![]()

Chapter 1

Differentiation: An Overview

Note that differentiation relates more to addressing students' different phases of learning from novice to capable to proficient rather than merely providing different activities to different (groups of) students.

—John Hattie, Visible Learning for Teachers

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Differentiation of instruction is often misconstrued. It would be handy to represent differentiation as simply instructional decision making through which a teacher creates varied learning options to address students' diverse readiness levels, interests, and learning preferences. Although that approach is attractive because it simplifies teacher thinking, administrator feedback, and professional development design, it is ineffective and potentially dangerous. To see differentiation as an isolated element reduces teaching to a series of disconnected components that function effectively apart from the whole. The more difficult and elegant truth is that effective teaching is a system composed of interdependent elements. As with all systems, each part is enhanced when others are enhanced, and each part is diminished when any part is weakened.

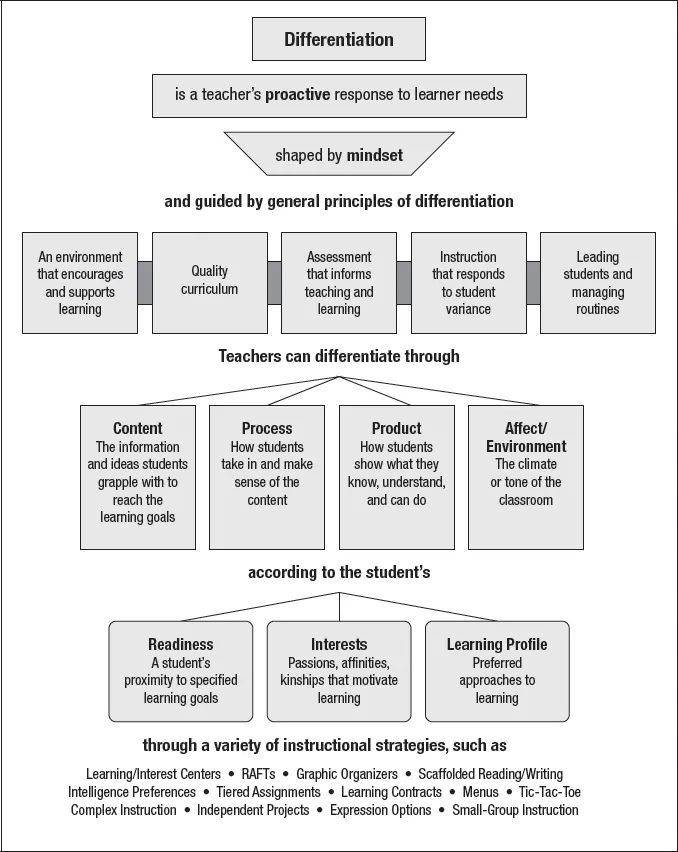

Robust teaching links five classroom elements so that each one flows from, feeds, and enhances the others. Those elements are learning environment, curriculum, assessment, instruction, and classroom leadership and management (Tomlinson & Moon, 2013). This chapter provides a brief overview of each of the elements as they relate to one another and to differentiation. Understanding the mutuality that excellent teachers strive to achieve among the elements also establishes a clear context for an extended discussion of the powerful role of assessment in differentiation. Figure 1.1 provides a flowchart or concept map of the key elements of differentiation.

Figure 1.1 Key Elements of Effective Differentiated Instruction

Learning Environment and Differentiation

Learning environment refers to both the physical and the affective climate in the classroom. It is the "weather" that affects everything that happens there. Few students enter a classroom at the outset of a new school year asking, "What can you teach me about grammar?" (or the periodic table or cursive writing or planets). Rather, they come with an overriding question: "How is it going to be for me in this place?" The nature of the learning environment for that young person will, in large measure, answer that question.

Regardless of the age of the learners, they ask questions such as these (Tomlinson, 2003):

- Will I be affirmed in this place? (Will people accept me here—find me acceptable? Will I be safe here as I am? Will people listen to me and hear me? Will someone know how I'm doing and how I'm feeling? Will they care? Will people value my interests and dreams? Will my perspectives be honored and acted upon? Will people here believe in me and in my capacity to succeed?)

- Can I make a contribution in this place? (Will I make a positive difference in the work that goes on here? Do I bring unique and important abilities to the work we need to do? Can I help others and the class as a whole do better work and accomplish more important things than if I weren't here? Will I feel connected to others through common goals?)

- Will I grow in power here? (Is what I learn going to be useful to me now as well as later? Will I learn to make choices that contribute to my success? Will I understand how this place operates and what is expected of me here? Will I know what quality looks like and how to achieve it? Is there dependable support here for my journey?)

- Do I see purpose in what we do here? (Do I understand what I'm asked to learn? Will I see meaning and significance in what we do? Will what we learn reflect me and my world? Will the work engage and absorb me?)

- Will I be stretched and challenged in this place? (Will the work complement my abilities? Will it call on me to work hard and to work smart? Will I be increasingly accountable for my own growth and contribution to the growth of others? Will I regularly achieve here things I initially think are out of my reach?)

Many years ago, Hiam Ginott (1972) argued that the teacher is the weather-maker in the classroom, with the teacher's response to every classroom situation being the determining factor in whether a child is inspired or tortured, humanized or dehumanized, hurt or healed. In fact, research has repeatedly indicated that a teacher's emotional connection with a student is a potent contributor to academic growth (Allen, Gregory, Mikami, Hamre, & Pianta, 2012; Hattie, 2009). That connection enables the student to trust that the teacher is a dependable partner in achievement.

In a differentiated classroom, the teacher's aim is to make the classroom work for each student who is obliged to spend time there. Thus the teacher is attuned to the students' various needs and responds to ensure that the needs are met. Various scholars (Berger, 2003; Dweck, 2008; Hattie, 2012b; Tomlinson, 2003) have noted that the teacher's response to student needs includes the following:

- Belief—Confidence in the students' capacity to succeed through hard work and support—what Dweck (2008) calls a "growth mindset"; the conviction that it is the students' committed work rather than heredity or home environment that will have the greatest impact on their success.

- Invitation—Respect for the students, who they are, and who they might become; a desire to know the students well in order to teach them well; awareness of what makes each student unique, including strengths and weaknesses; time to talk with and listen to the students; a message that the classroom belongs to the students, too; evidence that the students are needed for the classroom to be as effective as it should be.

- Investment—Working hard to make the classroom work for the students and to reflect the strengths of the students in it; enjoyment in thinking about the classroom, the students, and the shared work; satisfaction in finding new ways to help students grow; determination to do whatever it takes to ensure the growth of each student.

- Opportunity—Important, worthy, and daunting things for the students to do; a sense of new possibilities; a sense of partnership; roles that contribute to the success of the class and to the growth of the students; expectation of and coaching for quality work.

- Persistence—An ethic of continual growth; no finish line in learning for teacher or students; no excuses; figuring out what works best to support success; the message that there's always another way to approach learning.

- Reflection—Watching and listening to students carefully; using observations and information to make sure each student has consistent opportunity to learn and succeed; working to see the world through the student's eyes; asking what's working and what can work better.

The teacher has the opportunity to issue an irresistible invitation to learn. Such an invitation has three hallmarks: (1) unerring respect for each student's value, ability, and responsibility; (2) unflagging optimism that every student has the untapped capacity to learn what is being taught; and (3) active and visible support for student success (Hattie, 2012b; Skinner, Furrer, Marchand, & Kindermann, 2008). When a teacher exhibits these hallmarks, students feel the teacher is trustworthy—will be a reliable partner in the difficult and risky work of real learning. That feeling enables the teacher to forge connections with students as individuals.

These teacher-student connections provide opportunity for a teacher to know students in a more realistic and multidimensional way than would be the case without such mutual trust. They create a foundation for addressing issues and problems in a positive and productive way. They attend to the human need to know and be known. Teacher-student connections also pave the way for the teacher to build a collection of disparate individuals into a team with a common cause—maximum academic growth for each member of the group. In such classrooms, students work together and display the characteristics of an effective team. They learn how to collaborate. They use their complementary skills to enable each member to capitalize on strengths and minimize weaknesses. They learn responsibility for themselves, for one another, and for class processes and routines.

The way in which students experience the classroom learning environment profoundly shapes how they experience learning. Nonetheless, the other classroom elements also profoundly affect the nature of the learning environment. For example, if the curriculum is flat, uninspired, or seems to be out of reach or detached from a student's world, that student's need for challenge, purpose, and power goes unmet and the learning environment suffers. If assessment feels punitive and fails to provide a student with information about how to succeed with important goals, the environment feels uncertain because challenge and support are out of balance. If instruction is not responsive to student needs in terms of readiness, interest, and approach to learning, the environment does not feel safe and the student does not feel known, valued, appreciated, or heard. Finally, if classroom leadership and management suggests a lack of trust in students and is either rigid or ill structured, the learning process is impaired and, once again, the environment is marred. Every element in the classroom system touches every other element in ways that build up or diminish those elements and classroom effectiveness as a whole.

Curriculum and Differentiation

One way of envisioning curriculum is to think of it as what teachers plan to teach—and what they want students to learn. The more difficult question involves delineating the characteristics of quality curriculum—in other words, the nature of what we should teach and what we should ask our students to learn. Although that question has no single answer, ample evidence (e.g., National Research Council, 2000; Sousa & Tomlinson, 2011; Tomlinson & McTighe, 2006; Wiggins & McTighe, 1998) suggests that curriculum should, at the very least, have three fundamental attributes. First, it should have clear goals for what students should know, understand, and be able to do as the result of any segment of learning. Second, it should result in student understanding of important content (versus largely rote memory of content). Third, it should engage students in the process of learning.

Goal Clarity

Although nearly all teachers can report what they will "cover" in a lesson or unit and what their students will do in the lesson or unit, few can specify precisely what students should know, understand, and be able to do as a result of participating in those segments of learning. Without precision in what we've called KUDs (what we want students to know, understand, and be able to do), several predictable and costly problems arise. Because learning destinations are ambiguous, instruction drifts. In addition, students are unclear about what really matters in content and spend a great deal of time trying to figure out what teachers will ask on a test rather than focusing on how ideas work and how to use them. Third, assessment and instruction lack symmetry or congruence. What teachers talk about in class, what students do, and how they are asked to demonstrate what they've learned likely have some overlap, but not a hand-in-glove match.

From the standpoint of differentiation, lack of clarity about KUDs makes it difficult, if not impossible, to differentiate effectively. A common approach occurs when teachers "differentiate" by assigning less work to students who struggle with content and more work to students who grasp it readily. But it is neither useful to do less of what you don't understand nor more of what you already know. Effective differentiation is most likely to occur when a teacher is (1) clear about a student's status with specified KUDs, (2) able to plan to move students forward with knowledge and skill once they have mastered required sequences, and (3) able to "teach backward" to help students who lack essential knowledge and skill achieve mastery, even while moving the class ahead. In differentiating understandings, teachers are likely to be most effective when they have all students work with the same essential understandings but at varied levels of complexity and with different scaffolding based on the students' current points of development. These more defensible approaches to differentiation are unavailable, however, without clear KUDs.

Focus on Understanding

If we intend for students to be able to use what they "learn," memorization is an unreliable method to accomplish that goal. Students fail to remember much of what they try to drill into their brains by rote recall, even in the short term. Further, they can't apply, transfer, or create with "knowledge" they don't understand—even if they do recall it (National Research Council, 2000; Sousa & Tomlinson, 2011; Wiggins & McTighe, 1998). Understanding requires students to learn, make sense of, and use content. It also suggests that the U in KUD is pivotal. Making understanding central in curriculum calls on teachers themselves to be aware of what makes their content powerful in the lives of people who work with it, how the content is organized to make meaning, and how it can connect with the lives and experiences of their students. It also calls on a teacher to create sense-making tasks for students in which they use important knowledge and skills to explore, apply, extend, and create with essential understandings.

In terms of differentiation, creating understanding-focused curriculum asks teachers to realize that students will approach understanding at varied levels of sophistication, will need different support systems to increase their current level of understanding of any principle, and will need a range of analogies or applications to connect the understanding with their own life experiences. In terms of assessment, an understanding-focused curriculum suggests that pre-assessments, formative (ongoing) assessments, and summative assessments will center on student understanding at least as vigorously—and generally more so—than on knowledge and skill. In fact, assessments that help students connect knowledge, understanding, and skill will be particularly potent in the learning process.

Engagement

There is a clear link, of course, between understanding and engagement. It's difficult to invest over time in content and ideas that feel inaccessible or estranged from personal experience. Engagement in the classroom results when a student's attention is attracted to an idea or a task and is held there because the idea or task seems worthwhile. Students become engrossed because the task is enjoyable, or because it seems to provide them with the power of competence or autonomy, or because it links with an experience, interest, or talent that is significant to them, or because it is at the right level of challenge to stimulate rather than frustrate or bore them—or likely because of a combination of these conditions. When students are engaged, they are more likely to concentrate, remain absorbed with a task, persist in the face of difficulty, experience satisfaction, and feel pride in what they do. Conversely, lack of engagement leads to inattention, giving up, withdrawal, boredom, and frustration, anger, or self-blame (Skinner et al., 2008). Curriculum that promotes understanding is engaging in a way that drill and rote memory seldom are, and conversely, curriculum that is engaging causes students to persist in achieving understanding. Phil Schlechty (1997) says that the first job of schools (and the second and the third …) is to produce curriculum that is so engaging for students that they keep working even when the going gets tough, and that results in a sense of satisfaction and even delight when they accomplish what the work asks of them.

In terms of differentiation, tasks will sometimes need to be at different degrees of difficulty or linked to different experiences, interests, and talents in order to engage a broad range of learners. In terms of assessment, it's useful to realize that students are less likely to invest effort in assessments that they see as detached from their lives and experiences, or that are at a level of challenge that is out of sync with their current point of development.

"Teaching Up"

In addition to goal clarity, a focus on understanding, and the ability to engage students, quality curriculum has one additional characteristic that aligns with a sound philosophy of differentiation: the principle of "teaching up." When designing a differentiated task to address student readiness needs, a teacher must decide on a starting point for planning. Is it best to plan first for the "typical," or "grade-level," student and then differentiate by making some tasks easier? Or perhaps it makes better sense to begin with designing work for students who struggle with particular content and then to enrich the work for students whose proficiency is beyond basic. In fact, a third option is far more powerful on several levels. If teachers routinely began planning student work by developing tasks that would invigorate students who are advanced in a topic or content area and then differentiate by providing scaffolding that enables the range of less advanced learners to work successfully with the advanced-level task, achievement would be accelerated for many other students. Further, "teaching up" has at its core a connection between curriculum and learning environment. When teachers believe unequivocally in the capacity of their students to succeed through hard work and perseverance, it's natural to provide work that complements the capacity of each student to think, problem solve, and make meaning of important ideas. "Teaching up" communicates clearly that everyone in the class is worthy of the best curriculum the teacher knows how to create. Differentiation makes it possible for a broad range of students to step up to the challenge.

Assessment and Differentiation

If teachers strongly believe in the ability of their content and curriculum to improve students' prospects and lives and in the worth and potential of their students, it fol...