![]()

PART ONE

The Bits and Pieces of Reading

![]()

ONE

Words in Context

Building Blocks of Meaning

What Happens as We Read

Meaning is created as we read, word upon word, clause upon clause, line upon line, paragraph upon paragraph. While reading appears to be a linear process, it is by no means straightforward. This running process calls upon our stored, encyclopedic background knowledge of the world. This knowledge base includes factual knowledge, along with our emotions, thoughts, and feelings. The process may be slowed when we run across an unfamiliar term or turn of phrase, requiring a quick check in a dictionary. We may double back, read again, or return to a book or article later. In these ways reading is slightly more reliable than listening to a story or having a conversation.

Another twist occurs when reading a translated text, such as the Bible. Often there is not a one-to-one equivalence between individual words in different languages. For example, the single Hebrew word hesed has been translated as “covenant love and faithfulness” because one English word cannot convey the entirety of its meaning in English. And a single English word, such as “love” is used to represent at least four Greek words, each of which conveys a different shade of meaning: agapē, philia, eros, storgē, based upon the persons involved in the relationship. A translator needs to make this clear, perhaps by adding a modifier such as “brotherly” when translating philia.

Given that meaning is created as we read, it becomes clear that meaning does not lie in individual words, but rather it accrues as we read words in their larger context, bringing to bear the relationship between our stored knowledge and the text itself. For this reason, we claim that the smallest unit of meaning is found at the phrase or clause level. The question, then, is how do the words in a text play with each other in the process of making meaning as we read?

All about Words and Meaning

Even though individual words require context to become meaningful, we typically turn to an alphabetized dictionary or lexicon to find insight into a particularly difficult word as we read. An alphabetized list is probably the quickest way to access an individual word, but is this the most effective way to figure out what the word contributes to a given passage? Is there another way to organize this knowledge that will return a more effective search? Let us look at the difference between words arranged in a standard alphabetized dictionary and those arranged by topical groups. The first option groups words lexically, the second groups them semantically.

Categories: Lexical and Semantic Domains

When words share a root, they often share aspects of meaning as well. This is easily seen with the most basic change between words: pluralizing a word such as “dog” to “dogs”—My dog went to the dog park to play with the other dogs. Adding an “-ing” changes our furry pet to the verb “dogging” and adding an “-ly” makes an adverb—The child was dogging his father’s steps doggedly. These examples show a shift from the concrete term “dog” to the more abstract terms “dogging” and “doggedly,” which play on the doglike characteristics of loyalty and persistence. In a standard dictionary these terms would be found in alphabetical order, or clustered under the term “dog.” This may be called a lexical group or lexical domain.

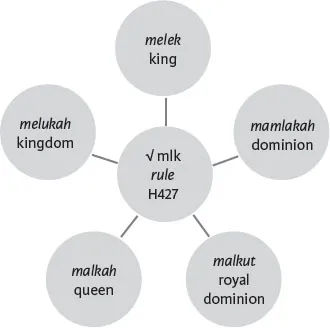

Biblical Hebrew functions in a similar way, with words that cluster together because they contain the same basic three letters, known as the root. The three letters mlk are at the center of a cluster of words that share aspects of ruling or reigning, such as king, queen, kingdom, dominion, and so forth. The shared lexical root gives rise to a lexical domain. In a standard Hebrew lexicon, these and other related terms would be found listed under the three-letter root. The Strong’s Concordance has given an identifying number to each Hebrew and Greek lexeme in the KJV of the Bible. In addition, the volume contains both a Hebrew and a Greek dictionary to describe the meaning of each word. In this case, the identifying number from the Strong’s Concordance has been added to the diagram in diagram 1.1. While the English terms in Strong’s are those used in the KJV, other versions sometimes use different English words to translate the same Hebrew and Greek terms. Nonetheless, the Strong’s numbers are useful for quickly identifying the specific Hebrew or Greek term that underlies the translation, making these numbers useful in other applications. Specifically, the numbers are used to identify the original language terms in both online and commercial biblical studies software and are used in other lexica as well.

This raises another question. What if more than one original language lexeme might be translated with the same English word? In this case, how do we think about other Hebrew words that also are translated as “ruling” or “reigning”? For example, Ruth 1:1 reads: “In the days when the judges ruled,” although the underlying Hebrew term is not from the root mlk. Clearly these words are not be part of the same lexical domain but are clearly associated with one another. In this case, the category would widen to become a semantic domain.

Diagram 1.1 Lexical domains

While lexical domains cluster around lexically related words, a group of words that are similar in meaning create a semantic domain. Semantic domains provide another way of categorizing words, which is extremely helpful when reading longer stretches of text. Semantic domains also play into literary features such as metaphor and can be used to create structure in speech and thought that finds its way to written material, including the biblical text.

Example: Psalm 19:7–9

The list in Psalm 19:7–9 contains a cluster of terms that cohere because they come from the same semantic domain. Here the psalmist has chosen a series of words from the semantic domain of communication, with one outlier—the term “fear” in verse 9 is from the semantic domain of status.

PSALM 19:7–9 (NRSV)

7The law of the Lord is perfect,

reviving the soul;

the decrees of the Lord are sure,

making wise the simple;

8the precepts of the Lord are right,

rejoicing the heart;

the commandment of the Lord is clear,

enlightening the eyes;

9the fear of the Lord is pure,

enduring forever;

the ordinances of the Lord are true

and righteous altogether.

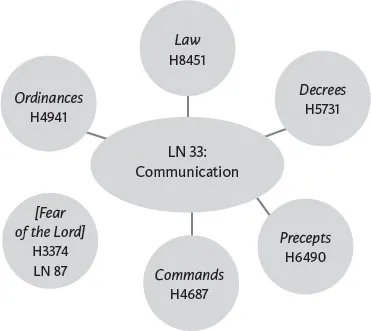

Diagram 1.2 shows the relationship between the underlined terms in Psalm 19:7–9. Five of the six terms are related because they occupy the same semantic domain, that of communication. The Strong’s numbers included for each term show that they are far from being lexically related, as the numbers are not contiguous. Five of the terms—“God’s law,” “decrees,” “precepts,” “commands,” “ordinances”—contribute to the coherence of the section, while the term “fear” breaks the pattern set up by the others. This pattern break adds interest to the section by folding in a term from the semantic domain of honor or respect.

For further discussion of semantic domains in biblical studies it is worth looking at the rise in the study of semantic domains by linguists and biblical scholars as well, including the seminal work of Johannes Louw and Eugene Nida.

Diagram 1.2 Semantic domains

Short History

In the late 1970s and the early 1980s interest in language study shifted from analyzing and describing texts to the examination of language in use. To a large degree this was driven by the burgeoning of artificial intelligence and the rise of technology. Getting computers and humans to communicate seemed nearly impossible at first, but—Siri, anyone?—alongside the development of artificial intelligence, linguists such as Charles Fillmore and George Lakoff, and grammarians such as Ronald Langacker, began to explore language from a cognitive perspective. The claims of linguists and scholars of the “cognitive turn” include the ideas that language is integral to our entire conceptual system, that grammar is conceptualization, and that our knowledge of language comes from using language. These presuppositions have helped to form the way language is studied and viewed today and form the backbone of this volume.

In the 1980s Johannes P. Louw and Eugene A. Nida saw that there was room for improvement in the way that standard biblical studies lexica had been organized. They conceived of reorganizing the information based upon a semantic domain approach. The result, The Greek English Lexicon of the New Testament Based on Semantic Domains, which was first published by the United Bible Society in 1988, with a second edition in 1996. The highlight of the volume is a well-conceived list of semantic domains and sub-domains, which has proven useful not only for categorizing Biblical Greek, but for other languages as well. This was demonstrated by the work of James Swanson, who used the Louw-Nida domain numbers (LN) to keep track of myriad Hebrew lexemes. In 1997, Swanson’s volume, A Dictionary of Biblical Languages with Semantic Domains: Hebrew (Old Testament) was published by Logos Research Systems. While this project was separate from the Greek-English Lexicon project, Swanson’s careful use of the same framework highlights similarities in the way languages work across cultures.

Related Features in Biblical Studies

Since the biblical text is at the core of biblical studies, much effort goes into understanding the text itself, including original language study, literary observations, and study of the historical and cultural backgrounds of the text. Words and language matter for biblical studies in three notable ways: the role of words in context, parallelism, and metaphor studies.

Words in Context

Because the biblical text is a translated text for many readers, it is important to be aware of the translation theory that stands behind a given translation. Since there is no one-to-one equivalence between Hebrew or Greek as the source language and English, Dutch, German, or any possible target language, translators will work somewhere on a continuum. Some will go for the closest word-for-word translation possible, while others will opt for a dynamic-equivalence translation, one that focuses on the meaning in the target language. In English, the New American Standard Bible (NASB) would be an example of the first, and the New International Version (NIV) would be an example of the second. Duvall and Hayes (2012) provide a full analysis of many English translations. Because of these differences, on occasion there will be a variety of English words used to translate a given Hebrew or Greek word in a passage. This is where standard word studies come in—concordances, lexica, Strong’s numbers, and other reference works.

Parallelism

Parallelism has long been recognized as a feature of Biblical Hebrew poetry. In the mid-1700s, Bishop Robert Lowth became one of the earliest English scholars to observe the role of parallelism in the Hebrew text. In Lecture 19 in his series, Lectures on the Sacred Poetry of the Hebrews, Lowth categorized parallel lines as synonymous, antithetic, or synthetic (neither synonymous nor antithetic). However, Lowth’s handy categories are not without limitations. Often lines that are purported to be synonymous are not quite synonymous. Words are used that are close in meaning, but not precisely the same. For example, Psalm 114:5–6 (NRSV) reads:

5W...