashed the French runway preparations.

If the Morrison government had purloined Nuyina to transfer 10-tonne concrete pavers rather than scientific personnel and equipment to Davis – and that was its plan – there would have been more than banners out to say “NO!” once again.

But on 25 November, after a short but effective public campaign, Minister Ley announced that the government had canned the airport proposal near its Davis base.

Australia was back on track as conservator, rather than concreter, of Antarctica.

Bob Brown is a former parliamentary leader of the Australian Greens.

Donald R. Rothwell

Australia is a major Antarctic power. Australian explorers, scientists, expeditioners and tourists have been travelling to Antarctica for over a century. Australia’s claim to the Australian Antarctic Territory – extending to 42 per cent of the continent – is the largest of the seven territorial claims on the continent. Australia was an original party to the 1959 Antarctic Treaty and in 1961 hosted the first formal treaty meeting in Canberra. The Hawke government promoted an international pivot away from an Antarctic minerals regime in favour of environmental protection. The result was the 1991 Madrid Protocol, prohibiting mining and establishing a comprehensive environmental management regime. Australia has three research stations on the continent, at Casey, Davis and Mawson, which operate year round. The importance Australia attaches to promoting Antarctic science was highlighted in 2021 by the arrival in Hobart of Australia’s new $529-million Antarctic icebreaker, RSV Nuyina.

This backstory, its associated legacies and its contemporary interests are often overlooked in Canberra and the wider community. They provide some context to the government’s November 2021 decision to abandon the Davis aerodrome project.

Australian Antarctic policy, which has enjoyed bipartisan support, is founded on three pillars: support for Australia’s claim to its Antarctic territory, support for the Treaty system and support for Antarctic science. Australia has also practised deft Antarctic diplomacy, including advancing claims to an extended Australian continental shelf in the Southern Ocean from the sub-Antarctic Heard and McDonald Islands, and challenging Japan’s Antarctic whaling in the UN International Court of Justice. The prime example of this diplomacy is the Hawke government’s promotion of the Madrid Protocol, which created an ongoing legacy for Australia and Antarctica. The result is that Australia’s Antarctic environmental credentials are impeccable.

In “The Fix”, Elizabeth Buchanan rightly highlights the geopolitical issues that currently swirl around the Antarctic. Interest in Antarctica has increased considerably in recent decades. While membership of the Antarctic Treaty appears static, scientific engagement is growing. This is partly due to climate change, which is making Antarctica more accessible, and also a more strategic location for climate research. China’s growing interest in polar affairs – it has strong engagement in the Arctic as a growing maritime power and observer on the Arctic Council – should not be underestimated. While not an original Antarctic Treaty party, China has now adopted all of the key instruments and is a very active player in Antarctic law, policy and politics.

There can be no denying that the Davis aerodrome project could have been a game changer for Australia in Antarctica. It would have opened up opportunities for Australian science that previously were only dreamed of, and it would have significantly expanded Australia’s presence in the Australian Antarctic Territory. The importance of Australia being physically present in Antarctica should not be overlooked. Australia’s Antarctic claim is not settled. The Antarctic Treaty effectively neutralises territorial claims. That has not stopped others from positioning themselves to stake a claim if one day the treaty comes to an end. The Davis aerodrome project would only have enhanced Australia’s territorial claims. It would have sent a very strong signal to others about Australia’s intentions.

Ultimately, however, the Morrison government determined that the project was not feasible on the grounds of environmental impact and cost. Balancing science, the environment, budget, Australian interests and Antarctic geopolitics was always going to be a challenge. The Madrid Protocol would have required a comprehensive environmental evaluation prior to progressing the proposal to debate at the annual Antarctic Treaty meetings. The domestic politics would also have needed careful management. Tough questions could have been posed during the 2022 federal election over the Coalition’s Antarctic environment...

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Editor’s Note

- Hugh White: Reality Check

- Linda Jakobson: Unfinished Business

- Brendan Taylor: The Equation

- Yu-Jie Chen: Freedom Cry

- Stephen Dziedzic: Young Guns

- The Fix

- Reviews

- Correspondence

- The Back Page by Richard Cooke

- Back Cover

Zitierstile für AFA14 The Taiwan Choice

APA 6 Citation

Pearlman, J. (2022). AFA14 The Taiwan Choice ([edition unavailable]). Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/2842853/afa14-the-taiwan-choice-showdown-in-asia-pdf (Original work published 2022)

Chicago Citation

Pearlman, Jonathan. (2022) 2022. AFA14 The Taiwan Choice. [Edition unavailable]. Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd. https://www.perlego.com/book/2842853/afa14-the-taiwan-choice-showdown-in-asia-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Pearlman, J. (2022) AFA14 The Taiwan Choice. [edition unavailable]. Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2842853/afa14-the-taiwan-choice-showdown-in-asia-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Pearlman, Jonathan. AFA14 The Taiwan Choice. [edition unavailable]. Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd, 2022. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.