![]()

Chapter 1

Adapting to Changing Conditions

In this chapter, we present the major corporate events over recent decades that have formed the Maersk organization into its current form evolving from an international conglomerate to a focused business group with an increasingly diverse workforce with a global presence. These corporate events can be interpreted as ongoing responses to the changing conditions in the global business environment that require adaptive moves if the organization is to remain competitive.

For a multinational enterprise in particular, the adaptive moves derive from complex interactions between strategic considerations at the corporate headquarters and many operating responses performed in various functional units and (possibly) numerous overseas business entities as they deal with the local market requirements. The environmental conditions across the many countries where the enterprise manages its operations may even represent significantly diverse national contexts where practices and customs are vastly different and where customer needs vary. To act in these complex global market contexts requires that the many corporate decision-makers and organizational actors scattered across the multinational enterprise are sensitive to the ongoing environmental changes and identify the factors that drive the impending market changes. Creating an agile organization that is able to adapt effectively across these diverse international market contexts is very demanding and requires a good understanding of the global business environment.

Identifying Market Drivers

Adopting an institutional view on the dynamic interaction within and between organizations and between organizations/firms and civil society/community is to employ a holistic perception of the context in which an organization operates as a social system. Arguably, it is not enough to study the relationship between headquarters and local subsidiaries or country offices around the globe. The study must also consider effects of the institutional setup around the global organization spanning local subsidiaries, country office, and the headquarters. Here we are not only referring to institutions per se but also to the norms and values that govern the functionality of the formal and informal institutions that different parts of the organization relate to.

Institutions are not conceived of as a set of static entities that relate to each other in a given structurally functional way. To the contrary, they are flexible entities in their very constitution due to dynamic external and internal impact factors. The activities of human beings and the organizations they populate in civil society including public and private companies, multilateral entities, governmental, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) of various kinds have two main implications. First, these social systems are characterized by change rather than stasis as the human agents engaged in them constantly assess their position in their institutional context and react accordingly. Second, the institutional frameworks are caught up in an almost permanent process of redefining human agency as the agents that operate within them explore interpretations of the context that can be rather different from the ones initially intended by the institutional setup, thus causing further changes. This may create tensions between governmental institutions and the institutional setup of other organizations embedded in the society or national economy they govern. Governments often work to establish institutional stability, whereas the institutional setup of organizations by definition is in a constant state of flux due to the human agency and changing environmental conditions. Both governments and companies attempt to gain institutional stability but still have to respond to constant societal pressures and changing competitive dynamics to survive and persevere.

Hancké and Goyer (2005) elaborate on this arguing that human agents (in organizations) pursue their own interests that are a direct consequence of ongoing interactions with the institutional framework the agents operate within. Hence, the institutional frameworks may both constrain and offer new opportunities as they allow for new forms of learning that may go beyond the possibilities originally recognized by the established framework. The rationale behind this perspective on the relationship between institutional frameworks and human agency has its root in a phenomenological approach that in particular recognizes the dynamic relationship between context and the individual that results in strategic agency among individual organizational actors.

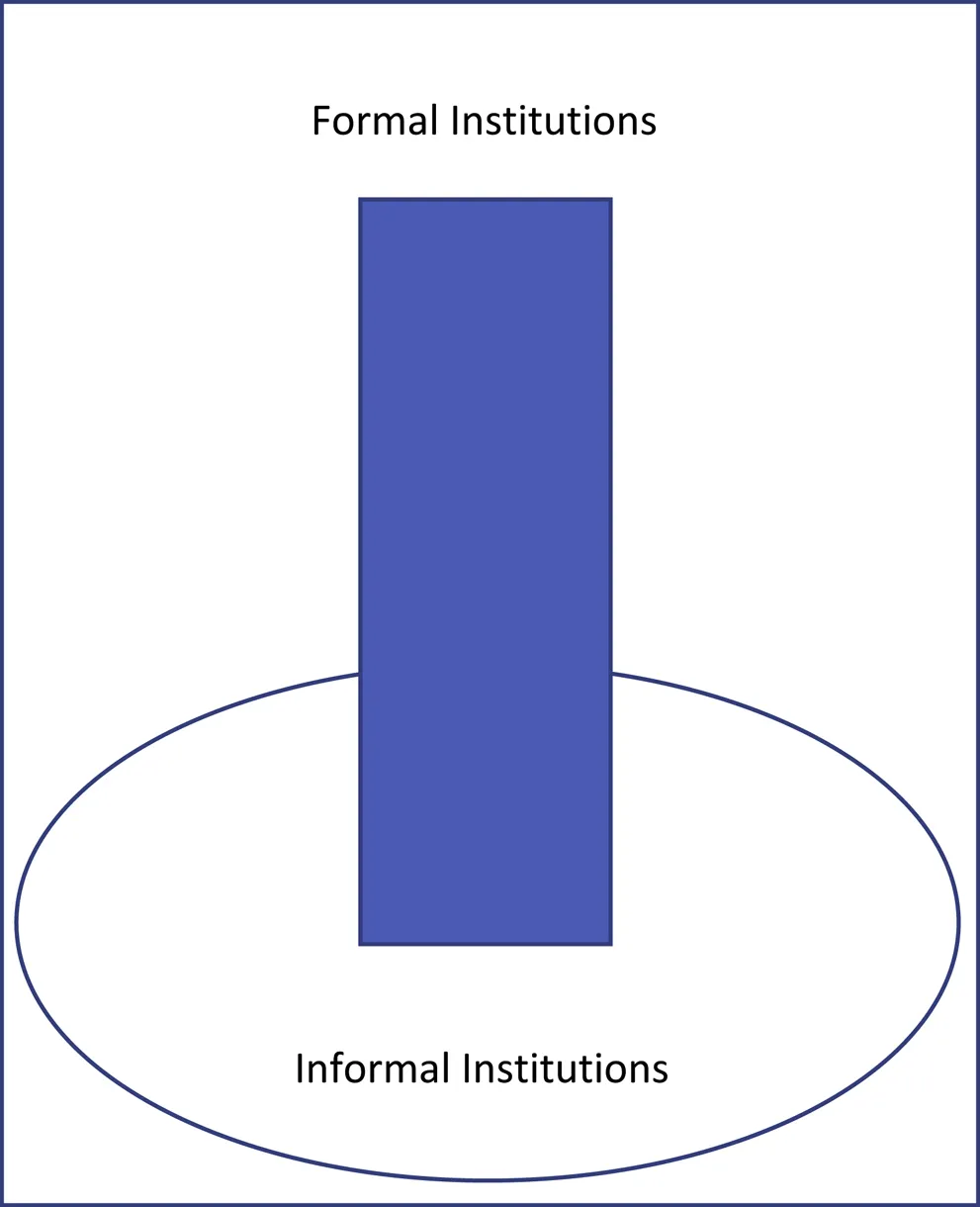

To illustrate this point, we can divide institutions into formal and informal institutions as proposed by North (1991) and Scott (2014). Formal institutions provide policy guidelines, judicial systems, and economic conventions that form the fundamental political, economic, and legal “rules of the game” as a formal basis for acceptable governance of civil society and industry including domestic and international business exchanges. Informal institutions include locally sanctioned norms of behavior embedded in traditional national or regional cultural artifacts and value systems. Informal institutions thus constitute a broader-based set of societal constructs compared to formal institutions and the basic elements that construe localized mindsets, for example, among the employees working in the various kinds of organizations (Fig. 1.1).

Fig. 1.1. A Holistic Institutional Structure.(Source: own creation)

Here it is important not to perceive the two types of institutions as two more or less unrelated sets of institutions as if they cater for different kinds of stakeholders in, for example, governments and civil society, respectively. To the contrary, the formal and informal institutions are closely interconnected and in fact condition the defining elements of one another. This is more so for informal institutions as the human agents that live in the informal institutional norms and values also take up the various positions in the formal institutions to make them function, although not necessarily according to the formal job descriptions. The degree of unpredictable institutional performance partially depends on whether we are talking about developed, transitional, or emerging markets.

We adopt Scott's (2014) sociological understanding of institutional theory, which is a contrast to the view of economists, including institutional economists, who see institutions as resting primarily on regulatory pillars. Douglas North (1991), for example, use rule systems and enforcement mechanisms to define his conceptualization of institutions, thereby emphasizing the formal institutions at the expense of informal institutions.

According to Scott (2014), economists and rational choice political scientists are likely to focus on the behavior of individuals and firms as they act in market places and other competitive situations. They see institutions as rule-based systems where human agents conform to the systems as they act and behave instrumentally and expediently in self-interested ways (Scott, 2014, p. 61). Here Scott (2014) is alluding to a perception shared by many economists that individuals are governed by opportunistic behavior and bounded rationality, qualities that he regards as superficial and simplified. Instead he introduces a third pillar, the cultural-cognitive pillar, as a main driver behind human agency (Scott, 2014). This shared conception constitutes the nature of social reality and the frames through which meaning is made through interaction and maintained or transformed as they are employed to make sense of ongoing happenings.

If we see an organization in this setting, it is imperative to consider these dynamic factors if it is to survive over time in a changing environment. Peng, Sun, Pinkham, and Chen (2009) have developed what he calls a strategic tripod based on international business studies as theoretical approach to deal with this challenges. The model proposes that firm-specific resources and capabilities, industry-based competition, and institutional conditions affect the strategy pursued by a company that makes it able to navigate a given host environment (Fig. 1.2).

Fig. 1.2. A Contingency Model of Company Strategy.

Source: Peng et al. (2009, p. 64)

The contingency model of strategy provides a firm-level perspective and illustrates a holistic view to show the partial influence of the institutional environment the organizations must consider and navigate using firm-specific resources and capabilities to initiate and master that navigation. We will focus on these internal drivers in an organization as they deal with the external drivers in the business environment that together constitutes the context an organization or a company must relate to, respond to, and adapt to in order to thrive over time (Peng, 2002).

From this vantage point, the following briefly reviews three main types of global market contexts in which multinational organizations can find themselves operating. We use the definitions formulated in international business theory to specify these “developed,” “transitional/emerging,” and “bottom of the pyramid” (BOP) markets (Peng & Meyer, 2019).

Developed Markets

These types of markets are defined by rules and regulations, thus leaving little room for influences from the informal institutions. The formal institutions are well established and implemented. We find rather stable political regimes with low levels of corruption and nepotism. These markets typically show moderate growth rates mainly from innovation-driven economic activities. These markets are often referred to as high-trust societies (Fukuyama, 1995).

According to the literature on varieties of capitalism, there are two main forms of markets in this category referred to as liberal market economies (LMEs) and coordinated market economies (CMEs) (Hall & Soskice, 2001). The first market form (the LMEs) is where, ideally speaking, the role of the state is reduced to a minimum and the market has the capability to regulate itself thus reducing the state to a facilitator and moderator in business matters. Countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada fall into this category (Peng & Meyer, 2019). The CMEs are characterized by collaboration between different actors in business, government, unions, and industry associations that coordinate their actions through a variety of mechanisms. These actors are not purely relying on market determinants as the role of the state on top of being a facilitator and moderator also has a regulating function on general market conditions. In economic growth scenarios, the state and its policies leave the initiative to the business actors, whereas economic downturns or recessions engage the state in ways to spur economic activity through various macroeconomic initiatives, such as fiscal stimulus and expansive monetary policy. Countries like Germany and the Scandinavian countries fall into this category (Peng & Meyer, 2019).

Transitional/Emerging Markets

In this type of market, informal institutions have a relatively high impact on the implementation and functionality of the formal institutions. This is to a large extent due to influences from localized mindsets and traditional value systems. These markets constitute high-risk investment climates featuring more or less unstable political regimes generally characterized as low-trust societies due to widespread corruption and nepotism. High economic growth rates derive from a combination of factor cost advantages and investment-driven rationales partially induced by various economic zones established to attract mainly foreign companies and general inflows of foreign direct investments.

The role of the state is somewhere between a liberal and collaborative market economy. The state can best be characterized as developmental in that it not only regulates but also designs economic policies. Countries in this category of markets fall into two main groups. The first consists of the biggest economies; Brazil, Russia, India, and China – the so-called BRIC countries. The other category is mainly found in Eastern Europe, Latin America, Africa, and most of Asia. About 85% of the world's population live in a transitional/emerging market, but collectively contribute about one-third of global gross domestic product (Carney & Witt, 2015; Peng & Meyer, 2019).

“Bottom of the Pyramid” Markets

BOP markets are characterized by an absence of formal institutions to govern rules and regulations and where the impact of the state is almost nonexisting. Informal institutions dominate this type of market and include locally sanctioned norms of behavior embedded in the traditional culture and value systems and providing the basic elements for localized mindsets. The people that live in these markets have no or very limited education and do not hold any assets. The economies have no basic infrastructure and are outside conventional distribution networks and transportation links. They have no access to international capital markets and communication channels, and people generally subsist on less than US$4 a day or U$1.692 a year (Peng & Meyer, 2019).

BOP markets are scattered pocket-wise throughout the world, mostly in countries outside the West, for example, in parts of Latin America, Africa, India, China, and Southeast Asia. These markets are beyond the scope of this study and thus are not discussed in further detail.

Multinational organizations may have to operate to varying degrees across these three rather diverse types of markets depending obviously on the global strategy approach adopted by governance echelons of the company. So, organizations may have to navigate across different economic market contexts characterized by vastly different institutional frames, cultural specificities, and value systems that will affect the local contexts in which company employees act on behalf of the organization. Altogether, this forms the global business environment a multinational organization must relate to as it rolls out its business practices internationally and adds to the complexity of things to consider as a high-level organizational decision-maker.

![]()

Chapter 2

Context and Organizational Change

When attempting to analyze organizational sensitivity to a changing context, it becomes important to consider how to conceptualize the context. Child (2009) points to the danger that the term “context” can mean all things to all people especially if we analyze contextual issues through the lenses of different disciplines, such as business studies, psychology, or anthropology.

In business studies, including international business, the impact of context on individual and organizational behavior is not sufficiently recognized and appreciated by business scholars. This is the case in international management and global organizational studies (Whetten, 2009). Much of the research in management is susceptible to an attribution error. Ross (1977) maintained that there is a tendency to overemphasize dispositional causes of behavior at the expense of situational causes. He argues that we lack a refined language to express context with a good taxonomy of specific situations (Ross, 1977). It has been suggested that explanatory reductionism plays a role here as researchers seek causal explanations at a lower rather than higher level of analysis (Hackman, 2003). The main discussion in business studies is that context means either everything or nothing (context-free research). The context-free proposition came under heavy critique when indigenous management studies appeared in the mid-2000s (Tsui, 2006). So, on the one hand, context is important, and on the other hand, we need to clarify what context is.

Most research on context focuses on organizational context. As one of the first, Rousseau (1978) noted that the organizational context is an important determinant of attitudes and behaviors among individual employees. He defined context as the set of circumstances or facts surrounding an event that can refer to characteristics of the organizational setting, of the individual or his or her role in the organization, and of any other environmental factor that may shape responses. Contextual variables include characteristics of the task environments, such as task identity, task significance, autonomy, de...