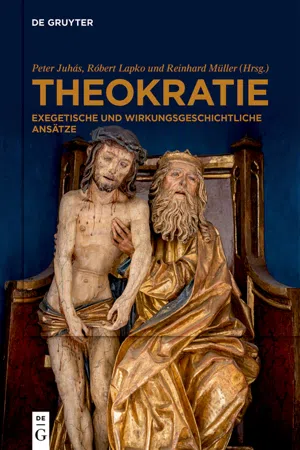

Theokratie

Exegetische und wirkungsgeschichtliche Ansätze

- 316 Seiten

- German

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

Über dieses Buch

Der Sammelband erhellt verschiedene Aspekte von Theokratie und zeichnet ein komplexes Bild des religions- und sozialgeschichtlichen Phänomens, das hinter dem Begriff steht. Das Problemfeld wird anhand jüdisch-christlicher Quellen bearbeitet. Der Band ist als Sammlung von spezialisierten Studien zu zentralen Topoi biblischer Texte angelegt, die mit theokratischen Konzepten zusammenhängen.

Die Beiträge gelten einzelnen Büchern oder kleineren Texteinheiten des Alten und Neuen Testaments, die für das Thema einschlägig sind, sowie exemplarischen Zusammenhängen aus der Umwelt des Alten und Neuen Testaments. Die Leitfragen, die den Untersuchungen zugrunde liegen, betreffen die Rolle der anderen Götter, des Königs, des Priesters und des Messias sowie ihr Verhältnis zueinander und zu Gott in verschiedenen Vorstellungen über die "Gottesherrschaft".

Die Beiträge bieten somit exemplarische Grundlagen, um die spätere Rezeption der theokratisch relevanten Texte kritisch zu bearbeiten. In wirkungsgeschichtlicher Perspektive gilt ein besonderes Interesse theokratischen Aspekten bei russischen religionsphilosophischen Denkern des 19. Jahrhunderts.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Information

Altes und Neues Testament

Israel, the People of God, as Theocracy

1 The Origins of the Term

There is endless variety in the details of the customs and laws which prevail in the world at large. To give but a summary enumeration: some peoples have entrusted the supreme political power to monarchies, others to oligarchies, yet others to the masses. Our lawgiver, however, was attracted by none of these forms of polity, but gave to his constitution the form of what – if a forced expression be permitted – may be termed a “theocracy” placing all sovereignty and authority in the hands of God.1

My kingdom is not from this world.(John 18:36)2

They took the advice of Moses, in whom they all had the greatest confidence, and decided to transfer their right to no mortal man, but to God alone; and without long delay they all promised equally, with one voice, to obey all God’s commands implicitly, and to recognize as law only what he should declare to be such by prophetic revelation.4

The sovereignty of the Jews, then, was held by God alone; and it was the covenant alone which justified them in calling their state God’s kingdom and God their king, and hence in calling the enemies of their state the enemies of God, citizens who aimed at usurping the sovereignty traitors to God, and, finally, their civil laws the laws and commandments of God. Thus in this state civil law and religion, which, as I have shown, lies wholly in obedience to God, were one and the same thing; […] In short, there was no distinction at all between civil law and religion. This was why their state could be called a theocracy – because its citizens were only bound by laws revealed by God.5

Yet all this was based on belief rather than fact; for in fact the Jews retained their sovereignty completely, as will be clear from the manner and method in which their state was governed.6

By these words they obviously abolished the original covenant, transferring their right to consult God and to interpret his decrees to Moses without reserve.7

For as soon as the Jews transferred their right to consult God to Moses, and promised unreservedly to regard him as the divine mouthpiece, they lost all their right completely, and had to accept any successor chosen by Moses as chosen by God.8

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Abkürzungen

- Nachbarkulturen der Bibel

- Altes und Neues Testament

- Wirkungsgeschichte biblischer Texte

- Bibelstellen