This is a test

- 239 Seiten

- German

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Controlling and the Controller

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Management AccountingBusiness PlanningManagement by ObjectivesRole of the ControllerContents- System of Management Reporting- Contribution Accounting, Cost Accounting and Product Pricing- Profit Centre Organization and Management by Objectives- Graphical Explanation of Facts and Figures- Responsibility and Decision Accounting- Controller's Role and Organization- Strategic Planning and Annual Budget- Variance Analysis and Forecast- Investment Calculation

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Controlling and the Controller von Alfred Blazek, Albrecht Deyhle, Klaus Eiselmayer im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Volkswirtschaftslehre & Wirtschaftstheorie. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Thema

WirtschaftstheorieChapter 1: It's the manager's job to control

A controller doesn't control. This may sound paradoxical, but the controller's job is to provide the best possible information and interpretation of it so that the controlling funtion can be carried out.

So who performs the actual controlling function? It's the CEO (Chief Executive Officer) or manager, as we shall call him or her in this book. It's the manager's job to do the controlling. The controller has to ensure that the managers actually do carry out their controlling. The controller, in short, is an internal controlling consultant.

A controller is an adviser, not an executive. He needs to persuade people to take the right course; he acts through them. The controller manages controlling – getting controlling done by the managers.

The manager's job

A salesman doesn't make a sales manager just because he knows the needs of his customers. Nor is a good engineer, simply by being a good engineer, necessarily cut out to manage a plant or a construction office. The head of the sales department in a pharmaceutical company once said to me after a lecture I had given on contribution accounting: „My dear fellow, here you have to look at everything from a medical point of view.“ There speaks the typical medic! His products require a doctor's prescription. He himself is a trained doctor. But now he's a sales manager too, he needs to look to the financial returns. Otherwise the company's economic health will suffer! And he has to guide people who did not learn the medical profession.

Take another example. A perfectly running machine built by a team of first-rate engineers must also have a price tag. Otherwise those engineers can't be paid for their excellent work. In other words, you cannot build a machine without also calculating its cost. Everything we do in selling, production, purchasing, research and development has to be accompanied by figures. Because we have to exchange goods and services in market place – following the divison of labour laws and the propensity to exchange as has been formulated by Adam Smith in his famous book on „Wealth of Nations“, already 1776.

And the controller is the „engineer of the figure-producing machine“ as a condition to get running the famous „Marktwirtschaft“. He also needs to be an expert. It is not something that can be done in passing.

But what it is exactly that makes a manager? It is not a professional education, whether in economics, law or technical subjects, not to mention physics or theology. Being a manager is not confined to any particular level in the hierarchy. The managing director is not the only manager in the company. Anybody in charge of a group must be a manager. Indeed, even a self-employed individual needs managerial skills. And, of course, managing is not restricted to any particular branch of organised activity. It's just as essential in the manufacturing industries as it is in the service industries, insurance and banking, or running a hospital.

How to construct a management model

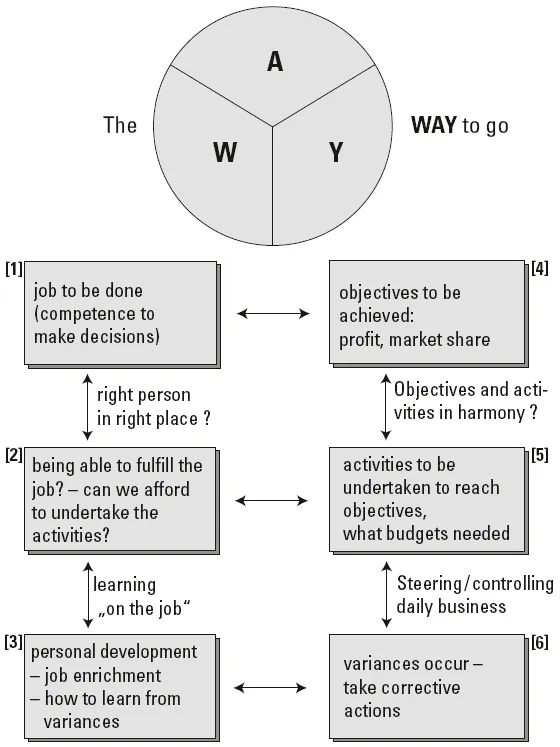

Fig. 2 is an outline management model. As a model, of course, it has to apply to all cases. It doesn't claim to be original: it's simply a system which imposes some order on a tangle of management functions we are familiar with in our day-to-day work. First we have to define the job. The job is what we do. The objectives associated with the job define what we achieve by doing the job. Unfortunately, it is perfectly possible to do a lot and achieve nothing. Now we must ask ourselves: what kind of objectives – what kind of figures – apply to my type of job and responsibility? If I'm a salesman, then my objectives are sales volume and market share. If I'm involved in production, then my objectives are expressed in terms of units, cost per item, quality, i.e. standards of performance. The idea of attainable objectives applies generally to our economic activities. It also applies to sport.

I can play tennis without keeping the score. But then, I'm an amateur. The professional tennis-player watches the score. We could have amateur managers, of course, but the professional manager uses a scoring system.

On the left-hand side of the management model in fig. 2 we have to match the requirements of the job with the capabilities of the men and women employed to perform it. Do we have the right person in the right place? Or is this a case for job development? And if so, does this apply to every body? It's the manager's task to ensure that the people under his guidance are learning on the job and broadening their capacities. He's responsible, in short, for implementing job enrichment. The model's third component is dynamic. This is real life. Jobs, after all, are dynamic, for ever changing, allowing us to discover new potential in ourselves.

Incidentally, our management model works for the top manager in the same way as for the junior manager or the foreman. The junior manager's job is integrated into the senior manager's job – and vice versa. In the same way, the senior manager's objectives include the objectives of those working under him. This is most readily apparent where the top manager is head of sales and those below him are area chiefs. The area chiefs have their own objectives in terms of sales volumes, but these figures are incorporated into the senior sales department manager's overall sales objective figures. Again, the contribution II figure provided by area managers is incorporated in the contribution III figure

Figure 2: Management model

provided by the manager in charge of all domestic sales. When combined with the chief export manager's figures, these contribution III figures produce the sales director's contribution IV figures for total sales.

The right-hand side of the management model (fig. 2) illustrates the controlling process. We now have to ask what kind of activities need to be undertaken to reach the objectives. And what budgets do they need? The plan must say whether the objectives seem to be realistic; the objectives demand appropriate plans and budgets. To bring objectives and budgets into harmony, I should say that two or three budget rounds will be necessary. But, as we all know only too well, we can make a plan, but the best-laid plans seldom work out in practice. We have to recognise this and start making corrections. The need to make corrections is central to the dynamic art of management. But we should not change our plans and objectives because of variances. This would mean that we were painting our targets after we had shot our arrows. And no doubt the best time to make a budget would be the end of the financial year! But, unfortunately, this would leave us without a compass by which to steer our daily business. The advantage of the budget is that it highlights any variances; no budget: no variances.

But we have to make a forecast. We should announce how we think our corrections will be working out up the end of the budget period. This is the rolling forecast which we could make twice or three times a year.

Our management model also shows how plans of action are related to judgements of capabilities. How should we regard a budget proposal? Should a salesman set a sales volume target of 1000, when he really thinks he can reach 1200? If he does, he is off to a flying start. Or should a man budget for the cost of 1000 units when he really only needs 800? Perhaps he is guarding against a possible future cut. So there's more to preparing budgets than just shuffling budget proposals. It's more of a discussion process top down and bottom up.

And the controller is not just someone who tots up figures and staples papers together. He has to take part in he whole business of piecing together the budget jigsaw from the individual bits. At the same time he has to participate in discussions designed to break down the company objectives into individual objectives according to the defined jobs.

Testing the management model

Let's test out the model with some examples. Let's assume we are responsible for selling beer in a particular area. (This means [1] in fig. 2). We must ask the following questions to get our job description: How big is our district? Where are its borders ? What products are we going to sell ? All the company's products, i.e. beer, lemonades and mineral waters? Or are we specialising in just beer? Do our salesmen visit all the customers in our district, or are there special customers, the headquarters of big retailers, for example, who are the province of the sales director himself? What resources have we got for sales promotion? What kind of deductions and bonuses can we offer?

Then we have to match what the job requires with what we are able to do ([2] in fig. 2). We come next to the dynamic concept of job enrichment [3], At first we may just be concerned with selling. Then pricing comes into it. Then sales promotion, then logistics, and so on. On the right-hand side [4] of the management model we need to list the kind of figures representing the objecives of the brewery's district sales manager. Do we express them in hectolitres or sales money, or are we talking about profit, or is it the contribution left once the costs of sales promotion and office administration have been deducted? The lower down the target figure in the area profit and loss statement, the greater the responsibility of the area manager.

The kind of activities ([5] in fig. 2) he has to plan to reach those objectives will include how frequently customers are visited and what steps are to be taken to win new customers. He has to design activities to promote distribution and market share.

We can take a second example to test out the management model, this time from factory management. The job [1] is to promote technical improvement. Do we have the capacity, the potential and the right atmosphere in the company to take new ideas on board [2]? Sometimes we are so overworked that we simply can't afford the time for creative thinking. The objective for the task „improvement“ could be [4] a reduction of hours per unit. Let's assume that in a car factory unit hours should be reduced from 120 to 110. Now the question is how this is to be achieved. Is it by better organisation or smoother work flow? Do we need investment in machinery and equipment? If so, a bigger budget is required. Or do we have to change the product in order to reach our objective of reducing hours per unit [5]? In the end we have to compare the actual results [6] with the objective. Let's assume that we have actually got down to 115 rather than the desired 110. The question is how well was the task of controlling carried out. Did the figure of only 115 hours per unit take us by surprise at the end of the year? Or did we have our hand on the pulse the whole time the show was running? Were there any announcements of delays? The detailed plan must have had shortcomings, and we may well have had to put back delivery dates. Did customers accept this? Announcing delays tends to be better received than just allowing them to happen without a word said.

When we come to diagnosing the variances [6], we find that the problem may lie in the planning of activities [5], and being aware of the facts behind our decisions. So we have to learn from the variances. Controlling is a learning process. But this kind of learning should also take place on the left-hand side of the management model. What kind of training should we undertake [3]? Perhaps we need to improve our teamwork? No one person can implement better solutions; it needs cooperation between all departments, between product development, construction, plant management, logistics, sales, and the controller, of course.

So we see that any event or managerial experience can be pinpointed on our management model, which quite clearly shows that it is the manager's job to do the controlling. The controller's function is to help him by building him a controlling cockpit and advising him on how to use it. So the controller's function must always be understood as a training role. He has to give help in order to enable managers to help themselves. It's a form of self-medication.

Identifying objectives through participation

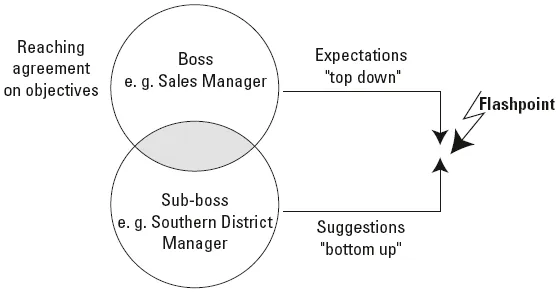

The management model as shown in fig. 2 with its six building-blocks gives us an outline structure of the manager's function. Now we need an additional symbol to show us the participative management process. This may be seen in fig. 3. The circles overlap. This means that the boss and the person working with him are in a dialogue, maybe even in a clinch!

Our management model (fig. 2) applies to the boss and his colleague equally. The boss may be the deputy director of domestic sales, while the middle manager looks after sales for the southern region. Or the boss may be the factory director, but also responsible with the factory manager for one of the factory's departments, maintenance, for example. So the sales volume objective of the manager in charge of the southern region is included in the sales volume objective of the deputy sales director. Similarly, the factory boss's whole cost budget will include the special budget of the maintenance department. Since the factory manager has to set his costs against the transfer prices of his products, all the members of his team have to feel responsible for their respective cost budgets, yield rates and standards of time consumption per unit, as well as for the purchasing prices if logistices is part of the factory manager's responsibility. Otherwise standard purchasing prices for materials and components bought in from outside have to be used instead.

To fix objectives requires bottom up and top down communication. Bottom up, the colleague responsible (in the lower circle) makes suggestions as to what he thinks he can reach as a sales objective for the coming year. On the other hand, the boss in the upper circle has his own ideas as to what level of sales should be reached or what costs are acceptable. The two arrows meet; like terminals they spark each other off. During this lively interaction the boss has to judge whether his colleague has been overcautious in the objectives he has put forward. When the objectives have been agreed, they must be challenging, but capable of realization. If you demand too much, people lose heart and make an early start on their reports justifying their failure to reach the target. But if the challenge is too low, motivation suffers. „Why should we sweat our guts out“, people will say, „if nobody wants us to ?“ Like in any sport, we need a personal goal: „How much can I demand with a reasonable chance of success ?“

Figure 3: Identifying objectives through participation

Nothing succeeds like success. Again we see how controlling is a matter of applied psychology.

The manager, as well as the controller at his side, has to sense whether the figure is right or not quite high enough. If I detect a quaver in my partner's voice, then I know that we have pushed up the sales figure too far or set the costs too low. Alternatively, I have to know who hasn't put all his cards on the table. We might call this social sensitivity.

The overl...

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Foreword – Klaus Eiselmayer

- Foreword – Albrecht Deyhle

- Chapter 1: It's the manager's job to control

- Chapter 2: The Role of the Controller

- Chapter 3: Breaking-even on the Farm

- Chapter 4: The Contribution Accounting Story in the Dolls' Shop

- Chapter 5: Cost Accounting and Product Pricing

- Chapter 6: The Industrial Profit Budget Case

- Chapter 7: Strategic Planning and the Annual Budget

- Chapter 8: Investment decision-making: a case study

- Chapter 9: The Variances Case

- Chapter 10: How to Organize the Controller's Function

- Index

- Impressum