![]()

CHAPTER 1

Emergence of the Disruptive Environmental Justice Movement

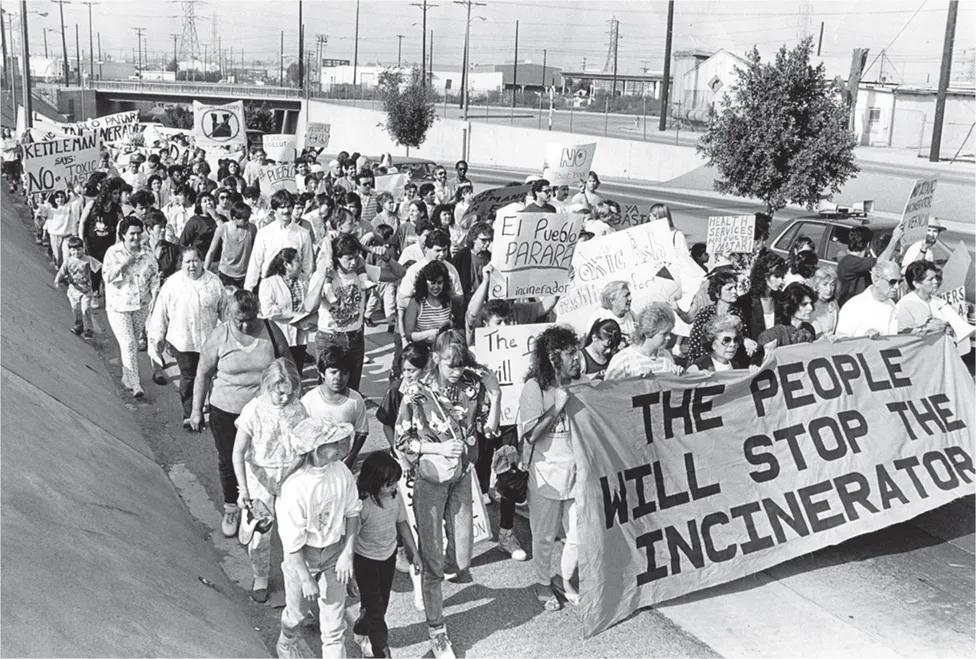

On November 12, 1988, activists from fourteen California communities traveled to East Los Angeles to march with residents who sought to block the construction of two large-scale commercial incinerators. The incinerators would be the first of their kind in the state to burn hazardous waste. Growing resistance to living near landfills meant industry and government officials had difficulty siting new ones to manage growing waste production.1 As a result, proposals to build incinerators skyrocketed; the East Los Angeles incinerators were part of a wave of at least thirty-four proposed in the state during the early to mid-1980s.2 The waste industry hoped to avoid the opposition that plagued landfills by depicting incinerators as a new technology that was clean and safe. Some industry representatives even claimed that incinerators could make waste disappear. Industry proponents also argued that incinerators could help supply electricity to energy-hungry urban areas—a compelling argument after the 1970s energy crises. Accordingly, state and federal governments favored the incinerator industry with tax breaks and guaranteed electricity sales.3 Activists, however, contested industry claims that such facilities could effectively generate significant amounts of electricity. And, they pointed out, waste incineration does not make waste disappear. It converts it into toxic ash and health-threatening air emissions, such as dioxins and furans, which can cause hormonal changes, reproductive and immunological problems, and cancer.4

FIGURE 5. Residents and supporters marching in protest against proposed Vernon hazardous waste incinerators, November 12, 1988. Photo by Mike Sergieff, Herald Examiner Collection, Los Angeles Public Library.

The East Los Angeles incinerators were to be sited in Vernon, a small industrial town that bordered the low-income, predominantly Latinx residential areas of Maywood, Bell, Boyle Heights, and East Los Angeles, in general.5 They would be built and run by California Thermal Treatment Systems, whose parent company, Security Environmental, had been repeatedly cited for violating pollution rules at its other nearby sites in Long Beach and Garden Grove, cities that were in transition from majority white to majority people of color populations during the 1980s. Although the new incinerators were projected to create nineteen thousand tons of toxic ash, dust, and other hazardous waste per year, adding a significant new source of air pollution to the most polluted air basin in the country, regulators green-lighted the project without even requiring that an environmental impact report first be conducted. As community members learned more about the project, their opposition grew. But they faced an uphill battle. As their lawyer remembers, “Before opponents knew what hit them, the thirty-day statute of limitations under CEQA [California Environmental Quality Act] had expired. With construction permits already issued by the South Coast Air Quality Management District and EPA [Environmental Protection Agency], and with the support of the California Department of Health Services, and the City of Vernon assured, the project looked unstoppable.”6 Nonetheless, angry residents and their supporters forcefully voiced their opposition. As one participant recalls:

There was a series of meetings that the government did, as part of their process for rubberstamping this hazardous waste incinerator proposal. . . . Then they announced the hearing. . . . They thought a lot of people weren’t going to show up, after all, “It’s East LA.” It was awesome because 600 people showed up. . . . So the place is packed . . . hundreds marched in. It was awesome. And again, just a massive crowd. The hearing’s in English, and the crowd starts asking for translation. They say no. So, the entire crowd is on its feet, at the top of their lungs for probably 45 minutes: “En español, en español!” It was mass civil disobedience, right? You are not going to have this hearing in English in East LA! . . . Then a state official . . . announced, “We’d really like to be able to translate this for you.” Of course, they’re saying this in English, “But state law prohibits us from translating this meeting.”

The crowd is going nuts, right? Young people unfurled a banner behind the stage, and the place is rocking. And then mysteriously after a really long time, half hour, 45 minutes, the law must have changed, because the state official gets up and says, “Well, I guess we can translate, but we don’t have anybody who could do that.” And so, a young Latina with Greenpeace, she offered to go translate. So, the hearing starts. But moments later, the fire department curiously showed up and announced that half the crowd had to leave. And the massive crowd is on its feet chanting in English and Spanish, “Rent the Coliseum, rent the Coliseum!” And nobody would leave. . . . They stopped the hearing and said they would have to reschedule it in a bigger place. So, it was a big victory. And then the next hearing, as I recall, there was like 1,000 people.

Residents, led by Las Madres del Este de Los Angeles (Mothers of East Los Angeles), built support to block the construction of the incinerators through community organizing, lawsuits, and protests. They built partnerships with politicians, nonprofits, and community groups near and far, including other California grassroots environmental justice activists; on the November day in 1988 when community groups around the state came to march with them, the visiting activists were mostly residents of other low-income communities and communities of color who were fighting off waste threats of their own. The tone of the day was boisterous, in keeping with a campaign that had already extended for years and sometimes spilled over into rowdy and disruptive activism. As one participant remembers:

One of the things people were learning . . . was that the government is totally in bed with the polluters, and that if you follow their way of doing it and, you know, “behave,” [laughter] you will lose. . . . When the march started, we didn’t have permits, we just poured into the street. And the rally, after the mile-long march or whatever it was, in front of the proposed site on Bandini Boulevard, we didn’t rally on the sidewalk. It was smack in the middle of Bandini Boulevard. That was really intentional. It was to up the spirit of the people and show defiance, that people aren’t going to take this lying down, literally.

Ultimately, the anti-incinerator campaign in Vernon was successful, and it became a central event in the coalescence of disparate groups into the statewide environmental justice movement. The company proposing to build the incinerators abandoned the project in 1991 after an unfavorable ruling in court and unceasing local opposition that led key political leaders, including Tom Bradley, the first Black mayor of Los Angeles, to withdraw their support.

While the campaign started with local Latinx residents and their political representatives, it eventually pulled in a multiracial group of people and organizations from across the state. When the network of people from places facing similar proposals came to East Los Angeles in November 1988, they gathered at the Santa Isabel Church in East LA to meet one another and march together. The next day, activists in Northern California got together in the San Francisco Bay Area town of Martinez for the same purpose. These back-to-back gatherings helped create the first statewide, grassroots alliance to formally link communities facing environmental justice threats: California Communities Against Toxics (CCAT).7

EMERGENCE OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE MOVEMENT

CCAT helped connect and provide support for communities across the state, but by the time it was created in 1988, California activists had already been pursuing overlapping antitoxics and environmental justice campaigns for over a decade. Some of these are well known in certain activist circles. One such fight was the successful campaign against the LANCER waste incinerators. The first of three incinerators proposed under this project was to be built in South Central Los Angeles. Robin Cannon, Charlotte Bullock, and the predominantly Black Concerned Citizens of South Central Los Angeles (CCSCLA) organized against the incinerator beginning in 1985.8 CCSCLA’s efforts, and those of the others opposed to the South Central incinerator, prevented a new source of air pollution from being added to what was then the most heavily polluted air basin in the country. These efforts also prevented the associated, localized negative health impacts of that air pollution, which would have been disproportionately born by the largely Black residents of South-Central.

Farther inland from East Los Angeles, another high-profile California case took place at the Stringfellow Acid Pits and the town below; resistance to the acid pits came from the predominantly white working-class residents of Glen Avon. These residents had been complaining about fumes from the liquid hazardous waste storage site above their homes since 1963. In 1969, some of these residents called the police because fumes were so thick it was difficult to breathe, and liquid hazardous waste was flowing down from the Stringfellow Acid Pits into the city streets. In 1978, in anticipation of heavy rains that might breach the dam holding back the liquid hazardous waste, the Santa Ana Regional Water Quality Control Board authorized a “controlled release” into the ravine below. The liquid hazardous waste combined with floodwaters to flow down the ravine and onto the roads and sidewalks of Glen Avon, where children played in the foam it created. Residents organized into the neighborhood group Mothers of Glen Avon, later Concerned Neighbors in Action. They worked for years to address the problems stemming from the site. Activists engaged in a protracted campaign to clean up the site that continues to this day.9

Other toxics threats across the state—threats to both communities of color and low-income majority-white communities—also catalyzed local antitoxics and proto-environmental justice residents’ groups and NGOs. In the small San Joaquin Valley town of McFarland, predominantly working-class Latinx residents spent a decade fighting for redress for a childhood cancer cluster discovered in the early 1980s that may have been caused by the heavy use of carcinogenic pesticides in the nearby fields. The town’s children developed a variety of cancers, such as neuroblastoma and lymphatic cancer, and between 1981 and 1983 residents also suffered through heightened rates of birth defects, miscarriages, and fetal and infant deaths.10

In the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1980s, the then predominantly white Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition organized against the Silicon Valley semiconductor factories. The factories were exposing their workers, many Asian Pacific American, to hazardous chemicals. The factories also polluted local groundwater. In December 1981, it was discovered that a well that provided the drinking water to 16,500 homes in South San Jose—an area predominantly inhabited by people of color—was contaminated with trichloroethane (TCA), a solvent used to remove grease from microchips and printed circuit boards as part of the semiconductor manufacturing process.11 Officials estimated that fourteen thousand gallons of TCA and another forty-four thousand gallons of other toxic waste had been leaking from an underground storage tank for at least a year and a half.

Also in the San Francisco Bay Area, a multiracial array of activist groups—the predominantly Black West County Toxics Coalition, the then predominantly white Citizens for a Better Environment (later, the multiracial Communities for a Better Environment), and the predominantly white National Toxics Coalition—all organized residents in the 1980s to oppose Chevron’s day-to-day refinery operations, which created pollution and industrial accidents that impacted a predominantly Black area of Richmond. Black resident and activist Henry Clark recalls what it was like to live in Richmond at that time:

We lived next to the oil refinery, next to the Chevron Refinery. Next to it in the sense that the refinery is located on the mountain range, and in between the refinery and our house there’s a field which I understand is owned by Chevron. So as you leave from the refinery on the hills and look there to the first streets in the residential area, the first house is our house. So that’s why we say that North Richmond is on the front line of the chemical assault because whenever there was any fires and explosions, that would rock the houses like they were caught in an earthquake. . . . I would be hit first and people on that street, because we were the first street there. . . . I can remember clearly waking up many mornings and finding the leaves on the tree burnt crisp overnight from chemical exposure, or going outside and the air would be so foul that you would literally have to grab your nose and try to not breath [sic] the air and go back in the house and wait until it was cleared up. Those types of situations, you know, were a common experience.12

The geographically separate but roughly contemporaneous activist campaigns in McFarland, Glen Avon, Silicon Valley, Kettleman City, Vernon, South Central Los Angeles, and Richmond have been well documented individually (though they are rarely written into a single narrative of California activist history). Other antitoxics and environmental justice campaigns of the 1980s and 1990s that took place both before and after the formation of CCAT are less well documented and risk being lost to history altogether. For example, in the open desert above Los Angeles County, activists led by white resident “Stormy” Williams prevented the construction of a hazardous waste landfill in Rosamond. And in 1989, after years of organizing, others closed the hazardous waste landfill in the coastal town of Casmalia, where landfill managers had been spraying liquid hazardous waste onto the hillsides in order to speed evaporation, sending overpowering toxic fumes into the local school.13

There was also a slew of campaigns from Indigenous organizers that tied together earlier activism with the emerging environmental justice movement. In the late 1970s, Latinx and Chemehuevi activist Alfredo Figueroa worked to defeat the proposed Sundesert Nuclear Plant. It was to be built in the Mojave Desert, part of the greater US Southwest that has long been burdened with toxins from the long-term impacts of the nuclear life cycle. Southwest deserts have been used for everything from uranium mining to nuclear bomb testing and are consistently proposed for various nuclear waste storage plans. Other Indigenous activists in the area conducted different campaigns, fighting to prevent the dumping of sewage sludge on land owned by the Torres Martinez Desert Cahuilla Indians and working against numerous other proposals to site toxic infrastructure on reservations—proposals that spiked in the late 1980s and early 1990s.14 In the 1990s, other Indigenous and white activists worked to prevent the construction of a nuclear waste landfill in the Mojave Desert’...