![]()

PART ONE

Adaptation in Theory

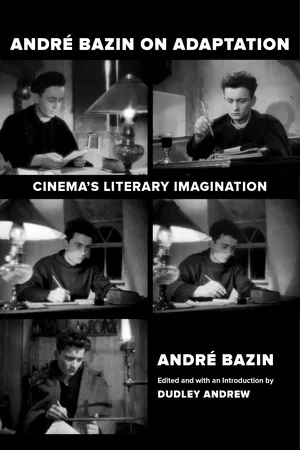

André Bazin’s complex and influential ideas about the adaptation of fiction were elaborated in greatest detail in the two pieces available in English since 1967, one on Robert Bresson’s Journal d’un curé de campagne and the other on so-called impure, or mixed, cinema. Reprinted at the end of this volume, both were conceived during the fifteen-month hiatus, starting in January 1950, that he took from producing daily criticism to recover from tuberculosis. But he had been thinking deeply about adaptation from the outset of his career as a critic, as is emphatically demonstrated by the first selections in this section. His extended early essay on André Malraux’s Espoir manages to honor a film and its versatile auteur, while discussing fundamental concerns about medium specificity (verbal image versus pictorial image), about the distinct audiences that adaptations address (those who have read the novel, those who know about it, and those who just wander into the theater), and about the possibility of an individual style within the constraints of the film industry. All these concerns reappear three years later in the remarkable “Cinema as Digest,” where they are enriched not only by considerations of how the arts and artists have been regarded through the centuries, but also by many examples of adaptation that he had encountered in the meantime. His bold ideas (he invokes the death of the author some twenty years ahead of Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault) follow a strict logic but are carried by ingenious metaphors and analogies.

By 1948 Bazin was considered an expert on this topic, so much so that he was recruited to speak on cinema among the arts at an international congress in Geneva featuring esteemed philosophers, musicians, and art historians. Subsequently, he was asked on occasion to write about adaptation by the editors of literary journals, and in this context he reformulated certain of his cherished beliefs, covering some new ground in the process. Four of these essays directly addressing adaptation are then followed in this section by three others that go at the problem indirectly. For Bazin’s literary sensibility was struck when he ran into such oddities as a full-length film of a famous long poem by Alphonse de Lamartine, and when he reviewed films by two friends and colleagues (Roger Leenhardt and Alexandre Astruc) that, without being concerned with adaptation at all, exhibit, by being novelistic, what I call cinema’s literary imagination.

Part One closes with four intricate essays on knotty “film-literature” problems, occasioned by films largely forgotten today, although one of these, René Clément’s Monsieur Ripois, received considerable attention as a prize winner at Cannes in 1953. Wanting to upgrade the stature of Clément, unfairly denigrated by François Truffaut and others at Cahiers du cinéma, Bazin went all out to think through this film’s ambitions and shortcomings in establishing character subjectivity and interior life via strict cinematic objectivity. Naturally he referred here, as he often did, to Bresson’s Journal d’un curé de campagne, which should be read in tandem with this piece. Even more important, in my view, are the two essays on Mina de Vanghel, a forty-five-minute adaptation from a little-known Stendhal novella. Perhaps because of its awkward length, this film never gained a footing in film societies or among historians, and is currently viewable only in the French archives. Yet Bazin pulls from it profound ideas that open adaptation to new dimensions. For instance, a counterfeit off-screen voice supplements the images until the film seems to overflow the strictures of its brief running time. Like a lawyer for the defense, Bazin eloquently upholds the rights of this voice to undermine the orthodox conception of authorship in adaptation. Even if this case is eccentric, it can serve as a precedent for future scriptwriters.

Bazin’s theoretical position is constituted by striking insights that seem to arise spontaneously within reviews of films like the couple just mentioned. So, take note: such insights leap from many of the reviews that are lodged in Parts Two and Three. Let me point to his appreciation of Billy Wilder’s visual discretion in adapting The Lost Weekend, and to his complex reaction to two films which, for different reasons, were bound to cause a stir in France, Le Rouge et le Noir and Le Blé en herbe. Bazin dedicated two articles to each film. I have placed in this “theoretical” section the two in which his ideas apply to adaptation in general, but the reader may want immediately to read him further on each film, in the articles found in later sections.

![]()

1

Preview: A Postwar Renewal of Novel and Cinema

After Jean Delannoy’s La Symphonie pastorale, starring Michèle Morgan and based on André Gide’s novella, there is now talk of a Princesse de Clèves by Jean Cocteau and a Candide adapted from Voltaire by Jacques Prévert, to be filmed by Marcel Carné. The latest adaptations of Dostoevsky have already provided some sense of this peculiar tendency to prefer adaptations of canonic literary works to original screenplays. Let’s await the outcome.

Yet it might be of interest to observe that in America, all the big productions are adapted from best-selling novels: The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men, Tobacco Road, For Whom the Bell Tolls—these are just the titles best known to the French public. The same holds true, incidentally, for successful Broadway plays.

There is nothing new, of course, in adapting novels to films, but adaptations typically took some liberties with the source. Mostly this consisted in using the subject matter rather than translating for the screen a long narrative, its style included. And that is what today’s best American films seem to do, tending to double the literary work with an equivalent cinematographic one by preserving the complexity and subtlety of the novelist’s art. Will they have succeeded? Soon we will surely find out.

Roman et cinéma

Le Parisien libéré, no. 612, August 2, 1946

Écrits complets, 144

![]()

2

André Malraux, Espoir, or Style in Cinema

A film critic ought to have a lot of trouble with his epithets. His literary counterpart is not required to account for the output of all novels. Literary classifications and hierarchies are relatively well established, and the literary chronicler deliberately ignores much of what is written, including second-rate detective stories, sentimental soap operas for the regional daily, and adventure novels sold at train stations. Nothing forces him to read these, because his public doesn’t. A man of culture, he assumes a cultivated reader. More or less well stratified, a film critic works for a public that, in its vast majority, has no cinematographic culture whatsoever, for whom a film by a Jean Renoir or a Couzinet1 is simply the movies. Let’s imagine that Mr. Jean Blanzat2 must review five or six novels of the Madame Delly or Jean de La Hire variety weekly;3 a work by Pierre Benoît or Henry Bordeaux every two or three months;4 and a novel by Malraux, Faulkner, Gide, or Martin du Gard no more than once or twice a year: in what style, and with what words, would he venture to address these last works? The film critic, by contrast, is constantly impugned for an imaginary bad faith merely for attempting to remain vigilant and tirelessly issue verdicts on the films he sees, judgments that the literary critic would not even deign to formulate were he to read novels of the same quality. Let me make myself absolutely clear: I am in no way speaking ill of cinema. I even think that film production in its entirety is ultimately superior to the entirety of literary production, but ancient academic habits, an intellectualist culture the critic respects and perpetuates, is exactly what diverts us from considering literature in its entirety. In literary geography, there are only great heights. A critic with a taste for sociology occasionally ventures into the vast, unexplored plains where 95% of those like us live. It’s quite rare that the aesthetician deigns to follow him there.

This long preamble may not have been necessary. It does, however, make it easier for me to discuss Malraux’s film. The reader must understand that everything that follows here describes the artistic heights of a great literary work. I kindly ask the reader to forget the standard range of epithets we are at times weak enough to deploy to simply describe the films that didn’t bore us. The work I would like to discuss inhabits a realm that the world’s cinema reaches less than once in a hundred times.

Many previous reviews that have appeared rightly have emphasized the relationship between the book and the film; coming somewhat late, I can do little more than repeat their evaluations of the work’s substance, its intrinsic value as well as of the rerelease that has made it so current.5 Espoir is a work of such quality, however, that it can stand up to close scrutiny. I thus accept the nearly unanimous response of the press to the film’s release at the Max Linder and limit myself to a few remarks on stylistics, which, in my opinion, ought to be developed much further.

It is no accident that Malraux is the contemporary writer who has best written about cinema: there are deep affinities between his style and the language of the screen. He was the first, I believe, to comment on the role of ellipsis in film, and on the ever more frequent use of this figure in the contemporary novel (his own, in particular). However, there is a confusion in that affinity that we might not have suspected a priori, but which becomes apparent with time. In Malraux’s film, it may be that the ellipsis is no less effective or has any less aesthetic impact than in the book, but it penetrates the image only by doing violence to it. This unexpected resistance of cinematic expression to the transcription of an already elliptical book can, I think, shed light on an important point with regard to literary and cinematographic stylistics.

In the pages of this very journal, Claude-Edmonde Magny thoroughly analyzed the meaning of an ellipsis in contemporary literature: it destroys the possibility of meaning and introduces a void between objects and moments. The metaphysics of the ellipsis is not the same in Malraux, Camus, and Faulkner, of course. What all these contemporary novelists have in common, however, is that they want to use ellipsis to introduce temporal and spatial discontinuity in a story in such a way as to prevent us from automatically organizing reality on the basis of a particular logic of appearances, preventing us from giving it meaning. More than any other, Malraux’s aesthetic develops through his choice of discontinuous moments. The story line is interrupted intentionally. Only a few broken links are scattered over the course of an action and confound even an attentive reader’s efforts to reconstruct it fully.

Cinema, however, appears unable to tolerate discontinuity. For all its structure, fragmented into shots, the cinematic narrative tends increasingly to shield us from breaks. “Découpage,” the professionals’ ...